Christopher Jackson

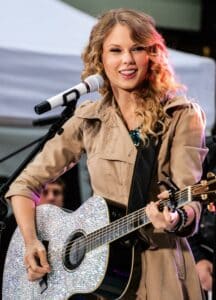

The New Yorker once wrote that Taylor Swift has ‘the pretty, but not aggressively sexy, look of a nineteen-thirties movie siren’. But perhaps most notable is how it has changed over the years: to look at her is to try to gauge what the white skin and essentially kind eyes really do look like when set against all the confusions created by her ubiquity.

To look at her – even on the TV screen – is to look at fame on a scale which is very rarely attained. This is the perennial camouflage of celebrity – all that we think we know about her has come to us second-hand, and it’s misleading because a person is not an aggregation of what has been said about her. A person is an accumulation of raw experience: the camera cannot capture that – it keeps removing us from the lived actual.

On the other hand, Taylor Swift’s success is partly due her ability to communicate through contemporary media. She has become so well-known really due to the authenticity of joy – or at least the authentic search for it. “Happiness isn’t a constant,” she has said. “You get fleeting glimpses. You have to fight for those moments, but they make it all worth it.” The impression one has of Swift is of someone increasingly adept at that search – precisely because she knows that it isn’t only to do with what one attains for oneself but what one can return back into the world.

Swift seems to me to represent some new need – or rather a new way in which an old need has been answered when no other public figure, and especially not our politicians, are able to answer it. At her core is a commitment to kindness, and this, through her songs – but at least as importantly by her deeds – has become catching.

It has created a movement around what some clever people might deride as a cliché. Of course, she swears (“Fuck it, if I can’t have him” she sings on ‘Down Bad’ on her latest album), and issues the occasional diss track – but really her generosity as a performer, as a famous person and as a philanthropist us the leitmotif which runs through all she does.

This anchors her. How many people are actually good at being famous in the way that Taylor Swift is good at it? Very few can accept it with any degree of balance and humility – and it is vanishingly rare to find a sane identity. It was Marilynne Robinson who observed of her friend Barack Obama – one of the few people, along with the tennis-player Roger Federer to seem as comfortable with fame as Swift is – that he showed ‘tremendous alertness as to what the moment may require of him.”

As one watches Swift on her Eras Tour, one senses something similar in play – a hypersensitivity to what her audience needs from her, and a willingness and an ability to supply it. It is a question of an optimistic and accommodating attitude on a scale hard to imagine. “My fans don’t feel like I hold anything back from them. They know whatever I’m going through now, they’ll hear about it on a record someday,” she has explained, but it is more than that – she has embarked on a life which is more relentlessly public than anyone I can think of. Her life is the community she has created through her music.

Consider this quote, in which she shares her experience with her fans: “When I was a little girl I used to read fairy tales. In fairy tales you meet Prince Charming and he’s everything you ever wanted. In fairy tales the bad guy is very easy to spot. The bad guy is always wearing a black cape so you always know who he is. Then you grow up and you realize that Prince Charming is not as easy to find as you thought. You realize the bad guy is not wearing a black cape and he’s not easy to spot; he’s really funny, and he makes you laugh, and he has perfect hair.”

This is a beautifully articulated observation about the distance between fairytale and life, and I think there’s no doubt why she’s making it: it’s because she doesn’t want others to suffer. She cares.

Her work can be seen as a working through of this difficulty – even its dramatization. We enter a world which feels at first insufficiently signed, and we must learn to discover what things are like: art is a way of coming into knowledge about this. Taylor Swift’s songs are about this journey, and she has described with a mining obsession. She is one of those writers who isn’t content to skim her topic; she delves.

Even so her fame has made it difficult to discern what drives her as a songwriter. The course convener for the Taylor Swift course at Basel University Dr Andrew Shields says in our Question of Degree in this issue that many people misunderstand the essential genesis of Swift’s work: ”When I stumbled on ‘Blank Space’, I came to understand that she was writing fiction. Even in songs where you think she may have just sat down and versified her biography, even there, there’s still fictionalisation,” he explains.

Shields argues that we have difficulty in placing Swift, since she comes out of the country milieu but has crossed over into pop. Shields compares her to Adele: “Around the time, I first got into Taylor Swift, I also bought my daughters the albums 21 and 25 by Adele. I took them to the gym and everything about those albums is about excellence. The voice is excellent. The framing of the voice in the mix is superb. Her articulation in the mix is superb. Her articulation is fantastic. She also writes harmonically and melodically richer stuff than Swift does.”

I feel a ‘but’ coming and indeed it does come. “But the lyrics sound like they’re just scribbled down stuff. Adele is working in studios with some of the best people in the world, and that is what makes her successful along with her incredible voice, but apparently they don’t need to have decent lyrics. ‘Hello’, for example, is an incoherent text.”

This, says Shields, is what makes Swift so special: “Swift tells stories: she has characters, and she has wit.” For Shields, Folklore, which landed at the start of the pandemic, is the breakthrough album. “Until that album, I’d find listening to more than an album’s worth at a time a little too much, but there’s more room in Folklore.”

Like Dylan’s ‘Murder Most Foul’, Folklore arrived to console us at a time none of us shall forget: it is part of that historical moment.

When one sees Paul McCartney at the Eras tour, we are reminded that he likely wouldn’t be there if he didn’t think the performer on stage were a songwriter: and of all people he should know. McCartney’s attendance was especially interesting since he is one of the few people alive today who know what this kind of fame is like.

As Swift swung through London, emitting minor earthquakes at the biggest venues in the country, her physical presence in one’s general vicinity wasn’t something possible to ignore even if one were inclined to do so.

The evidence is that Swift is capable of getting to more or less anybody capable of being got to. One is Angelina Giovani, who describes for me the scenes in London at Wembley Stadium. What was it that turned her into a Swiftie? “I am not on original, die hard Swiftie, to be honest,” she replies, though her eyes are shining slightly at the mention of Swift’s name. “I first started paying attention to her when she started re-recording her old albums so she could own them. I thought that was very brave and very smart.

But what really brought her into my radar was the Eras tour. I remember last year, early in the tour it rained through many of the early performances, and she carried on singing her entire track list completely unbothered by it. She did the same in the Brazil, where the heat was insufferable and she managed to keep performing, while visibly struggling with her breathing between songs. I was very impressed by the endurance and commitment.”

This is something which one can easily miss: her professionalism, which is such a fait accompli now that one can easily underestimate the effort which went into its acquisition. Up there onstage during the Eras tour, one can see, behind the theatre of it all, the sheer extent of her determination: a work ethic which again is hard to think of having been matched in pop since McCartney.

We see in the marvellous Peter Jackson film Get Back how for every song that each of the other band members were writing, McCartney was writing ten and it ended up being too much for the rest of the band to cope with. Swift is a little like this, issuing earlier this year not the expected album, but a double album in the shape of The Tortured Poets Department: the impression is of hyperactivity, and an energy going in all directions – into her music videos, and indeed into her every move. She is an advert for superior planning – and for doing things for the right reason.

But predominantly, nowadays it is going into her Eras show, which treats each of her albums as an epoch to be explored and re-enacted. It was the late great Tony Bennett who said in relation to Amy Winehouse that no jazz singer likes to see 90,000 people staring back at her. Swift doesn’t seem to mind that at all.

The author of the best book about Swift is The Secret Critic who speaks to me over email in order to retain his or her anonymity. His book Taylor Swift: The Anatomy of Fame is like no other: a tour de force of literary criticism, which addresses the Swift phenomenon in highly original terms.

The author tells me: “Swift can’t sing like Winehouse – which is no shame, as she was a one-off – but the quote is a reminder that large stadiums are a problem to be solved. The only person really to solve it before Swift was Freddie Mercury – and I occasionally see Swift deploying gestures at the piano which remind me a little of him, tipping her whole body back theatrically. Mercury knew that these arena require exaggerated gestures – and Swift knows this too.”

For the Secret Critic, it is also a question of intimacy: “Mercury also understood that the only way to make the space smaller is to connect intimately with the people in it as he did with his famous ‘Day-dos!” So how does Swift do it? “What’s unique is that she does it through respect, humility, and an earned familiarity.

She couldn’t play these venues if she’d ever put a foot wrong in displaying respect towards her audience; the act simply wouldn’t work if she had ever done that. It is this peculiar bond between her and her audience which enables her to handle these enormous audiences. There has never been anything like this – by comparison, Mercury looks remote from his audience. There was no Queen community in quite the same way that there’s a Swift community.”

For me, the Eras show works partly due to its choreography where Swift accepts a central role while also sharing it with others. Again, in compiling the show she is able to borrow from her own hard work in her music videos, which she has always controlled. Some of these are now on display in the V & A Museum. Kate Bailey, Senior Curator, Theatre & Performance, says: “We are delighted to be able to display a range of iconic looks worn by Taylor Swift at the V&A this summer. Each celebrating a chapter in the artist’s musical journey.”

And what is the idea behind the show? “Taylor Swift’s songs like objects tell stories, often drawing from art, history and literature. We hope this theatrical trail across the museum will inspire curious visitors to discover more about the performer, her creativity and V&A objects.”

These outfits, above all, always make one think, for the simple reason that there is never any doubt that a considerable amount of thought has gone into their creation. It is all of a piece with someone who won’t leave anything to chance. The looks that she has produced each speak to a particular mood; her albums represent self-contained aesthetics, which is part of what makes the Eras tour viable at all. Here is Swift, gloriously rainbow-coloured during her Lover era, cabin chic during Folklore, and suitably red during the Red era.

Angelina Giovani explains that even making her way to the concert was an eye-opening experience: “On my way to the concert I saw how most houses on Wembley Hill had put out signs, renting out their driveways to concert goers so they could park. They were all full, going at about £20 for the afternoon.

Swift is playing at Wembley Stadium eight times this summer, during which the average family will make £160 per parking spot. It is not ground-breaking, but it is not nothing. Her fans travel around in thousands to see the concert, they eat, drink and sleep locally and as far as fans go – they’re not football fans. Their most threatening weapon is glitter, so they are made very welcome.”

She is also eloquent about the greatness of Swift as a live performer: “The concert was electric. I have been to many concerts before, primarily rock bands, but this was quite special. I had never seen such a mix of young and old before at Wembley. The youngest concert goer was no more than five years old and the oldest, in their eighties. I found it very heart-warming to find a common source of joy across generations.

There were 84,449 people on her first day at Wembley, and throughout the 46 song track list that she sings she never sang alone. The people who had purchased seated tickets, did not sit down.” Giovanni brilliantly captures the uniquenesss of live concerts: “There’s something about concerts that makes everyone think they can sing, which is endearing. At times it was hard to distinguish Swift’s voice from the crowd. But you can see her relishing in it. She is so tuned it and plugged into the audience. She kept spotting people who needed help in the standing crowd and pointing them out to the first aid crew.”

This is an important point. If one looks at Swift’s predecessors in the 60s, whether it be The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, they had become famous in order to put distance between themselves and others; Bob Dylan, meanwhile, has sometimes shown a kind of lofty contempt for his audience.

The examples of Swift’s good nature are too numerous to have been faked and it is this which causes such widespread happiness: we haven’t been watching a musical phenomenon sweeping through the country so much as a sort of spiritual force. Swift has given huge amounts to charity – and not done it any showy or self-aggrandising way. We can find the friendship bracelets which are handed out at her concerts kitsch if we want, but the moment we think friendship itself is kitsch, we have become cynical, and the joke may have rebounded on us.

Dr Paul Hokemeyer, an extremely successful psychologist, agrees: ”One of the things I find most valuable about Taylor Swift’s uber celebrity is how it transcends the veneer of social media celebrities such as the Kardashians and rejects the meanness of the Real Housewife franchises. In contrast to these other celebrity phenomena, Taylor Swift sends a message of kindness, inclusion, respect and hope. Her music is uplifting. It celebrates the vulnerability inherent in being human and creates connections through communities of joy and the celebration of love and life.”

This is well-put. As we look at the world of politics at time of writing, the UK for all its problems seems a sort of curious bright spot. We find an unhappy American election where some think a new civil war may be imminent; in France things seem even worse – and, of course, the Russia-Ukraine and Middle East conflicts continue, as do threats to our Western way of life from China, North Korea and Iran. The opportunities for despair appear to be legion.

But Taylor Swift, whether one likes her music or not, is against all that, says Hokemeyer. “As a mental health professional, I find the hunger for such messages indicative of the pernicious impact our current culture of ideological division, violence, patriarchy and ecological destruction is having on the younger generations of humans. They are looking, like Harry Harlow’s monkeys, for love, nurturance, benevolent leadership and comfort in their lives.

When Taylor takes the stage, or is heard over earbuds on the tube, she touches her fans on a deeply emotional level. She models power through vulnerability rather than malignant narcissism. She speaks to her tribe in a way that nourishes their hearts, minds and bodies. She makes them feel important, seen, understood and, most of all, valued in ways that our political, religious, corporate and even family leaders have failed them.”

Giovanni agrees: “You can love or hate Taylor Swift, it doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things. Her music is not everyone’s cup of tea and that’s fair enough. But in the past year, Taylor Swift has done more to help with hunger than governments. Measurably so. In every city she plays, she donates to food banks enough money to keep them running for a whole year. Many roll their eyes, it’s all for show, it’s all to paint a certain picture. But does that matter? Not to the people who are getting regular, hot meals.”

In other words, Swift is now in effect beyond her art – she exists in a realm of willy-nilly cultural significance, exactly as the Beatles did. It was a futile thing to announce that one didn’t much like Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in the 1966, the year of its release. It was what was happening then; it was how the world was. Years, later Sir Martin Amis would write in his 1973 novel The Rachel Papers that: ‘To be against the Beatles is against life.” It is the same with Swift today: she is, whether one likes it or not, part of the life force.

But how exactly has this force come about and what does it say about us? Just as in old footage one sees young girls in a sort of delighted panic at the sight of the Beatles performing ‘She Loves You’, today we see their progeny experiencing similar emotions with Taylor Swift. This is interesting because in the case of The Beatles one assumed that sex might have had something to do with the extent of the obsession; but that doesn’t seem to be the case when it comes to Swift.

So what’s going on here? Hokemeyer tells me: “For time eternal, humans have engaged in celebrity worship and oriented themselves in tribal hierarchies. In the realm of psychology, such patterns of being are known as archetypal. They are accepted as part of the universal human experience and involve behaviours that reoccur consistently over millennia and across cultures.”

In other words, what we are seeing is only the latest manifestation of a tendency as ancient as the hills. Hokemeyer continues: “But while this overall pattern of being remains constant, over time, the objects of our celebrity worship change to reflect the contemporary zeitgeist. In ancient Greece, humans worshiped celebrities such as Aristotle and Socrates. These men provided clarity and comfort in a dangerous and chaotic world through logic, reason and intelligence. Fast forward to modern times when today’s celebrities are human beings who have attained elevated levels of financial success and captured the world’s attention by features of their beings: their talent, their power, their beauty, their wealth.”

So we’ve gone away from celebrating intellect towards worshipping money? It isn’t quite as simple as that, says Hokemeyer: “Today’s celebrities such as Taylor Swift, garner and hold society’s projections of superiority over the banality of human existence while providing transcendental experiences to people longing for connection, joy, comfort. She, through her music and charisma, provides a momentary reprieve from what remains a dangerous and chaotic world while allowing us to organize ourselves like honeybees, under a superior other and in colonies of shared purpose and identity.”

What is remarkable about this is just how universal it appears to be. “What is most interesting about Taylor Swift is how she’s been able to garner uber celebrity amongst a geographically, racially, economically and culturally diverse group of people,” Hokemeyer continues. “In contrast to celebrities of the past whose celebrity has been more limited, Taylor has been able to utilize the power of the internet to unite a humanity suffering from an acute state of division, disconnection, violence and environmental degradation by making her fans feel seen, valued and understood through her music, charisma and the community she’s created.”

When I put all this over email to the Secret Critic, the mystery author agrees but also has more to say: “I would argue that Swift, though she seems to have arrived out of the milieu of pop, and even of American Idol and so on, in fact has more in common with the Sixties songwriters than we sometimes think, and far more than her detractors realise. She isn’t only a live concert experience; there’s a genuine listening experience to be had as well.”

Like Shields, The Secret Critic points to Folklore as a period when her songwriting went to a new level where, notwithstanding some dissent over her new album, it has largely stayed. “From Folklore onwards, you’ll find more complex language – a deeper commitment to character. In my book I have an analysis of the Betty trilogy on Folklore and there are some remarkably telling details and some very clever touches in terms of character: she can do the male character voice, and the two very different female characters.

This is far harder than it looks – and she does it.” These three songs, consisting of ‘Cardigan’, ‘August’ and ‘Betty’ are redolent, says The Secret Critic, of those times. “I think that the pandemic period was an opportunity which she seized in some way. She watched a lot of movies and read a lot of books -and the result was a kind of deepening in her art. I would argue that her best song is ‘Exile’ where there is a depth of feeling about the collaboration with The National which has to do with the odd static urgency of that time. I don’t think we see such depth in her recent collaboration with Post Malone.”

Swift herself is very interesting about her craft. “Throughout all of the changes that have happened in my life, one of the priorities I’ve had is to never change the way I write songs and the reasons I write songs. I write songs to help me understand life a little more. I write songs to get past things that cause me pain. And I write songs because sometimes life makes more sense to me when it’s being sung in a chorus, and when I can write it in a verse.”

Love continues to obsess her – relationships are to her, to paraphrase Larkin, what daffodils were to Wordsworth: “I write a lot of songs about love and I think that’s because to me love seems like this huge complicated thing,” she has said. “But it seems like every once in a while, two people get it figured out, two people get it right.

And so I think the rest of us, we walk around daydreaming about what that might be like. To find that one great love, where all of a sudden everything that seemed to be so complicated, became simple. And everything that used to seem so wrong all of a sudden seemed right because you were with the person who made you feel fearless.”

But does The Secret Critic see The Tortured Poets Department as a weaker album? “I do think it’s a problem which pop stars face, and it’s to do with musical education. Classical composers tend not to become samey because they just have so many musical resources at their disposal.

The same just isn’t the case in popular music – even when you look at McCartney who is just this immensely musical guy. Take ‘All Too Well’ as an example. The chord sequence is essentially, C, A minor, F, G – which is broadly the same chord sequence as ‘Let It Be’. But it’s very simple, and the danger is that when you’re writing according to simple structures, you find there are fewer places to go musically.

As I listen to the latest single ‘Fortnite’ I find myself understanding what The Secret Critic is saying: in ways which are difficult to pinpoint the melody, feels of a piece with Midnights but it lacks the excitement of the inspiration which must have accompanied that album.

Why is this? “I’m not saying it’s a terrible album. But I do think its weakness has been masked somewhat by the ongoing success of the Eras tour. Why does pop music tend to fall off a little? There are a few reasons. One was described by Stephen Sondheim. He pointed out that after a while, muscle memory means that when a composer approaches their instrument their hands, by habit, gravitate back to the same chords.

This habitual element to songwriting can be very damaging and create samey work, as I believe it is beginning to do with Swift. John Updike wrote a famous essay called ‘The Writer in Winter’ where he writes of every sentence ‘bumping up against one you wrote 50 years ago’. Updike lived to a fairly decent age, and his prose was rich. Pop tends to stale quicker as the options for creativity appear to be far fewer.”

But there’s another problem. “The other thing is that pop music is the expression of youth. Now, there are a few exceptions here and there to this – Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen were still breaking ground into their 80s. But they came from folk music which is a more cerebral form. Swift is interesting because in Folklore and Evermore, she has shown that she’s comfortable with this genre so there are places for her to explore as a songwriter. It’s just that both Midnights – and now The Tortured Poets Department – have shown her moving in a more disco beat direction. I don’t think the quality will be sustainable in that line.”

Angelina Giovani disagrees: “My favourite album is by far the most recent one The Tortured Poets Department. It’s quite a departure from her usual style of writing, but it is an immersive experience that is very emotionally charged. All feelings come through very clearly, whether it’s heartbreak, pain, anger, relief, reassignment or juvenile joy. My favourite song of the album is ‘The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived’. I can absolutely see it turned into another short film.”

The Secret Critic responds: “If you listen to that song, even the melody along the line ‘ever lived’ is too similar to the melody to Bad Blood. There’s no way to avoid the fact that she’s likely going to go into an artistic decline, and that once this tour is over, and all the noise has died down, we might well have seen peak Swift.”

But the Secret Critic also has fascinating things to say about the scale of the Swift phenomenon. In The Anatomy of Fame he cites what he calls The Peyton Predicament, which references a football commentator and Swiftie called Jared Peyton. Peyton found himself as the Kansas City stadium where Swift’s latest boyfriend Travis Kelce was playing. He decided to go and find her and filmed his quest on Twitter.

What followed went briefly viral online. Peyton, using his insider’s knowledge of the geography of the stadium managed to get to the end of a tunnel just as Swift went past. “I was fanboying out!” he said on the video he streamed on Twitter, which in itself earned him a certain fleeting celebrity. “The Peyton Predicament speaks to the huge importance in many people’s lives,” says The Secret Critic. “My book seeks to ask the question: Why does he feel the need to do that? What is it about her and what is it about us that means that it has come to this?”

It would be easy to be cynical about this and to consider Payton little better than insane to place such emphasis on saying hello to a fellow mortal being. But Dr. Paul Hokemeyer takes a somewhat different view: “At the most primal level of our being, we all need to feel seen and validated by a superior other. This need is hard-wired into our central nervous system. We come out of the womb completely dependent on another human being to feed, love and comfort us. Without this love, we, like the monkeys in the famous Harry Harlow study, will suffer from profound states of emotional despair and poor physical health outcomes.”

By this reckoning then Payton’s behaviour, far from being a bit mad, is in fact deeply human: “When Taylor Swift not just saw, but also gracefully acknowledged Payton’s presence, his central nervous system lit up like Harrods on Christmas Eve and flooded him with a host of endogenous opioids such as dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin. He was elevated to a state of being, ecstasy actually, that might defy logic, but which is consistent with our basic human need to be validated by a superior other. In the experience, Payton transcended his human frailties and became intoxicated with the elixir of celebrity.”

In The Anatomy of Fame, The Secret Critic goes into the matter in even greater detail and analyses the constituents of this appeal from the philosophical perspective. “I wanted to write a book where at the beginning we see Payton in one way – but by the end we’re brought round to his way of seeing – or at least to understanding it. If someone said to you: ‘Taylor Swift is over there, you might want to go and see her,’ you’d think one set of thoughts. But if I said: ‘Somebody who embodies beauty, creativity, kindness and power’ is over there, you’d say: ‘Well, you should definitely go and talk to her’. But to Peyton that’s exactly what Swift is.”

The book therefore breaks down Swift’s appeal looking at her songwriting, her beauty, and above all her morality. The effect is very profound. We see how Swift has effectively straddled the songwriting of the 1960s and written songs which are close to being standards, while also becoming the premier live performer of our time. She exhibits beauty but also vulnerability. But above all she joins power with a matter-of-fact kindness which never feels affected.

I decide I want to test The Secret Critic’s theory on Angelina Giovanni, who enthuses: “I find it rather impressive that people who work with and for her and don’t seem to have a bad word to say and are always raving about her generosity. Everyone on her team from truck drivers, to back up singers have received life changing bonuses, totalling a whopping $55 million dollars. That’s why I’m rooting for her to be even bigger. I love the fact that it is someone of my generation that has made it so big, so young and is on track to breaking so many musical records previously held by music’s biggest names.”

Of course, there are limits to her power. As the Netflix film Miss Americana shows, her intervention on an abortion referendum in her home state did nothing to sway the result, and there is a sense too that the way in which politicians, especially the Biden administration, fall over her for her endorsement borders on the absurd.

But her business skills – or her ‘power moves’ as she refers to her own acumen in the song ‘The Man’ – are both considerable, but also very far from being the main reason for her fame. It is a mark of her uniqueness to think that she came up with the line “I swear to be melodramatic and true to my lover”, but also the brilliant savviness of the Taylor’s Versions project, whereby she wrested back control of her back catalogue taking advantage of the fact that she continued to own the copyright of her songs.

When it comes to the management of her career, one suspects the influence – perhaps both genetic and direct – of her financially savvy father: Swift used to tell her contemporaries at school that she would be a stockbroker when she grew up.

But there is no doubt that Swift’s principle achievement is to have created by the power of her music and her example, a change of direction away from selfishness towards kindness. Dylan was always acerbic; the Gallagher brothers were demonstrably offensive and the world is full of rock stars who don’t donate to food banks – and likely never consider it something which they might do.

Taylor Swift does and it is wonderful that she does. It seems to me as though she is an aspect of something which appears to be happening the world over: a realisation that the values of self-interest which arguably date as far back as the Renaissance are insufficient to live by. We vaguely know this – but sometimes it helps if someone sings about it too.

See our other cover stories: