Christopher Jackson

No matter how hard the King’s lighting team tries, it is difficult to create an intimate space. He speaks in front of a picture of his late mother – he is addressing the nation as a son in grief as much as a new monarch – but behind him the room recedes into marble pilasters, state-of-the-art rugs: the scale proper to a King.

Charles says: “Queen Elizabeth’s was a life well-lived; a promise with destiny kept and she is mourned most deeply in her passing. That promise of lifelong service I renew to you all today.”

Perhaps the most important word in that passage is ‘all’. King Charles III is, whether people like it or not, the King of not just England, but of Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland too. Perhaps there has long been a degree of tension in this fact: it is a leitmotif of any biography of the Royal Family that the subject must preside over a United Kingdom peppered with nationalist sympathies.

Charles has known this from first-hand experience since the stressful day of his investiture at Carnarvon which took place amid rumours of an imminent bomb, and on which occasion a member of the public threw an egg at the Queen’s carriage.

His position, while it remains this nation’s main marker of stability, also has its uncertainties. These might partly be to do with being pelted with eggs – the same thing recently happened to Charles himself – but are just as likely to be felt as unease about the monarchy’s own relevance in the modern era. In an age of acronyms – of AI, AGI, NFTs, and LMAO – what relevance can the elaborate language of a court circular have?

It doesn’t end there. In a time of iPhones, of TikTok and Snapchat, what do we feel, if anything, about the deep past from Charles acquires his position and authority? And is palatial opulence permissible in an age of strikes amid a ‘cost of living’ crisis? In a time of drones and clones, can we experience emotion at all at the sceptre and the anointed oil? In short, what does history mean in the present?

Personally, I think the answer is that it means a great deal. But it is a question every monarch must answer.

Charles continues: “In the course of the last 70 years we have seen our society become one of many cultures and many faiths. The institutions of the state have changed in turn.”

When the speech is shown again on the ITVX documentary The Real Crown, we see him from a different angle: one of those images which shows the cameras and the soundman’s booms, and what it’s like for the King to be filmed. Then we see just how big the room is, tapering off, like Las Meninas, towards other rooms, and corridors and flights of stairs.

The King, with his bent, careful septuagenarian tread moves across a room larger than many people’s houses, to become framed in a doorway far larger than one might have imagined: he waves at the assembled camera crew, but also at us: his nation.

Streamlining

Since Queen Elizabeth II reigned for such a long time, we have almost forgotten that a change of monarch has a bearing on how we feel as a country. Since we are all citizens as much as we are individuals, the accession of Charles III therefore impacts in surprising ways on one’s own identity. We are used – all too used – to experiencing this with respect to the current prime minister is. This information, though it is clearly an external matter, also turns out to be vital to our own lives: we feel differently when Rishi Sunak is prime minister to how we felt when Liz Truss ran the country.

The question then of what kind of man the King is, turns out to be strangely shaping in terms of our own lives. This fact alone is the best barometer one has of the power of monarchy to alter and affect us, and to matter. For this article we spoke to those who have worked with and for him, those who have known him since childhood, and even those who know him only from his handwriting, to seek to understand our new monarch.

What emerges is a man of unusual sensitivity and empathy; someone kind, but also capable of obstinacy. Despite a certain fastidiousness – some will remember his frustration over being given the wrong pen at a signing ceremony early in his time as King – this is not a monarch without imagination or creativity. Perhaps above all, he is – in a rather refreshing way – an unusual man.

He is also a man of unusual experience. With tens of thousands of state visits to his name, the King knows the country better than anyone. Of course, there are severe constraints placed on the nature of his experience. His visits must all be conducted through the prism of the fame conferred by his role: his is a life of people on their best behaviour, a world to some extent cordoned off from unguarded human experience.

This state of affairs is something Charles has long since railed against. According to Jonathan Dimbleby’s masterly The Prince of Wales: A Biography, as early as November 1978 the future King would write pleadingly to his then assistant private secretary Oliver Everett: “I want to consider ways in which I can escape from the ceaseless round of official engagements and meet people in less artificial circumstances.’

Even so, the sheer range of his experience of the world even at a ceremonial level is one possible reason for the empathy he’s shown as King so far. In an age where most of the public sector is on regular strike, and with the rest of us experiencing rising inflation, Charles has already given an intelligent lead. Opulence is out, and frugality – insofar as is possible in such a gilded situation – very definitely in. This means that we are experiencing a decidedly ‘scaled back’ Coronation year. Meanwhile, for those who work for the Royal Household, the era of the grace-and-favour home is over.

For Michael Cole, the royal writer and broadcaster, and former BBC TV Court Correspondent, the King has begun his reign wisely: “The King is right. Slimming down the Royal Family is in tune with the tough times faced by millions in Britain and his 14 overseas realms,” he tells us.

So what is the reason for this approach? “The King is responding to the realities of the world. It is nonsense with royal knobs on to suggest that the King’s eminently sensible proposal to focus on the direct line of succession, Prince William and nine-year-old Prince George, will bring the monarchy to “the brink of collapse”, as a recent study by the think-tank Civitas ludicrously suggests.”

This Civitas report, authored by Frank Young, created a minor storm, claiming that without Princes Harry and Andrew working for “The Firm” the Royal Family “will disappear from public view”.

In disagreeing with this, Cole explains how the new slimmed down Royal Family will look: “Never again will we witness more than 20 members of the Royal Family on the balcony at Buckingham Palace. The King knows instinctively that this sends the wrong message. And he’s right.”

For Cole, Charles has taken inspiration from the past: “A keen student of his family’s history, he’s following the lead of his grandfather, King George VI, who led this country through war and economic austerity. He said the Royal Family was best when it was “Just us four” – himself, Queen Elizabeth and their daughters Elizabeth and Margaret.”

It is a reminder that Charles has always loved History and English as subjects. For Cole, this puts His Majesty in good stead: “The King has read the national mood and correctly decided “less is more”, which the late Queen certainly believed. Civitas 0, King Charles 5 – himself, William, George, Charlotte and Louis, in that order.”

Keen Interests

After Charles conducts that characteristic hunched pivot to wave goodbye to the cameras, and walks on to his next engagement, I am reminded that it is sometimes rumoured that both the King and the late Queen have been said to dislike Buckingham Palace, with each preferring their country residences. Balmoral has been particularly loved by both monarchs.

In the Queen’s case, this preference might be put down to a sheer love of the great outdoors. In respect of Charles, a more complex and intellectual figure, I am reminded of Sir Kenneth Clark’s observation that nobody in the history of civilisation has had an interesting thought in a Palace; that requires, Clark said, a room of one’s own, of the sort Virginia Woolf pined for. That’s precisely, of course, what Charles hasn’t had: privacy, and the ability to shape a distinctive personal destiny without the encumbrances of duty.

But the people we spoke to for this article attest that he has worked through these difficulties, with many emphasising the help of the Queen Consort. In fact, Charles has done something rather more interesting than complain about his lot in life. He has continued his intellectual passions while carrying out his duty. If one considers the success of the Prince’s Trust, it could be argued that nobody – with the possible exception of his mother – has done more good in this country over the past half a century.

One has always been conscious of Charles’ intellectual curiosity. It is the trait which most defines him, and which propels his astonishing work ethic which now percolates the Royal Household and which all courtiers must now get used to. It is this restlessness which was at his elbow when he wrote the famous Black Spider Memos to the Blair government in the 1990s on everything from the armed forces, to arcane aspects of agriculture and education.

He is always well-informed – sometimes, in fact, to a nearly ludicrous extent. It was said of Bach that his genius is tragic in that his cantatas were far better than they needed to be for a regional kappelmeister to justify his position. Charles is a little like this: his energy can’t quite be contained by the position he has; it keeps spilling out.

One representative story is of Lee Elliot Major OBE, the country’s first social mobility professor, who was honoured by the King at Buckingham Palace. “When I received my OBE, it was Prince Charles who was presenting the medals,” he tells me. “I was in a long line of recipients and I was doing a lot of reflection about what it meant in terms of my own life.”

It is a reminder that whenever Charles meets anyone for the first time, it is always in this context: it is for him to help his subjects navigate the sheer oddity of the moment. “He asked me about the Sutton Trust, and he knew about my social mobility work,” continues Major. “In the end, they had to prise me away because we were chatting so much. Now you could say he was simply well-briefed by the officials around him, but I think it indicated a personal conviction.”

Of course, it’s likely the case that a double whammy is in play: the King is both well-briefed and speaks from personal conviction.

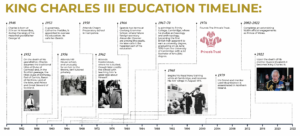

All of this makes one wonder a little about his education. Was there some germ in the deep past which sparked the King’s curiosity, or was it innate, even a sort of Royal anomaly? Interestingly, when Kings and Queens have considered their offspring’s education, they have generally plumped for precisely what Elliot Major advocates for the rest of us: one-to-one tutoring. “When done well it is the ultimate in education,” he continues. “I would argue that the rates of learning you get from one-to-one tutoring are the best you ever get. You’re never going to match that in a classroom: provided you get the chemistry right.”

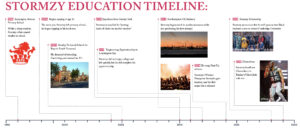

In fact, the future King was educated for a brief while by a governess: Catherine Peebles. But when it came to prep school age, he became the first monarch not to be educated by private tutors, instead attending a variety of schools. It might be that this exposure to his subjects has created in him a more empathetic persona than we’re used to as monarch.

If so, he suffered a little for his people. It is widely known that Gordonstoun was an unhappy experience for him. At Gordonstoun, it seems that the injunction for Charles not to be treated any differently from other pupils led to an appalling bullying culture which is horrible to read about today, with the then Prince deliberately picked on during rugby matches and so forth. As the Coronation ceremony approaches perhaps there are a few privileged people in their late seventies feeling shame for the way they treated the King some six decades ago.

As the novelist William Boyd, who was educated there alongside the King, has said: “Being educated over a 10 year period at a single-sex boarding school in the north of Scotland has a massive effect on your young personality and nature. What is then required is an equally massive process of re-education.”

This, of course, is precisely what Charles would do. But what receives less press than the King’s unhappy time at Gordonstoun, is his education at Hill House School, presided over by the redoubtable Colonel Townend. This turns out to be rather more interesting. The restauranteur Philipp Mosimann, who also attended Hill House, recalls: “It was a very simple ethos. The Colonel believed in life skills.

He believed you should learn to swim before you learn to read and write, because that would actually save your life. He was also a huge advocate of team-building. His father had been a priest and he had fought in World War Two; he used to show us videos of A Bridge Too Far. He went on to win two gold medals in the Empire Games. He was a real hero.”

One can immediately glimpse the parallels between this ethos and the values of the Prince’s Trust, Charles’ great contribution, which he would found a quarter of a century later.

Mosimann continues: “I remember these massive sermons the Colonel would give which the parents would attend; they’d just sit there enthralled. If you were well-behaved, you’d be invited to go up the mountains at weekends. It was fantastic; it was a child’s dream of education. It was all about getting out there, becoming friends and creating camaraderie. Townend believed strongly in becoming an all-rounder. Music was very important; it was mandatory to play one – if not two – musical instruments.”

And can Mosimann recall what effect all this had on Charles? “There is a wonderful picture of Charles when he arrived in Knightsbridge with the Colonel. It really was marvellous; and it imbued you with the idea that you had one education from your parents but they won’t give you everything. For the right reasons, the King became quite humbly confident.”

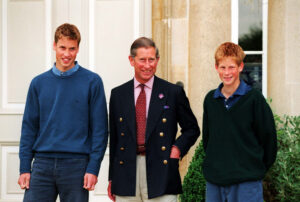

Looking at this picture, I feel similar emotions to what I feel whenever I see images of the young Prince William or Prince Harry, and indeed when I meet any young child: one has a sense of rooting for the young, and half-wishing the adult world won’t ever encroach upon them. One feels the same when one sees images of Charles as a young man: slender, slightly reminiscent of Gussie Finknottle in the PG Wodehouse Jeeves and Wooster series. Whatever one thinks of his privilege, one cannot ignore his vulnerability.

Philipp Mosimann says: “I think it’s very difficult to be King. When it comes to friendship, you have to be cautious with regards to your position, and they don’t have any choice about that. It’s a huge amount of responsibility for life, and you owe that responsibility to millions around the world.”

Most of us, even prime ministers, seek development, the forward steps of a career. Charles hasn’t had that. As Mosimann says: “If you take that decision seriously and do good – which Their Royal Highnesses really are doing – there’s not much rest. It’s a full-time job. You could say: ‘I’m okay financially and I’m off’. But they don’t – they uphold their duty. I think in terms of friendship, that may suffer in terms of time, so they need to have a close circle of friends from a very young age.”

Baron Levene of Portsoken, the former Chairman of Lloyd’s of London, who has interacted regularly with the King throughout a long and successful career, adds: “You can’t compare members of the Royal Family to the rest of us, even to prime ministers. A member of the Royal Family is always going to be in their position and will try hard to keep out of anything controversial. Members of the Royal Family are all trained and brought up in the same way but are all entirely different characters.”

In our lives, we wonder how to gain a position, and then how to develop that position towards greater fulfilment – the succession of steps which we call a career. A Prince or King must decide what to do with the position they have. Mosimann explains: “If you know you have a guaranteed position, how do you go about resonating your presence?” This question has been percolating Charles’ mind since youth, and no doubt still does even now. It is the conundrum of his life.

The High Seas

But he has had a career of sorts, somewhat apart from his Royal role. Over time, after attending the University of Cambridge to read Archaeology and Anthropology, the future King chose to carve out a role in the Royal Navy. These experiences, together with what he had learned at Hill House, would also impact on the King’s thinking and shape his contribution.

If Prince Charles had a mentor then one would have to name Lord Mountbatten, the maternal uncle to Charles’ father, Prince Philip. Dimbleby calls him “the great single influence on his life”. It was Mountbatten who, through his wife Edwina, came into the country house Broadlands, where Charles spent so much of his time in the 1970s.

Liz Brewer, the etiquette expert and contributing editor of Finito World, remembers this period: “The King founded the Prince’s Drawing School, which is now the Royal Drawing School. I would arrange for the school to go fishing on the River Test.” Founding things is a continual thread in Charles’ life. And Mountbatten? Brewer recalls: “Mountbatten was very dapper. He’d be very much at home in today’s world.”

Mountbatten was certainly an interventionist presence in the Prince of Wales’ life; most people know about his failed efforts to ensure that Charles would marry his granddaughter Amanda Knatchbull, now Lady Amanda Ellingworth.

Less well known is Mountbatten’s role in persuading Charles to join the Navy. For instance, Mountbatten wrote to the then Prince in no uncertain terms while he was still at Gordonstoun: “I would like to repeat…I am quite certain that you must have a “mother service” that you really belong to and where you can have a reasonable career. Your father, Grandfather and your Great Grandfathers had a distinguished career in the Royal Navy. If you follow in their footsteps this would be very popular…”

As ever with Charles, that’s a lot of footsteps to follow in. If anyone has ever felt nervous about starting some new chapter in their lives, then perhaps there will be a degree of comfort to know that their current King has known that trepidation too. Here he is on the eve of attending the Naval College: “I am beginning to pale at the thought of what Dartmouth is going to do to me. Whatever it is, it’s going to be far worse than the most excruciating tortures they could ever dream at Cranwell! [where Charles had spent five happy months with the Royal Air Force beforehand].”

Dartmouth in those days was a strict environment, and another challenge for someone of so sensitive a nature as the future King. After his first weeks, Charles reported back glumly to Mountbatten: “I have hardly had a moment to breathe since I arrived. We get up at six a.m. most days and have to suffer the early morning indignities of being bawled at by a Whales Island GI [i.e. gunnery instructor] with a voice like a horse. It’s either that or torture by Morse Code.”

This sounds, and probably was, fairly awful. But elsewhere in his correspondence, Charles strikes a more positive note. “Everywhere I look my eye catches some familiar face peering down at me from a portrait on the wall. Papa wrote and said I could console myself with the thought that I was serving ‘Mum and Country’! I hope I can and it fills me with pride to think I might be able to be of some service.”

Reading between the lines, more consolation was needed here than was provided for by his parents. Even so, it had its good effects. Today everybody reports on the King’s work ethic, and it is tempting to think that the lineaments of this may have been established at Dartmouth.

Either way, not everything went right for the King. When he eventually took his place on board Norfolk (‘this mighty vessel’ as he called it) he was self-deprecating about his abilities: “Chaos reigned in the charthouse. No sooner had I completed my artistic handiwork than the navigator appeared and proceeded to rub everything out…In the end the ship sailed in the direction of my revised lines and by some curious accident Plymouth hove into sight at approximately the right time in the morning. My relief was ill-concealed..!”

But to struggle in a strict environment is surely a good education for a future King. He didn’t have things his own way, and this experience has enabled him to imagine his way into the lives of others less fortunate than himself.

A former serviceman tells me: “I know he was very fond of his time in the Navy. He is a proud naval officer.”

The same interviewee tells me that the experience may have had its impact on the principles underpinning the Prince’s Trust: “I think, of all the services, the Navy – especially compared to the Army – is more of that collaborative working approach.” And why is that? “Everything has such a specialist role from your radar operator, to your torpedo-handler. It’s not just raw leadership – shouting at people, leading men over the wall – it’s training people to a high degree and empowering them to do the jobs they’ve been trained to do, and collaboratively being a team. It’s a different leadership style.”

Throughout his time in the Royal Navy, Charles grew in confidence. His career is a reminder of the salutary effect of having to test one’s potential against confines – and even to toil for some period at what one isn’t necessarily suited to. But he was beginning to feel that he could, in his own words, ‘be more useful elsewhere’.

Hard Slog

After leaving the Royal Navy, Charles began the relentless and essentially ceremonial life which he has kept up ever since. In 2022, at what for everyone else is retirement age, this has been ramped up again.

What sets him apart is that he has done all this, and yet given the impression that it isn’t quite enough for him. He can seem a sort of activist Prince Hamlet, somewhat at odds with what he has been born into.

The more you examine is life, the more you realise that what he craves is depth of experience in addition to the breadth of ceremonial experience he cannot avoid.

In the letter to Everett I quoted earlier, the then Prince goes on to say: “I want to look at the possibility of spending, say, 1. Three days in one factory to find out what happens; 2. Three days, perhaps, in a trawler (instead of one rapid visit); 3. Three or four days on a farm. I would also like to consider 4. More visits to immigrant areas in order to help these people to feel that they are not ignored or neglected and that we are concerned about them as individuals.”

This is a wholly admirable letter which I find it hard to imagine any other heir to the throne writing. Perhaps the most characteristic part of it is the request for that extra day on the farm, but all of it is shot through with a restless energy wholly his.

So what is life like for him? Baron Levene of Portsoken got to know the King when carrying out his stint as Lord Mayor of London. “I know him reasonably well,” he tells me. “He’s waited a hell of a time to do this job, even after such a short time. He’s very well-informed on many, many subjects.”

Levene is sympathetic to the enormously demanding nature of a life dominated by ceremony. “When I was Lord Mayor – not nearly as bad as being the King, of course – I shook hands with about 70,000 people over the course of the year. You have so many formal dinners and banquets and ceremonies. It’s very demanding – not intellectually, just physically. I used to get up at seven and go to bed at midnight every day.”

So is it possible to enjoy a life dominated by such a punishing schedule where you must always be on your best behaviour?

“I enjoyed it but it’s very tiring,” Levene replies. “When people at the end of it all asked me what I thought of it, I said a third of it was terrific, another third was okay – and the final third was ghastly.”

This then is Charles’ reality – except in the crucial respect that he doesn’t get to finish after a year. Levene continues: “When I was Lord Mayor I went to a wedding in London of a member of the Royal Family, who I happened to know well. I was sat next to the Queen of a well-known country. She said: ‘Look, it’s alright for you, you can stop after a year’. And if you look at the Court Circular each day, they go to the most obscure places: it’s undeniably a hard slog,”

I decide to do this and land at random on the Court Circular for 5th April 2023. It reads:

The King and The Queen Consort this afternoon visited Talbot Yard Food Court, Yorkersgate, Malton, and were received by His Majesty’s Lord-Lieutenant of North Yorkshire (Mrs. Johanna Ropner) and the owners of the Fitzwilliam (Malton) Estate (Sir Philip Naylor-Leyland, Bt. and Mr. Thomas Naylor-Leyland).

Their Majesties, escorted by Mr. Naylor-Leyland, toured the Food Court and met local business founders and owners.

I note the plural ‘local business founders and owners’ and note how such an occasion might proliferate. I try to imagine how each of those business people is experiencing the highlight of their year, and perhaps of their lives, and how the King must be mindful of this, and cannot afford to put a foot wrong. But the day isn’t over yet:

The King later met representatives of local charitable organisations at York House, 45 Yorkersgate, Malton, and was received by the Co-Founder and Director of Circular Malton and Norton Community Interest Company (Mrs. Susan Jefferson).

It is an unending round whose ground note can hardly be anything besides banality.

The longest serving Foreign Secretary of Australia and former High Commissioner of Australia Alexander Downer has also seen all this up close. “When I was High Commissioner of London, with Australia being a realm country, I would deal with Buckingham Palace a lot, but also with the Prince of Wales, as he was then,” he tells me.

Had Downer met him before? “I’ve known Charles a long time, as he went to Geelong Grammar where I also went. I first met him here in London when I was 13 and he was a couple of years older, 15. I wouldn’t call it a friendship, but a friendly acquaintance. With someone as famous as the King of England, if you know him at all you might say you were great friends, but that wouldn’t be right!”

Downer describes for me the level of detail which goes into each event. “In general, I would meet him more at events. But on one occasion, the Prince of Wales and Camilla – now the Queen Consort – were planning a visit to Australia, so I went to talk to him at Clarence House about what he might do while in Australia, and then we had follow-up meetings.”

Was he good at assimilating information? “As the Prince of Wales, he had advisors and people he would learn from, and he read a lot as well –

a thoughtful kind of person. If you’re the King, you have to be interested in everything as best you can be. I’m not sure how interested he is in the weekend’s football. Would he watch a Formula One Grand Prix? Would he watch Chelsea drawing with Everton? My guess is he’s interested in horses, like his mother was.”

This predominantly ceremonial life sometimes yields amusing anecdotes. Royal Warrant Holder Wendy Keith, the eponymous founder of shooting stocking design firm, Wendy Keith Designs says: “I attended a Reception at St James’s Palace with my husband who was a Senior QC at that time. In conversation, His Royal Highness asked my husband what he was doing there. My husband replied: “I am merely a companion to my talented wife”, to which the reply came :“I know the feeling!”.

When smiling at such a remark, one must take a moment to remind oneself of the punishing routine of the man who made it.

Scenes from the Chase

In addition, all this activity must take place in the glare of the world’s most brutal tabloid media.

In light of what happened to his first wife Diana, Princess of Wales, this is naturally a painful topic. But it needs to be admitted that there are many excellent journalists in the UK whose aim is to report legitimately on an important part of our national life.

One such is Michael Cole, who recalls for me a visit made by Charles and Diana to the US in the mid-1980s, when he was the BBC royal correspondent. “In many ways, Princess Diana was a wonderful person and quite easy to report upon, and not just because she was the cameraman’s dream, incapable of “taking a bad picture” — i.e. she always looked wonderful,” he recalls.

“The Royal Family made big mistakes in the way they treated her and especially in not giving her a greater speaking role and much earlier. On her first visit to the United States, in 1985, there was a major news conference at the National Gallery in Washington. What is the point of a news conference? To ask questions that elicit answers and to record those answers for possible broadcast or other publication.”

This seems a reasonable enough assessment, but things didn’t quite transpire as Cole was expecting. “Just before the conference was due to start, Michael Shea (then press secretary) announced that the Princess would not be speaking and her husband, Prince Charles, would not be taking any questions at all about the Ball at the White House the previous evening when Diana had danced with John Travolta, among other lucky men.”

PORTSMOUTH 1981

Something of a fandango ensued. “These were absurd restrictions and I told Michael that I would be ignoring them, not least because the White House official photographs of the Princess and the star of Saturday Night Fever were on the front page of every American newspaper that morning and had been shown and discussed on the major morning news shows.”

When questions were invited, I stood up and said: “Would Prince Charles be kind enough to let us know how the Princess is finding her first visit to the United States and in particular how she enjoyed dancing last night with John Travolta?”

Cole continues: “Prince Charles was livid. His face contorted with anger. He began by saying that he was not “my wife’s glove puppet” but then just about managed to offer a reasonable answer. The exchange is visible online.”

Cole took the following lesson: “It just proved how unwise it is for so-called PR professionals to try to shackle a free media, especially when there is not the slightest hint of a good reason for doing so; I wasn’t asking about State secrets or probing intrusive personal matters; I was asking for basic information about a story that was already well known and the point of conversations worldwide.”

Of course, he was asking – albeit tangentially – about the state of what we now know was an unhappy marriage, and so in retrospect one can imagine that Charles’ frustration on this occasion opened up onto the broader frustration of hi not being with Camilla.

The story has a sequel: “When they did start to allow the Princess to speak – or rather when she asserted her wise and instinctive wish to speak for herself – she did so very effectively and always made an overwhelmingly positive impression on her audience. It was just a shame that it wasn’t allowed much, much earlier.”

Cole says: “I have often reflected on this truth: if you stop running, they will stop chasing.”

Itsy Bitsy Spider

But chase they do – and chase we do. It strikes me that the desire to hunt for the King’s personality is especially absurd when one considers not just the expansive quotations in Dimbleby’s book but also the so-called Black Spider Memos released in the mid-1990s after a Freedom of Information request. Partly because the King expected these not to be made public, they are the best window we have into how his mind works.

When the Black Spider memos were released there was an attempt to treat them as scandalous. But really they’re a reminder that policy, when you get right down to the detail, is never scandalous. There is in reality something impenetrable about the memos, which renders them a non-story. The Prince was accused at the time of lobbying, but really one might as well accuse him of being extremely knowledgeable about certain topics: especially, agriculture, education, the condition of troops in Iraq, and, his guiding passion, the environment.

“You have certainly managed to bring together a powerful alliance of N.G.O.s and countries,” the future King writes in one letter to the then Minister for the Environment Elliot Morley. “I particularly hope that the illegal fishing of the Patagonian Toothfish will be high on your list of priorities because until that trade is stopped, there is little hope for the poor old albatross, for which I shall continue to campaign…” Morley’s reply isn’t readily available in The Guardian archive.

To the then prime minister Tony Blair, Charles writes: “The main issue that we talked about was agriculture. I mentioned to you the anxieties which are developing, particularly amongst beef farmers and to a lesser degree sheep farmers, of the consequences of the Mid Term Review. There is no doubt that decoupling support from production provides many opportunities, but it is also creating some real fears amongst the livestock sector.” The letter which ensues contains eight points full of closely argued detail; it resembles a legal brief. One is left in no doubt that this is a man who knows what he’s talking about, though the correspondence is very far from being a page-turner.

“As you know, I always value and look forward to your views – but perhaps particularly on agricultural topics,” replies Blair, possibly through clenched teeth.

My guess is that it’s this which makes Charles standoffish with the media: there is no scandal about him, but the questions he has to field always seem to suppose that there is, might be, or even should be, scandal. It is always annoying if you want to enact a change to agricultural policy to be asked about your divorce. Charles cares about other things and other people; but the media keeps wanting to turn things back to him.

There is a complexity about our current monarch. The Queen, with her stoicism and an intellect which didn’t range quite so widely as does Charles’, was perhaps more comfortable with the symbolic nature of the role she was called upon to enact. Charles isn’t like that, and so perhaps he will make us all look inwards and wonder what more we might be capable of. One can imagine a nation more analytical, perhaps even, in some positive sense, more curious with him as King.

A Question of Trust

Nevertheless, the fact that he is human is another non-story and therefore another inconvenient truth for journalists.

Philipp Mosimann tells me an excellent story which encapsulates this perfectly. “Mosimann’s has been very involved in the Prince’s Trust,” he explains. “We had a gentleman who became an apprentice on one of the cooking programmes, and we hosted him at an event with the King in attendance. The apprentice had written a long speech to thank the future King for what he had done for his life chances. But when he came to deliver his speech, the apprentice broke down and cried and the whole room was filled with tears.”

The next person to speak was Charles. “It caught him off guard and he welled up, laughing and crying at the same time, and it was a lovely down-to-earth moment. Literally, his eyes had filled with tears. I will never forget that. You realise why we’re all here.”

It was a moment of tremendous levelling. “We were all there in the same room and everybody was at the same level and having the same emotion, about the chance we all have to change people’s lives.”

It is a lovely story, and very revealing in its way, but I can’t imagine it being front page of the Mail. The unglamorous humanity of the King and his endeavours is also echoed in Lord Cruddas’ experience. “If you work with the Prince’s Trust, you meet people who have been in difficult situations – maybe members of gangs, or drug addicts who have pulled themselves together,” he tells me. “You meet people on the front line of society, and it’s very sobering and it keeps your thinking on track.”

Cruddas recalls one moving occasion: “I was at this exhibition and walking around with King Charles. Everyone was treating me as an important person as I was with him. At the end of it, a young woman called Gina came up to me and said: “Thank you for everything you do.” I thanked her. And she said: ‘You don’t know me. If it wasn’t for people like you, I’d still be in prison. Because of your work with the King, I’m now a florist and I can look after my three children every day’. It’s a very rewarding charity.”

Of course, no assessment of King Charles would be complete without an understanding of The Prince’s Trust, which Charles founded in 1976 – amid, according to Dimbleby, much scepticism from his parents.

It sometimes seems as though you have to try hard to find a senior business figure who hasn’t been involved with The Prince’s Trust.

In our tribute in this issue to Lord Young of Graffham, Sir Lloyd Dorfman explains the charity’s evolution. “Whilst the charity had been founded by the then Prince of Wales in 1976, David Young had helped accelerate its growth. He was supportive of the charity enabling young people from underprivileged backgrounds find jobs and also start businesses. As Secretary of State for Employment and then for Trade and Industry in the 1980s, he famously devised a matched fund-raising scheme to support the Trust’s enterprise work. The government ended up committing millions of pounds, much more than had been imagined, to the surprise even of his Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.”

One of Britain’s best-known entrepreneurs is John Griffin, who founded Addison Lee. He famously began with one car and forty years later sold the Company for £350 million. He effuses praise about The Prince’s Trust. “As a young man, I watched my own employer and thought that I could do better. It wasn’t that I was unemployable but there was a burning desire to prove to myself that I could achieve anything that I wanted. To be an Enterprise Fellow for the charity is one of the best ways to inspire the next generation. I like their motto, “Start Something.”

“Even in my own octogenarian age, I am always looking to begin my next business,” continues Griffin, who is also Finito’s Advisory Board Chairman. “There are so many entrepreneurs who owe him a debt of gratitude for providing that early start and helping them on their way. I also commend King Charles III’s late father for The Outward Bound Trust, which teaches young people the two most important words in life “I can”.’

What is Cruddas’ assessment of Charles’ contribution? “If you look at King Charles, every single year he raises £100 million a year for good causes. He uses his status and position to help ordinary people and you have to admire that. He works hard at it. He’s not just a symbolic head of the Prince’s Trust.”

Finally, Elliot Major has this assessment: “When it comes to social justice, it’s not just about plucking academically able disadvantaged pupils and getting them to Oxford, Exeter, Cambridge or Durham. That‘s important, but what we want is diversity in the upper echelons of academia and society.”

For Elliot Major, the Prince’s Trust has the right focus: “In many ways, the bigger problem we have is the huge number of people who leave school without basic skills and often come from families who themselves have had a bad experience of education. I think what’s really good about their work is that it’s not just about academic talent, it’s about recognising that young people have different talents: it’s focusing on the unsexy side of social mobility.”

So along with the unsexy Black Spider memos, we have this unsexy charity. But there will always need to be people doing things which others haven’t the patience to grapple with. Elliot Major concludes: “Having interacted with them, I think that’s a laudable aim. It’s very practical in many ways; they definitely are doing good work.”

A United Kingdom

Since the late Queen’s death, everybody who works in the royal household, has had to get used to the King’s relentless pace of work: his curiosity, essentially admirable, isn’t passive. The Queen had a well-documented style of working, which in hindsight is already considered more relaxed than the new King’s. Meanwhile, the handover of staff must take place; those who used to work for the Queen are in many cases still in position, meaning that in some cases there’s more than one person doing essentially the same job. It is like a very high end company merger.

And, in fact, a merger where the main premises are undergoing a huge refurbishment (Buckingham Palace is receiving a one room at a time makeover), all while planning the first Coronation in most people’s living memory.

There’s a lot of work to do. The King waves in the doorway, and then walks off into the future. It is one that he has already done much to help shape.

What kind of country is he waving back at? It is a country which, in spite of the last few years, feels more united than one might have expected. It’s true that the new Prince of Wales, due to Welsh nationalist feeling, needs to decide what kind of investiture ceremony to have, if any. But one doesn’t get an immediate sense that Wales is about to leave the Union.

In Ireland, the ructions which Brexit caused have not only passed but the deal which may do a lot to create a return to power-sharing in Northern Ireland even has a Royal name: the Windsor Accords.

Finally, if Scottish independence is imminent after the travails of the SNP in 2023 then I am an avocado.

It is also a nation which is aligned in many ways with the new King’s values. Environmentally-concerned, aware of the importance of social mobility, and as his letter to Everett shows, mindful of the nature of modern Britain, and penny-pinching during a time of financial hardship, he may yet prove to be the right man for this historical moment. King Charles probably wouldn’t have chosen to be King had any choice been granted; and perhaps the nation, at various points, might have reciprocated this unease. But I suspect that over time, many will come to realise that we’re lucky to have him.