The words ‘literary lunch’ have a certain allure which may not be entirely due to alliteration. As the pandemic continues to retire itself from view, Costeau has seen the invites begin to trickle back – not with the traditional thud on the doormat, but with the ping in the inbox.

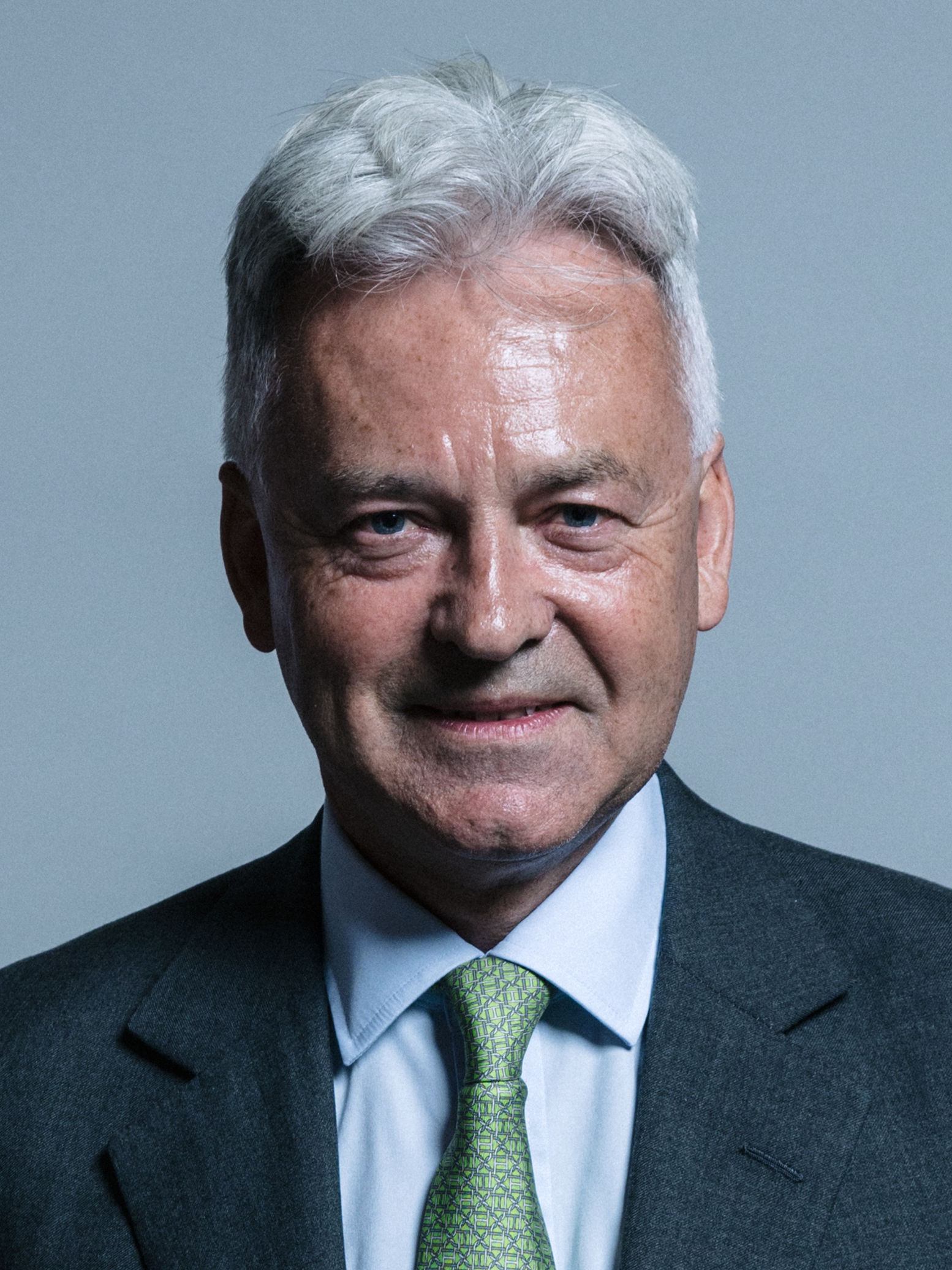

First up was Sir Alan Duncan, whose gossipy diaries have made a stir of late – particularly on account of his late night venting against colleagues when a minister.

Costeau turned up at the function at the University Arms, Cambridge to find something like the pre-Covid literary world restored. In fact it was somewhat of a hybrid event: books were on sale, and there was an air of excitement about ‘meeting the author’.

Costeau recalled all those lunches, pre-pandemic. One such occasion involved those nominated for the TS Eliot Prize, who had been dutifully lined up signing their books, trying not to register queue envy if a fellow author had attracted more fandom. Costeau saw that the line for the late Dannie Abse was a bit shorter than the others and duly deposited himself in front of him. Our conversation was underwhelmingly emblematic of these occasions: “How do you know my work?” Abse said, wearily. “I read some of your poems in the London magazine.” “Oh.” Abse shrugged his shoulders with palpable exhaustion. The poet died soon after, and Costeau has ever afterwards hoped that the event wasn’t the last straw.

Duncan went at the occasion with considerably more vim – his manner throughout positively thespian. That’s the thing about the literary lunch: it actually best suits a certain kind of Conservative politician. At a similar recent occasion Costeau saw Lord Ed Vaizey, though promoting no book, speak without notes for an hour. He gave the impression which Michael Gove also gives on such occasions, that there is no topic on earth for which he doesn’t have a 20,000 word speech readily to mind.

The paradox is that the collision of real writers with the public can sometimes be a stilted affair. Costeau recalls the late Christopher Hitchens speaking at a lunch in Oxford University. Having stayed overnight, the polemicist moaned about the quality of the beds: ‘They can’t stop you doing it, but they can certainly make it less fun.” Throughout his talk, he smoked the cigarettes and drank the whiskey which together would kill him, as if they were a lifeline from the tedium of the occasion.

On the other hand, mere readings – as opposed to lunches – plainly have their limitations. Attending such occasions can be dispiriting, and the experience is brilliantly satirised by Sam Riviere in his recent debut novel Dead Souls. In that book, everyone in the room offers up dutiful ‘words of praise’ – and this absence of risk kills the occasion without anyone even knowing it.

Duncan wasn’t exactly on edge at his lunch. He spoke to the assembled literati with a cheerful eloquence, even taking a moment to lambast a reviewer in The Guardian who had picked the book apart the weekend before. But he knew his audience would be favourable – it’s in the nature of the literary lunch.

In literary circles there’s a lot of talk about how readings don’t sell books, because they keep reader and writer at too much of a distance. In Costeau’s experience, literary lunches with their more intimate arrangements, do sell books as there’s a sense of greater connection, and therefore obligation between the relevant parties. Duncan himself wisely circulated the room offering to sign copies, thus engendering a minor guilt among those who hadn’t taken the plunge.

The literary lunch shall return, if only because there’s a perennial fascination about writers among people who don’t write. It is, after all, a very unusual and counterintuitive thing to set aside years of one’s life – really one’s whole life – to making marks on paper. The desire to meet and observe these unfortunate creatures is understandable.

The phrase itself retains a certain allure, conjuring associations of a Wildean and witty lunch where because other people sparkle, we sparkle as well. It’s essentially an aspirational thing – to do with bettering ourselves. That’s why the comeback, if it happens, shall be welcomed by Costeau: if ever there was a time to sparkle and really enjoy the possibilities of life, it’s now.