By George Achebe

Will we ever return to our offices? And what will they look like if we do? George Achebe talks to renowned designer Thomas Heatherwick

Journalists I speak to lately have begun to notice a new presence within their recordings of interviews and Zoom call presentations: birdsong. Lockdown coincided with marvellous weather; our offices became our gardens.

And the sky on our road in Islington reverberates with the sound of spanner on metal; our friends over in Muswell Hill have replanted their garden since they spend so much time looking at it; my conveyancing lawyer tells me he may, or may not, return to the office. If so, he says, it will be used primarily as a storage space.

There is, in other words, a unanimity about lockdown: you can be sure that your own experience can be extrapolated into the general. And yet if you ever leave your cosy home and venture to the centre of town, you’ll discover the flipside of all this neighbourliness and quiet domestic improvement.

Soho strikes me as especially melancholy. There’s the sandwich bar I used to frequent now boarded up; a new kind of silence, not so much contemplative as eerily touristless; and with around one in ten businesses open, you have a sense that this place has insufficient residential activity to last in its current form beyond the end of furlough.

Will these businesses return? It is dependent on what decision we make about our office arrangements. This varies from business to business of course. For a more in-depth analysis of the landscape see our exclusive employability survey which begins on page 79. But what are the implications for architects?

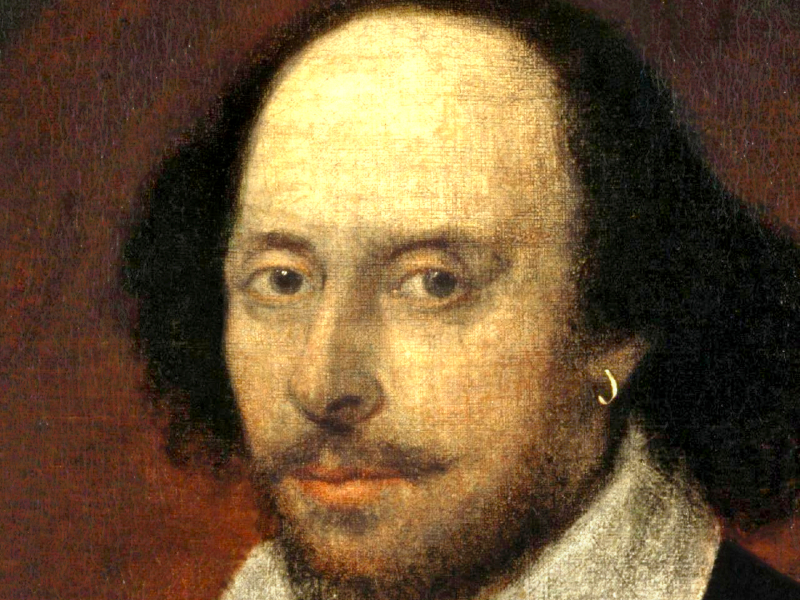

Thomas Heatherwick, the famous founder of the Heatherwick Studio, explains that he has seen some positives come out of the coronavirus period: ‘The most interesting thing has been reflecting on what this means and how it’s going to change our lives. I’m wrestling with the sense that [preCovid 19] there was more and more sharing – of cars, workspaces and living spaces. The world was becoming more efficient because people were learning to live together in different ways.’

In Heatherwick’s eyes, the pandemic represented a ‘retreat’ into the private space – a world of Victorian studies, and stockpiled toilet roll. But Heatherwick, who in person is infectiously optimistic and free-wheeling, is already solving the problem the world has set him: ‘The positive side is that people will be spending more time on their homes, and thinking on how their homes work for any situation.’ In the meantime, he says, businessowners have decisions to make about whether to redesign their office space.

We are all aware that this is a sort of drawn-out inflection point, where the human behaviour that will dictate what solution we end up with is latent, and yet to be revealed. Furthermore, it will likely differ from country to country; sector to sector; and CEO to CEO.

When I talk to Alan S – the CEO of a leading boutique creative agency, who also has the sound of birds in his garden – he speaks only on the condition that he remains anonymous. This is because he isn’t quite sure where his business will land and he doesn’t want to give any misleading or worrying information to his workforce.

‘As a small business we have always worked from a fixed office in central London and although we have let employees work from home when required we have never all worked remotely at the same time,’ he explains. ‘We did a trial run before lockdown was announced in order to iron out any issues that might possibly arise, so when lockdown happened we were as ready as possible.’ So how did it pan out? ‘The overriding response was that everyone found it productive, but missed the typical office interactions and camaraderie when seeing each other.’

This will no doubt be a familiar experience for many. What changes has that made to Alan’s view of his existing central London office space? ‘It suddenly became a burden and we were realising that the more we worked from home, the benefits this gave to everyone [would accrue].’ And what are these? ‘Everyone would save on travel expenses and commuting time could be spent with partners and families.’ The perennial bugbear or exorbitant business rates has also been front of mind for the business. ‘The rent, rates and insurance saved by surrendering a central London office will enable us to invest in people, equipment and technology to increase our efficiency and service our clients.’

So Alan S has to some extent made up his mind, and there are plenty of him.

But it is by no means a unanimous view. In fact you’ll find some who argue that an imminent vaccine, most likely arriving in 2021, and distributed towards the end of that year or in 2022, will see a return to a world reminiscent of pre-Covid 19 office-centric life.

Olly Olsen, the CEO of the Office Group, which has over 40 flexible workspaces across the UK, is one of these, although he admits it may be a way off. ‘I spoke to Network Rail, with whom I have a joint venture, and in a number of stations, footfall is down 88 percent. That’s catastrophic,’ he concedes.

In addition, Olsen, whose livelihood is bound up in office life, also makes some admissions about the benefits of working from home. For him, they’re linked to wellness. ‘In the afternoon, I get tired with too much coffee and a big lunch and so I’ll lie down on the sofa for half an hour which is almost socially unacceptable to do in the office.’ Olsen sees it as a positive future driver of business that we’re now finding ourselves more attuned to what he calls ‘wellness fluctuations’ in each other. Workers with children are another example. ‘It used to be that if someone said “Can I make that meeting 11 instead of 10?’, you’d say: “Deal with your kids another time.” Now when a member of staff says, “I’m not feeling myself ”, I say, “Have a rest, there’s no problem. Speak to you later, speak to you next week”.

All this is an indicator of how power has moved rapidly away from the employer towards the employee. For Olsen, it’s not that the office model needs to go; it’s that it needs to change and be adapted to reflect our new reality.

What ramifications will this have for the buildings around us? Thomas Heatherwick agrees with Olsen, but he sees it from an architect’s perspective. For him, there has simply been too much ‘lazy place-making’, and the pre-Covid office was a case of ‘Stockholm syndrome where someone falls in love with their captor. Your employer effectively had you in a headlock.’ The new office space will have to ‘engender real loyalty’ and become a ‘temple of the real values and ethical thrust of an organisation.’

For Heatherwick, the pre-Covid workspace ‘prioritised how [businesses] communicate to the outside world. So if you go to Canary Wharf ’ – an example perhaps of Heatherwick’s ‘lazy placemaking’ – ‘there’s a grand lobby; huge marble floors; pieces of art looking spectacular; a reception desk with great flowers, and lovely-looking people sitting looking great. But if you go inside the elevator you go up to just an ordinary place of work. The show was for the outside.’

All this has to change now that power has moved in the direction of the employee. ‘You need to have them coming in and thinking, “Yes. I need to be here.” So the workspace will become less about being a show for the outside world. It’s about finding your voice as an organisation. The employer has to up their game which the brilliant people were starting to do anyway.’

So how will this look? Heatherwick is a prescient artist who, it could be said, was already beginning to answer some of these questions in his previrus work. His magnificent shopping centre Coal Drop’s Yard in King’s Cross was all about creating a space which people who could internet shop in their bedrooms would still wish to visit.

‘Public togetherness is something which motivates me,’ he says with infectious enthusiasm. Heatherwick has always been alive to the fact that change must be built on the back of existing infrastructure: as always, the future will be built on the back of past structures. ‘We’ve got this legacy of Victorian and Georgian warehouses, which are very robust and changeable. Think how many people are living in older industrial buildings. That was the ethos which drove the Google buildings that we’ve worked on.’ Covid-19 might seem to open up onto the future, but it will also be anchored, Heatherwick argues, to what we have already.

The first project the studio worked on for Google was the company’s offices in California. ‘Next-door to the sites we were working on there was this airship hangar – a NASA airbase,’ he recalls. ‘These are amazing spaces which are super-flexible so you can do anything you want. So our proposal to Google suggested we make really flexible space since we’re not sure whether in a decade people sitting at desks will be what we need. We’ll be manufacturing instead.’

So in a sense the post-coronavirus requirement of flexibility might be met by the sorts of structures already around us: there shall be that element of continuity even as we change.

But this isn’t to say Heatherwick lacks a vision of just how extraordinary the shift in architecture shall be. Round the corner from his studio in King’s Cross, Heatherwick is working on Google’s new London base: ‘It’s the biggest use of timber in a central London building. All the façades are wood.’

What is the ethos of that building? ‘One thing we’ve spent time talking about on that is community,’ says the 50-year-old. ‘The idea that here is just a mercenary organisation doing their thing, and the employees come in eat all their food and drink their drinks, sit at their computers, and get well-paid…’

Heatherwick trails off, then refinds his thread. ‘Given what we’re saying about really getting a deeper engagement with an organisation and it’s team: How does that really contribute to the community around? On the ground floor, you don’t just want another shop that sells ties.’

So what would a new communityoriented architecture entail? ‘Close by King’s Cross there’s Somers Town, where there’s great deprivation and low life possibilities in terms of housing and education.’ For Heatherwick the lively pedestrianised ground floor is a way of energising the whole area.

So while our conversation began with fears of a new individualism, perhaps we might after all find a new communitarianism emerge? Heatherwick agrees: ‘If you’re going into work two days a week you may not need to be based in London.

Out of this may come some strong community-making away from conventional urban settings. Energy had seeped away from villages but now you could get super-villages. It’s okay to spend two hours on a train journey if you’re only doing that twice a week. I just hope we will use brownfield sites rather than consuming greenfield sites.’

But again this seems to spell trouble for the City and, though few may lament the fact, the property development sector. Olsen admits: ‘If you ask people where they most prefer working, it’s on their own – it’s at home where it’s quiet. Not an office which is openplan with people talking, and which is smelly and so on.’

So what’s the purpose of going to an office? Olsen is clear: ‘We’re built to connect. I can’t have guests and clients to my house and I can’t bring a team together to my home. If I do that business will fall – as it’s falling now from lack of human interactions.’

So what kind of spaces will we see? In answering this, Olsen sounds a lot like Heatherwick: ‘It’s difficult to forecast what will happen next but I think where you choose to work will be driven by who you are and what you believe. Our places of work will become more of an extension of our social lives.

The overwhelming impression is that we’re in a hiatus – a period of hedging, where people are living in tentative expectation of a vaccine. Olsen agrees (‘we just don’t know) but he has clarity on another point: ‘Before this happened, I would have said that all my buildings were clear, tidy, safe and healthy. Well, they’ll have to be clearer, tidier, safer, and healthier now.’

So it seems likely we’ll be hearing the birds in the garden for a while yet. And when we get back to them, perhaps we’ll hear them in our offices too.