Christopher Jackson reviews the latest Coldplay release

Every now and then I find myself considering the fine margins between major and minor success. I remember, for instance, a gig I attended at the turn of the millennium at the Nottingham Arena performed by the band Travis. In those days, like their rivals Coldplay, they could easily fill a stadium of 10,000 people. We may have turned up with a certain scepticism but ended up shouting out the lyrics to ‘Sing’, our cynical side assuaged by the fun of the evening.

Today, rotating on Apple Music, Travis’ songs have a power of nostalgia which the songs of Oasis lack. ‘Wonderwall’ has never really gone away. Travis, by contrast, have had a quiet few decades: this fact creates the gap in our experience which can make for a genuine revisiting not quite possible with the Gallagher brothers. And Travis’ songs stand up reasonably well. ‘Why Does it Always Rain on Me?’ ‘Sing’. ‘Driftwood’. ‘Flowers in the Window’. I hope they have a comeback.

But had you asked me in the year 2000 which band, Travis or Coldplay, would in 2025 break the record for the most consecutive gigs played at Wembley Stadium, I would have probably plumped for Travis. Coldplay at that time were mainly known for ‘Yellow’, which, lovely as it was, seemed to be a melancholic dead end. Travis’ songs seemed to have more complexity: they even sounded a bit like standards. One could imagine people covering them: there was more to explore.

I was wrong, of course. I’m not sure if Travis can still fill Nottingham Arena, but I know that it would be too small a venue for Coldplay. When A Rush of Blood to the Head came out in 2002, I was on the frontlines of the backlash, feeling that Coldplay represented not something new and lasting, but some form of decline from the greater cleverness of Blur and Pulp, those high spots of Britpop. Coldplay, I felt confident, represented the blandification of the British scene.

Change of Heart

I now see I was wrong in this reasoning – and wrong perhaps precisely because I would have been reasoning and not experiencing the emotion of the music.

All this came back to me recently when Coldplay returned to my life by a series of accidents. Our family’s enjoyment of ‘Something Like This’ in the car on holiday, led me to the Coldplay Essentials playlist on Apple, and via that to a discovery of all that Coldplay had been up to in the intervening decades since I had loftily decided that they would have no future. I note also that I never bothered between the years 2002 to 2024 to check in on whether my predictions had proven false or not.

At least I am not alone. As I read the other reviews of Moon Music, the album recently released to an almost Swiftian excitement, I realise I am not alone in having underestimated Chris Martin and all his works.

Almost any broadsheet review of a Coldplay album will begin with some disclaimer, making it reasonably clear that though the reviewers themselves have not written ‘The Scientist’ – or indeed any song of any description – that they are obviously above the task which has befallen to them: namely to review the latest Coldplay album.

Usually, there will be some sniping at the lyrics, and a general keening about Chris Martin’s perennial failure to be Gerard Manley Hopkins. From here, the reviewer, having restored themselves to intellectual respectability, will then go on to relate what I suspect might be their real feelings: namely, a few carefully caveated points of praise. It turns out that one or two of the songs are actually ‘not bad’ or in fact, in some cases, surprisingly good. It is then sometimes observed that this is true of most and perhaps all Coldplay albums. The eventual rating – usually three stars – seems to conceal a certain embarrassed enthusiasm.

If we take the typical reviewer’s estimation at face value that there are, say, two good songs on each album then it must be pointed out that this still amounts at this point to around 20 songs which even the naysayer would wish to preserve.

What is often forgotten is that this in itself is a high number. If we look at the amount of a celebrated pop act’s catalogue which we actually want to keep it usually turns out to be very small. We would probably be content with rescuing around 10 of Fleetwood Mac’s songs, and Fleetwood Mac is an excellent band. I’ve often thought the Rolling Stones really amounts to around 20 songs (they have released hundreds). It’s only when we get into the major acts, the Beatles and Paul Simon that we top 50 songs – and only in relation to Bob Dylan that we clear 100.

All this is to say that even if we take a negative estimate of Coldplay’s output then the band’s work is to be approached with respect and not derision.

The Ghosts of Modernism

Of course, one shouldn’t have to say this – and one wouldn’t have to say it at all if it weren’t for the peculiar way in which the 20th century turned out in terms of art. Really, it is an inheritance of modernism where people began to feel that things must be complicated, and even incomprehensible, to be good. This view would have surprised many artists and writers who university professors like to exalt, Shakespeare among them, who always took care to have a ghost or a murder – and ideally both – in his plays.

What appears to have happened by 2024 is that we have realised more or less unanimously that we quite dislike modernism, and wish to keep it at a safe arm’s length. We want to enjoy life, and that for most of us, means not reading The Wasteland or listening very much at all to Schoenberg.

This is not to say that Moon Music is full of ageless poetry: if written down, the lyrics can indeed be banal. But then this album never claims to want to be experienced in that way: it claims instead to be joyful – and joy-inducing – music. This has two ramifications at the level of the lyrics which are worth examining.

One is the propensity for simple and grand statements which at the level of language, a child could write. In the third single of this album ‘All My Love’, the lyric reads:

You got all my love

Whether it rains or pours, I’m all yours

You’ve got all my love

Whether it rains, it remains

You’ve got all my love

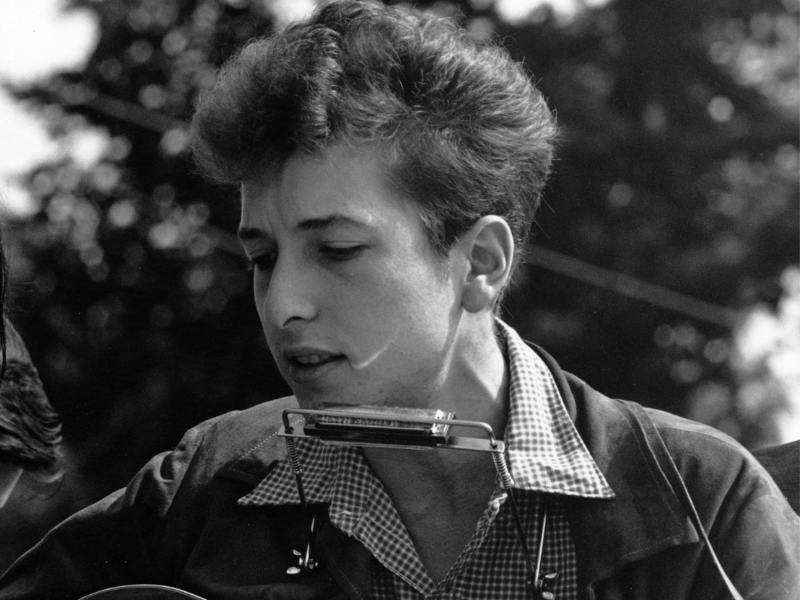

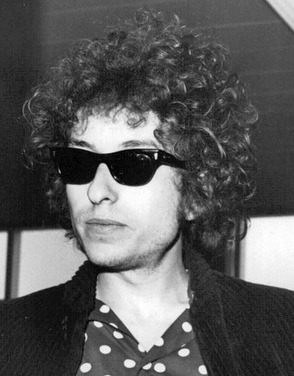

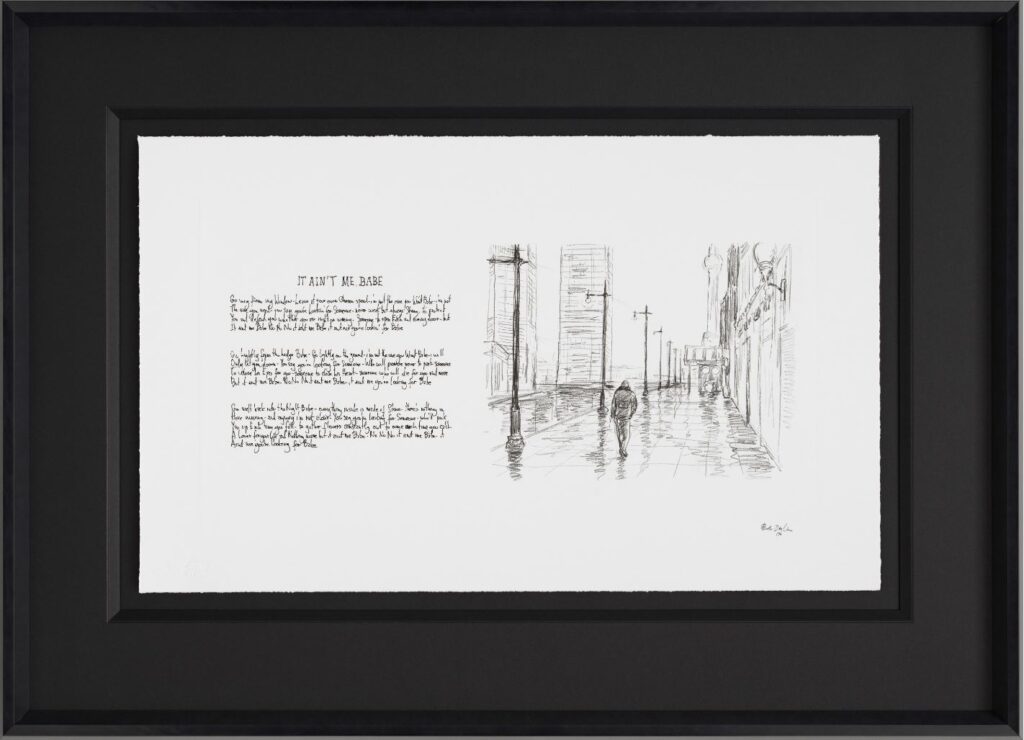

Now, we can certainly surmise that if T.S. Eliot were writing that as poetry that he might not be top of his form, and even having rather an off day. Bob Dylan, a different kind of songwriter to Martin, especially when writing in the 1960s, would if writing this song no doubt cram in additional internal rhymes around ‘pours’ and ‘yours’ with available words being ‘floors’ ‘pause’ and ‘cause’. He would glut the listener with ideas – and with every idea crammed in one can imagine it getting significantly less likely that the song would ever be sung in a stadium. The song would become more intellectual – would become another kind of song.

Martin doesn’t do this, and I think at this stage in his career we must give him the benefit of the doubt that he does it deliberately. To firm ourselves in this concession, let me pick almost at random an interview excerpt to show the intelligence of the man. This is Martin talking to The New Yorker in an article released to promote Moon Music:

“I’m so open it’s ridiculous,” he said. “But, if you’re not afraid of rejection, it’s the most liberating thing in the world.” Well, sure—but who’s not afraid of rejection? “Of course,” Martin said, laughing. “To tell someone you love them, or to release an album, or to write a book, or to make a cake, or to cook your wife a meal—it’s terrifying. But if I tell this person I love them and they don’t love me back, I still gave them the gift of knowing someone loves them.” Martin noticed a slightly stricken look on my face. “I’m giving this advice to myself, too,” he added. “Don’t think I’ve got it mastered.”

Now regardless of the ins and outs of the philosophical point here, I think most will agree this is obviously an intelligent man speaking who is probably in person wise, funny and kind. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that he should become less so when doing the thing he loves to do which is songwriting. In short, there is something forgivable about the lyrics when we consider the man.

So given the deliberate nature of his music, what is it which Martin is trying to do with a song like ‘All My Love’? With this kind of song, everything comes down to the sincerity with which it is sung. Sometimes, reviewers will accuse Martin of issuing song lyrics which are like Instagram self-help posts. This is intended to wound him, and perhaps it does.

However, even if this is admitted to, we have to say that there are two kinds of platitude: that which is meant sincerely and genuinely designed to help people, and that which isn’t really intended to help at all but which is really a kind of show, and therefore a sort of con.

On Sincerity

Having listened to Moon Music for the last few days, I don’t think it is at all the latter. I think Martin is someone who genuinely cares about his fellow human beings, and that his music is, by and large – with admitted peaks and troughs which are entirely human – a fair method of conveying what he feels about life. It was Emmanuel Swedenborg who wrote of insincere feeling that it were as if ‘a liquid were, on the surface, like water, but in its depths putrid from stagnation’. A certain kind of commercialised pop music is like this: it is, in its depths, false.

The impression one has of Coldplay is different. Probably it wouldn’t catch so many people, and cause such widespread delight, if it weren’t.

It was his friend Nick Cave who wrote of Chris Martin’s ‘songwriting brain’. Now that we have admitted that he has one, we can see what Martin is able to do in his songs. The interesting point about this is that the correct measure of true feeling does away with artistic doubt. Moon Music is full of what we might call surmounted cliché.

If I sing that I feel like I’m feeling falling in love, and I have – as one might in adolescence – no real sense of what that feeling means, I will sound rather silly. I will probably not convey that feeling with sufficient experience. Almost certainly, I shall sound immature and insecure, and if the girl is rejecting me, self-pitying.

But if I sing, as Martin does on the second track here ‘feelslikeimfallinginlove’, about falling in love with full consciousness of what that means – the fear as well as the joy, the vulnerability as well as the force of it – then the words, simple as they are, come hitched to meaning. In that scenario, the music has some sort of potential which exists completely independently of what has been written down on the page.

Similarly, if I pray for a better world as in the third track here ‘We Pray’ and with every fibre of my being, I really do wish for peace for my fellow human beings, and feel the genuinely awful corollary of war and all its disasters as I sing it, then I am able to bypass the literary concerns of even a music journalist for The Independent around a line like “Pray that I don’t give up/pray that I do my best’.

That journalist may write at length that I am using cliché, but will be missing the fact that in pop music, if I mean what I sing, and see the glory of peace and the horror of war in my mind’s eye as I sing it, their objections simply don’t carry. In this art form, to mean what one says is a sort of de facto defeat for the naysayer because no matter what The Independent might say, peace is really a very important thing, and praying for it is a very good thing to do.

At a certain point, Martin realised he could do this sort of thing again and again and that people hugely needed it. He is not Dylan or Cohen, and never intended to be. Musically, his chords progressions are extremely simple, and so he is also to be differentiated from the greatest player of stadiums Freddie Mercury. Mercury’s musical vocabulary was borrowed from jazz and classical. A song like ‘All My Love’ with its straightforward chord sequence from Am to D7 to G and Em shares nothing musically with Mercury’s ‘My Melancholy Blues’ with its complex diminished chords. In fact, Mercury’s songs would generally be a bit outside Martin’s ability as a piano-player.

Don’t Panic

But again, in a world of difference, there is no need to fret about any of this if the music can be made to convey good things honestly. It might all be summed up by the presence of an emoji of a rainbow as a track title on Moon Music. A rainbow is a cliché of course – but I know few people who don’t pause and point when they see one in nature. A rainbow then, like peace, or love is not just a cliché. It is also a vital thing which needs to be re-experienced.

There has been a lot made about Martin’s saying that there shall only be 12 Coldplay albums. With this being the 10th, we are therefore approaching the end of the band’s career. We should remember that it’s a career that has caused enormous amounts of pleasure to many people because of a certain fearlessness about finding ways to refresh us in relation to the obvious.

How has he done this? I think he has done it by trusting to the origins of songs. A few years ago, Martin explained that he was going through a hard time dealing with the inheritance of an evangelical upbringing. One’s sense is that like so many in the Western world, his struggle has been with the structures of religion – what we might call its exoteric aspects. In short, many people are vexed by things like churches and prayer-books, and desire to reconnect with the wonder of ‘skies full of stars’ or ‘good feelings’.

Music is one way in which this can be done, and it really means connecting again with the inner self – that is, the esoteric. Coldplay might seem an unlikely messenger of some sort of revolution of the inner self. One begins to say that they don’t take themselves sufficiently seriously for that to be possible – and yet, the moment one thinks in that way, one realises that this is itself what frees people up. In Coldplay, a woman dreams of ‘para-para-paradise’ – and for many this brings paradise itself nearer than a Eucharist or a monk’s chant.

It would be a shame to miss out on all this in the mistaken belief that a song is a poem, and that a pop concert is meant to be an opera. Life isn’t like that, and I think we owe more to Chris Martin than many realise for not only knowing this but for enacting this knowledge.

Like this article? For more music content go to:

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ ‘Wild God’: ‘a song of planetary importance’

‘Steppin’ out into the dark night’: a review of Bob Dylan’s Shadow Kingdom