Christopher Jackson

Growing up is necessarily a provincial experience. It has to be: such a small proportion of the world is presented to us at that time. As a result, something like the following seems to happen: we come into the realisation gradually that our family’s experience of life, while it might be informative in numerous respects, also has to be a sort of red herring: we are not them and are not meant to be. Instead our obligation is to grow in some new direction in order to be ourselves.

What this all has to do with Stephen Fry I shall come onto in a moment. For now it is enough to say that predicament of youth can engender bafflement, even acute forms of anxiety. It was the novelist Sir Martin Amis who pointed out that nothing is so usual as what your father does for a living. He knew that from rich personal experience, his father being the equally famous novelist Sir Kingsley Amis. But many people have the opposite sense that one’s essential narrative might lie elsewhere. If this is one’s suspicion then what you badly need are clues as to what that might realistically consist of.

For me, growing up in rural Surrey in a good-natured suburb of lawyers and accountants, the existence of a group of comedians in the 1980s came as thunderbolts. Looking back, I realise they were also signposts. The moment I saw Rowan Atkinson on our TV screens as Mr Bean, and saw my parents crying with laughter, and felt the first true belly laughs I’d known rushing through my being, I felt a new scope rush in.

This must be a very common experience: here we are in our quotidian home, trying our best and seeking to be good; but out there, on the screen is another kind of life, which seems so hilarious, and so silly – and therefore somehow kind, and decidedly blessed. It is the world of celebrity and laughter. When we are young, it can seem like the most desirable thing in the world – full of high definition colour, and pitch perfect performance, a sort of paradise where outcome is in accordance with aim.

Of course what happens at that time in our lives is a broad revelation – what Philip Larkin calls ‘the importance of elsewhere’. It’s only later that you examine its particulars; how the sheer scale of possibilities relates to oneself. When I saw Rowan Atkinson terrified to dive off the top floor of a swimming board, I didn’t, as the world can now see, decide to be a slapstick comedian.

But I think I did decide around that time not to be an accountant. This decision was further crystallised when I saw John Cleese in Fawlty Towers, the frenetic clockwork pace of that sitcom, causing an escalating delight. It was shored up further by other experiences: French and Saunders, Smith and Jones, and later Harry Enfield.

But then there was another pair who spoke to me in a different way, and opened up, I now see, far larger possibilities: this was a pair of Cambridge graduates called Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie. Hugh Laurie seemed to me then – and still does – just about the most gifted person on earth. He is funny. He is a brilliant actor (see especially House). He plays piano, sings, and plays guitar beautifully.

Almost unnoticed, he is the best comic songwriter of his generation (‘I don’t care if people laugh/I’m in love with Steffi Graff’). His novel The Gun Seller is a delight. He was also responsible for A Bit of Fry and Laurie, my vote for the greatest sketch show of all time.

It was Laurie who made me pick up guitar and piano, and later write music. But of the two it was Stephen Fry who really interested me, and who pointed a more definite way. In this country, the trajectory is told everywhere from the life of Shakespeare to the novels of Dickens: you’ve got to get from where you are to London. And it’s from London that I write this.

What was it about Stephen Fry? It was partly because however troubled he was, he was so obviously kind – though over time I would find out that he could be rather hard on himself. But I don’t think it was primarily that. For me, it had all to do with his use of language, which came as the most wonderful and joyous surprise of my life. It seemed astonishing to me that people could speak like this, bequeath you a vocabulary as they made you laugh.

It was a form of proclaiming of themselves before the world – they could cause laughter in you while making you more intelligent. If you were receptive to it, it had to form you; Fry and Laurie made you want to be them, because it looked like an awful lot of fun. But not just that, it made you feel that if you could enter a little into their world, that you would know some special set of secrets. That way maybe you could build a life – one that was somehow true to a high set of possibilities.

These sorts of suspicions can only take you so far. Because pretty soon, life happens to you. As Mike Tyson beautifully put it: “Everybody has a plan until someone punches you in the face.” What happens is that life punches you in the face – and anyway, the world our heroes inhabits nowadays has so little to do with the one we end up entering. We specialise in the vanished paradise and the discarded Eden.

Nevertheless my preparations for a world which would have gone by the time I got there were unusuall thorough. I think I must have been 11 or 12, when my younger brother Tim – who would have been nine or ten – began learning and performing Fry and Laurie sketches to family and friends and sometimes to perfect strangers in restaurants. One particular sketch which we performed entailed Stephen Fry as a pompous late night talkshow host, talking on and on in the most preposterous way: “Is our language too ironic to sustain Hitlerian styles?

Would his language simply have run false in our ears?” My younger brother would play a baffled Hugh Laurie, who can’t understand what on earth the Stephen Fry character is saying. Amusingly, as I look back on it now, I had absolutely no idea what the language meant. This created a situation of considerable amusement when I performed before elderly relatives the following:

Language is my mother, my brother, my father, my whore, my mistress , my niece, my check-out girl. Language is the dew on a fresh apple. Language is a creak on the stair. Language is a ray of light as you pluck from an old bookshelf, a half-forgotten book of erotic memoirs.

I had no idea what any of it meant but I loved the music of it. It was the idea that language is a kind of music, that we can have fun with it, and play with it – and therefore, I suppose, that it has glorious function. It means that we can burst pomposity in this sketch, but of course, if you accept its use, then you must also admit that it can lead you onto new worlds. It can prise things open.

As I continued my studies in Stephen Fry, I found in him an educator – indeed, a sort of a remote and unpaid mentor. The power of this mentorship seemed to me no less important simply because he didn’t know who I was, and would almost certainly never know. This didn’t matter one iota so long as I was receptive and so long as Fry continued to build his career around the communication of the things he loved.

It is this love of things which I think defines Fry; it is a generosity in him which keeps spilling out. As I would go on in life, some people in the public eye would also give me great gifts. Amis, who I mentioned earlier, would give me Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov; Julian Barnes, whose books I could never get on with, offered up Flaubert in almost every interview he gave; Gabriel Garcia Marquez recommended me Virginia Woolf and Juan Rulfo; John Updike showed me Henry Green and so on and so forth.

It is perhaps the loveliest of all lessons for young people to know that in life, as in literature or art or music, there are a series of invisible threads to be grasped and which lead to pleasures you never could have imagined.

But Fry, I think, was different to all these people. He loved things loved so much that he had to enact that love. He didn’t just tell you in no uncertain times that he loved PG Wodehouse; he played Jeeves on television. He didn’t just love the novels of Evelyn Waugh, he directed a film of Vile Bodies, replacing it with the far better title Bright Young Things. And then there was Oscar Wilde, who he rather resembles, and who he often seemed to embody in his chat show appearances, and then on film in Wilde, the role which he was born to play, and which he played beautifully.

The world is a catty place and some would say that Fry has always been in some sense derivative. The argument runs that he has borrowed these personas and that there is accordingly some sort of gap within where the real Stephen Fry ought to be. The somewhat churlish columnist Peter Hitchens has called Fry ‘the stupid person’s idea of an intelligent person’.

I dislike this remark not just because he repeats it in print regularly with a kind of calculated cruelty, but because it isn’t true. Fry didn’t write The Importance of Being Earnest, it’s true, but he has done more than anyone to proclaim Wilde’s genius at his having done so. I don’t think Fry, clever as he is, has ever made gigantic claims for himself; others have done so, seeing his value. In time, the nation reached something like a consensus around this. They loved to hear him talk – but I think they loved really to hear him talk about his loves.

These seemed to have no obvious limit: in addition to Wilde, Wodehouse, and Waugh there was cricket, Paddington bear, nature, taxis, Abba, Sherlock Holmes, Ancient Greece, poetry, London, America. Really, we began to realise, he loves, or is capable of loving everything. This spirit, I note, is far closer to the Christian ideal than anything I have seen in the public domain written by Peter Hitchens.

Hitchens’ remark also lacks empathy. We now know what Fry was going through, and that he has suffered all his life with bipolar disorder which can lead him into manic moodswings; he has lived all his life with suicide as a realistic possibility. Here again, he has done more than anyone to raise public awareness about this health condition in his very important documentary The Secret Life of a Manic Depressive which aired in 2016, some four years before the pandemic when mental health really began to top the agenda.

His condition, which wasn’t widely understood at the time, was most obvious when Fry famously left the cast of the Simon Gray play Cell Mates in 1994. In the days before mobile phones, there was genuine worry about his whereabouts and the fear that something appalling might have happened to him. Gray was upset at the time that his play had been, quite literally, upstaged, and wrote about it at book length in Fat Chance (1995).

Nowadays, I doubt Fry would get to the end of his street without his whereabouts being broadly known; in those days, when he left the play mid-run, there was a genuine fear among his friends that he had vanished for good. Today, he is one of those people so famous, that he will never again be allowed to go missing.

If I were to compile a list of Fry’s dislikes, I feel I might reduce it to one thing: cruelty. His friend Christopher Hitchens has sometimes been called the hater par excellence, but I think Fry is a greater purveyor of dismay at human cruelty than Hitchens was, because, on the flipside, I think Fry’s kindness is more active.

The only kind of successful hate involves consistently pivoting to love, and my sense has always been that Fry is good at this. One early article which influenced me was his great defence of Freddie Mercury which is collected in his 1992 collection of journalism Paperweight, where – I am quoting from memory here since I can’t find the article online – he speaks of Mercury as having entertained with a ‘chutzpah bordering on genius’ and takes to task those who found his lifestyle immoral.

Its tenor was really ‘judge not less ye be judged’ – and again, one feels that Fry is always actively generous in spirit in way which ties in with the Gospels far more than one might expect from a man who shared the stage in religion debates with Christopher Hitchens.

His career grew in so many directions that it cannot easily be summarised. It has proceeded along novels (I especially recommend the first two The Liar (1991) and The Hippopotamus (1994), memoir (Moab is My Washpot (1997) may in fact be his best book) broadcasting (his best work here may be his brilliant hosting of the BAFTAS, which he did 12 times, finally giving up in 2018),

TV shows (Jeeves and Wooster, Kingdom), a marvellous poetry handbook The Ode Less Travelled (2005) which was instrumental in my ever publishing any poetry myself, as well as a host of illuminating TV documentaries, TV interviews, podcasts, blogs, posts, tweets and many other things besides. Fame is difficult to quantify but by any measure Fry is among the most famous people in the UK today.

My fame however is very easy to quantify: it is nil, and I am currently doing all I can to keep it so. However, just because I have ended up lucky enough to spend a lot of time carrying out interesting journalistic assignments, I must admit that it has involved meeting famous people of many different shapes and sizes all for the purpose of interviewing them. Some of them, from Sting and Andre Agassi to Sir David Attenborough, have been very famous indeed.

Some like Sir Tom Stoppard, Clive James and Sir Anthony Gormley have a mystique to those who mind about literature or art. Others aren’t famous at all to almost everyone, though they might be revered in their field. Out of all the categories of people I have come to most dread, I would single out those who are just a tiny bit famous as the ones to watch: amid the dim lights of that particular inferno, ego can be at its most pronounced.

At any rate, as you go through your journalistic career, you realise as you go on in your work that you are starting to meet your heroes. But even then, I never thought I’d meet Stephen Fry.

What exactly is going on psychologically when we meet our heroes? Dr Paul Hokemeyer, the brilliant author of The Imposter Syndrome, tells me: “Our fascination with and attraction to heroes is primal and hard-wired into our central nervous system. This is because heroes become like celebrities who occupy elevated positions of prestige and power in our society. From an evolutionary standpoint, we are instinctively drawn to people who will take care of us and from whom we can learn vital life lessons to protect us from dangers and advance our station in life. Because this draw is so primal and integrated into our central nervous system it often overrides our critical and rational thinking.”

In short, when you meet someone well known, we have a tendency to say stupid things. What is happening in the brain at such times? “As this relates to our neuroanatomy, being in the presence of a celebrity floods our central nervous system with a host of intoxicating hormones that override the intellectual reasoning found in our prefrontal cortex. Such disequilibrium causes us to say silly, often nonsensical things which place us further in a subordinate position to the celebrity.”

And how does this all play out from the point of view of the celebrity. Put simply, it’s not great for them either. “ Too often, however, celebrities become exhausted from the weight of this elevated and never-ending dependency. People become only able to see them as resources to advance their station in life.

They become like parasites sucking their life force and preventing them from finding any relational nourishment. In this regard, people become a source of danger and cause them a great deal of anxiety. This is one of the reasons why people of wealth, power and celebrity lead such isolated lives. They lack not just a circle of peers but also people who they can look to for nurturance and protection.”

What seems to happen is that a journalist – just by virtue of what he does for a living – comes into in a slightly different position when it comes to the famous. It might be that someone who isn’t battle-hardened when it comes to the sheer oddity of celebrity will meet someone, and the encounter may go badly because they will end up saying something just a bit odd in order to impress, or to draw attention to themselves. They feel the gulf between the famous person’s fame and their own obscurity too keenly and end up drawing attention to it.

The famous person, who will be by their position, extremely experienced in this sort of mismatched encounter, will sometimes try to amend the awkwardness but at other times they won’t. This might be personal (they’re tired and/or having a bad day) or it may just be that the encounter cannot be rescued. The famous person may then resign themselves to the thought that maybe it’s just easier to spend time with other famous friends. Almost always when someone moans that so-and-so in the public eye isn’t pleasant to meet I suspect that there will be some element of this completely understandable lack of expertise which has intervened on the encounter and spoiled it.

What’s interesting is that the way to remove the awkwardness of the encounter is not to care at all about fame, but to care about the person in front of you. This is not to say you should pretend they’re not famous as that would be to deny reality, but to treat fame as perhaps the least interesting thing about them.

Sometimes I have seen, in the middle of an interview with someone known, the person themselves, and there one sees something deeper and truer which has nothing to do with the construct of celebrity, though it will also almost certainly give clues as to why that person was driven to become well-known and also why the public reciprocated that wish. I am not saying that I am a master of this art.

I would not expect myself to behave with absolute equanimity if Elton John were to knock on my window as I write this, and offer up a private concert in my living-room. But it is what journalism teaches you, and it amounts to something like an inherent lesson of the profession.

Hokemeyer explains: “What such a person is doing is modelling humanity. By pre-empting the biological calibration that occurs around the power dynamics inherent in a celebrity identity by engaging in your intellect and rational mind, a journalist is levelling the playing field. You pre-empt the hijacking of your intellect by grounding the relationship first in the prefrontal cortex and then allowing your central nervous system to catch up. For most people, the calibration of psyches occurs in reverse. The central nervous system leads. Too often the intellect never catches up and the relationship becomes fuelled by unrealistic fantasies and harmful stereotypes.”

Quite by chance, on the 27th July 2023, I presented myself at the Oval Cricket Ground at the Micky Stewart Pavilion. I had, to put the matter as politely as possible, more or less had my fill of famous people. I am anxious here not to sound tiresomely world-weary since I have always been mindful of my luck in terms of meeting so many interesting people. However, it would be wrong to omit the fact that the encounter between famous person interviewee and non-famous interviewer is always on some level a sapping one, for the simple reason that by creating fame, and especially televisual fame, we have plainly released a set of completely crazy energies into the world.

I wave my ticket at the security people, a piece of paper which conveys the unlikely, but true, story that today I happen to be attending the final test of the Ashes courtesy of the Duchy of Cornwall. Instead of the interrogation I half-expect, I am waved through to the Oval, scene of some of the great climaxes in Test Match history. Here in 2005, Kevin Petersen hit his magical 158, with Shane Warne bowling his heart out. It is also a place of significant goodbyes.

Here it was that Alistair Cook scored 147 during his final innings having been short on form. Here too Don Bradman was famously bowled for a duck, when needing just four runs to end with an average above 4. Unknown to me, in a few days’ time, Stuart Broad will retire from international cricket having hit a six from his last delivery and a wicket with his last ball.

Inside, all is cricket lore – a lesson in black-and-white pictures and old news clippings about the history of cricket. The Oval is a place where time is prised open a little, and you feel a sense of cricketing history. Perhaps it is more forceful in this respect than Lords, because the so-called Home of Cricket is always cumbrously reminding you of its importance. Here the past seeps in almost casually.

I walk up the stairs and am asked to find my name on the guest list and sign in. As I scroll down the second page, I glimpse the names on the guest list: Sir John Major; Sir Trevor Macdonald, Chris Tremlett. My name must be on the first page, and there just down from my own, it reads: Stephen Fry.

I am given a name tag and move through to the bar area. Now, it is important to convey a little about the Micky Stewart Pavilion. As I understand it, one of the most interesting things about becoming the Prince of Wales, and thereby coming into the possessions of the Duchy of Cornwall, is to discover all the things which one suddenly owns. One of these possessions is the Oval Cricket Ground.

This means that if by some curious chance one is invited to the Micky Stewart Pavilion you are there to some extent because the Prince of Wales doesn’t mind you being there, or hasn’t noticed, or in my case, by a stroke of good fortune. In such places there is curious sense that everybody assumes you have some sort of validity just by being there at all.

As I walk in Sir John Major walks by and, ever the politician, he reads my name badge and says: “Hello, Chris, it’s good to see you here.” We talk briefly about the great sadness of the weather-affected draw the week before, which certainly have meant we’d be coming into this match with the scores level at 2-2.

I am always struck by the charm of senior politicians; I wasn’t able to vote in 1997 when Major was last on the ballot, but he has secured my vote retrospectively. We sit down for the opening session, and sit away from the bar in the stands. It only occurs to us once we have sat down that the green seats nearest the bar are for everybody to sit in. We might just as well, had we had the inclination, sat next to Sir John.

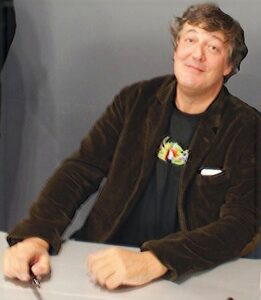

But what is the proximity of an elderly prime minister compared to a good morning’s cricket? Australia chose to put England in, in the justified belief that overcast conditions would make the ball swing. However, England put up a spirited performance, led by a swashbuckling 85 by Harry Brook. As we head inside to the pavilion for lunch, Fry is seated next to the door and smile congenially at us – he looks like someone who, should the moment arise, wouldn’t mind a conversation.

We head inside and there is a bit of mingling before lunch. Chris Tremlett towers above the company, looking like he could still take a wicket if suddenly summoned down to the pitch. By accident I find myself chatting to Fry, and I mention to him that my grandfather had grown up in the same village as him in Booton, in Norfolk.

“Booton!” he cries, delightedly. I can see how much he enjoys saying the word – which is, indeed, rather fun to say now I think about it.

I add that my great-grandfather was the rector of the church there. “Oh, I remember that cold church,” he says. “Were your family the Fishers?”

I say they were the Jackson.

“Ah the Jacksons!” he says, cheerfully, though I suspect that he can’t remember them and they may have been before his time.

After lunch, we head out and find Fry sitting alone on the green seats, and in a moment of curious madness, decide to sit next to him. It is worth saying at the outset that a good place to meet your hero is at the cricket: the rhythm of the match can interweave with your conversation, and it is less adversarial than the typical interview.

Early in our discussion, we talk a bit about our favourite Australians and I mention Clive James, who Fry knew well, and who I interviewed once towards the end of Clive’s life. I mention that I liked his poetry and that I was due to talk to him about The River In the Sky, one of Clive’s last publications. “Yes, I rather like Clive’s poetry too. He was a very good poet – when he wasn’t reading the whole of Western literature.” I mention that I was invited to Clive’s house for the launch of the book when I had committed to a press trip. Fry sympathetically winces: “That’s unfortunate.”

We then discuss Sir Tom Stoppard and I mention how kind he had been to me when we interviewed him for this magazine. I say it is often difficult to know how much one should thank someone well-known. “Oh, you always should. Christopher Hitchens always used to say that – thank your heroes.”

Does he miss Christopher Hitchens? “Hugely.” I ask him if Hitchens would have supported Trump or Clinton in the 2016 General Election. “It’s a well-framed question,” he smiles, “as if there was one thing for sure about Christopher it’s that he absolutely loathed the Clintons. But Trump? I think that would have been a step too far.”

He then tells me a lovely story about Tom Stoppard at a cricket match which Fry attended. The party were discussing collective nouns – a parliament of birds, a pride of lions and so on – when Harold Pinter and Stoppard walked in. Fry wondered aloud what the collective noun for playwrights would be and Stoppard immediately replied: “A snarl of playwrights.”

We discuss Leopoldstadt, Stoppard’s most recent play, which Fry has just been to see in New York. He asks if I have seen it and I say I have only read it but that the ending affected me deeply. Fry is wistful, no doubt thinking of the extraordinarily touching end scene, which I shan’t go away here: “Yes, I wonder what it would be like only to have read it.”

Stoppard, Fry recalls, used to play cricket for Harold Pinter’s XI. “It was called The Gaieties which has to be the worst name for an XI of all time – and not a very Pinteresque name.” I recall to him an essay in Paperweight that he had written an essay on chess and playwrights, and how the story of styles in the 20th century theatre mirrors chess-playing styles around the same period. “Well that’s just the sort of pretentious stuff I would write.”

I have throughout a sense of Fry which is rather touching. That is, even here, when he doesn’t need to be a performer. One senses the need to be loved, and that he is therefore always moving to make life easy for you in conversation – to make sure you’re at ease.

Down on the pitch, Stuart Board, I note is trying to anger himself into greater pace, and this prompts a discussion on the importance of anger in fast-bowling. ‘Bob Willis is the great example there – he always bowled better when angry,” says Fry. He also quotes Mike Brearley: “Anger always brings presents.”

As we talk, Fry explains that he is trying to do more to carve out time for the cricket, and that it was part of his motivation. “I have a lot of difficulty saying no,” he says, “which is why this summer has been so lovely.” It has been a time to pause work and spend some time with friends. “Hugh loves the cricket – he came along for a day,” Fry says.

Talking of fast-bowling greats turns us inevitably to Shane Warne. I ask him if he’s read Gideon Haigh’s great biography of Warne, and Fry is enthusiastic. Fry has also a kindly way of finishing your sentences for you as a way of making you feel you are being listened to and understand. When I begin to say there have been times when I’ve considered getting a subscription to The Australian only to read Gideon Haigh, I find that Fry has said the last five words on my behalf. Did Fry get to know Warne? “Yes, I did a bit – a lovely man.”

But of course you realise that however many people you might have met, Fry has known everyone. It comes with his position. Since we are here thanks to the Duchy of Cornwall we briefly discuss the Prince’s disinterest in cricket as opposed to football, Fry frowns in a comic way: “Well, yes, I have known for some time that the Prince is not especially interested in cricket. Prince George though when I saw him last talked of having ‘just been in the nets’ so perhaps things will be somewhat different in the next generation.”

It is a lovely thing to let the conversation as the cricket changes. At one point, Fry jokes about Todd Murphy, the Australian off-spinner. “Well, he’s got the off break, and then there’s also the off break. And if that doesn’t work, at least he’s got – the off break.”

At another point, enjoying the batting, I mention John Arlott’s description of Jack Hobbs, as what having made him great was his ‘infallible sympathy with the bowled ball’. Fry repeats it: “Oh Arlott! An infallible sympathy with the bowled ball. Marvellous!”

There is time also to reminisce. I mention how Fry and Laurie caused me such delight as a young boy, and even tell my story of reciting his work as a boy, and not knowing what the words meant. When he asks which sketches we used to recite, I tell him: “There’s this sketch where you play a pompous interviewee on late night television. “ “Sounds like me,” Fry says swiftly.

When I recite the sketch for me, I am able after all these years to thank him for it. To my astonishment, I see he is visibly moved to have had this impact. “We didn’t know the effect back then – it was like dropping a coin into a well. Every now and then with Fry and Laurie someone would stop you in the street – but it was very occasional indeed.”

I had heard a story of Paul McCartney, which I mention to Fry. Apparently, when he seeks to hire someone he always gets his driver to befriend someone lower down in the organisation he wants to hire, so as to be sure that they’re kind to their subordinates. “Did you ever get to know David Tang?” Fry asks and I admit I’ve never heard from him. “I loved him he was an incredibly kind man. But he could be extraordinarily rude to his subordinates. On more than one occasion he was David was so rude to his driver, that I had to get out of the car.”

As the often continues – and it was one of those rare giddy days in Test match cricket where wickets fall at regular intervals – I also get the opportunity to thank him for The Ode Less Travelled, his poetry handbook, without which I never would have been able to publish my own poetry books. I tell him his, and I also add that the poet Alison Brackenbury is an admirer. He is thrilled by this: “Alison Brackenbury! Well, I love her poetry so that means the world to me.”

Later I mention this to Alison and she replies: “How wonderful! We never know where our writing goes. I do think Stephen must be fantastically well-read to have found my poems. I have tried hard over the years to scatter them in the most unlikely places, but I doubt if even the amazing Mr Fry ever read the now defunct Tewkesbury Advertiser.”

I remind Fry that he says he writes poetry in The Ode Less Travelled, and tell him I think he should publish a volume of verse. He says: “Well, I did think during lockdown that I ought to compile that and I began it, but then I stopped.” How long would it be? He smiles: “Well that would depend on triage. Most likely it will probably have to wait for my will and then everybody will say: “What on earth was he thinking?”

The afternoon drifts on, cricket always intertwining with talk. At one point Fry jokes that we must ‘avoid clichés like the plague.” He talks of his admiration of Rowan Atkinson (‘no one else can convey a line like him’). He spends some time on cricket trivia, reminding me, for instance that Alan Knott wasn’t a wicket keeper at first but a bowler – and that being so good at the latter craft helped him become so brilliant at the former. His beloved Wodehouse gets a mention: “Wodehouse was told that he was most read in hospitals and prisons and first thought it a bad thing but then decided there could be no greater compliment to an author.”

And now I’m afraid I must go and do a talk in central London. He turns to me and says: “You’ve made an old man very happy.”

And then he’s off – having made me happy too. But the curious thing is I think he means it – and I wonder about the isolation celebrity must bestow. Hokemeyer tells me: “Occupying a rarefied position in the world is incredibly isolating. There are very few people who can look through the celebrity veneer and see the human being who resides below the power and sparkle that defines a celebrity identity.” Later I think back to the look Fry gave us as we walked past him – it was the look of someone who wanted conversation.

Do we perhaps all to some extent suffer from Imposter Syndrome? Hokemeyer explains: “Many celebrities, including male celebrities such as Tom Hanks and Ben Affleck have spoken publicly about their struggles with imposter syndrome. This is because attaining the status of celebrity on the scale that they have is akin to winning the lottery. It’s nearly an impossible goal that comes to too few. Being such a rarefied existence, their central nervous system can’t quite integrate it. As such, they live in fear that they will fall from grace and become irrelevant.”

I don’t think this will happen to Fry, but his charm seemed to be something allied to a sort of need: I don’t think it can be external approval which he is seeking, or external love even, since he has both in such abundance. It is internal, and I think fame and celebrity have a terrible way of wreaking havoc with that. Yet who could be better to watch cricket with? They say don’t meet your heroes. In general, I’d agree with that – unless your hero happens to be Stephen Fry.

Stephen Fry Education Timeline

24th August 1957 – Born in Hampstead, but grows up in the village of Booton, Norfolk, having moved at an early age from Chesham, Buckinghamshire, where he had attended Chesham Preparatory School.

1964 – Attends Uppingham School in Rutland, where he joined Fircroft house and was described as a “near-asthmatic genius”.

1973 – Expelled from Uppingham half a term into the sixth form, and is moved to Norfolk College of Arts and Technology, where fails his A-Levels, not turning up for his English and French papers.

1977 – Despite a brief period in Pucklechurch Remand Centre after stealing a credit card from a family friend, he passes the Cambridge entrance exams, and is offered a scholarship to Queens’ College, Cambridge, for matriculation in 1978, briefly teaching at Cundall Manor School.

1978 – At Cambridge, he joins the Footlights, where he meets Hugh Laurie and Emma Thompson among others.

1981 – Wins the Edinburgh Perrier Award for the Cambridge Footlights revue Cellar Tapes

1986 – The BBC commissions a sketch show that was to become A Bit of Fry & Laurie. It runs for 26 episodes across four series between 1989 and 1995. During this time, Fry stars regularly as Melchett in Blackadder.

1995 – Fry is awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (LL.D. h.c.) by the University of Dundee.

1999 – Awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Letters (D.Litt. h.c.) by the University of East Anglia

2010 – Fry is made an honorary fellow of Cardiff University,[148] and on 28 January 2011, he was made an honorary Doctor of the University(D.Univ. h.c.) by the University of Sussex, in recognition for his work campaigning for people suffering from mental health problems, bipolar disorder and HIV.

2017 – The bird louse Saepocephalum stephenfryii is named after him, in honour of his contributions to the popularization of science as host of QI.

2021 – Fry is appointed a Grand Commander of the Order of the Phoenix by Greek president Katerina Sakellaropoulou for his contribution in enhancing knowledge about Greece in the United Kingdom and reinforcing ties between the two countries.

For more of our cover stories, see these links:

Exclusive: how Emma Raducanu changed the world of tennis

Exclusive: how Elon Musk is changing the global economy?