If you happened to be in Essex on a summer’s day in 1995, watching Maldon Cricket Club’s 10 wicket win against Bury St Edmunds, you could be forgiven for thinking that you were watching not one but two future England cricket captains opening the batting for Maldon. These were Alastair Cook (known to friends as Ali) and David Randall (known as Arkle).

Both were gifted batsmen; each possessed musical ability (Ali on clarinet; Arkle as a future founder member of Maldon band Soul Attraction) and Cook would later recall of his friend: ‘I will never be embarrassed to say he was the better player.’

But in reality you would have been right about only one of them. Sir Alistair Cook, as the world knows, would go on to captain England, and score more runs (12,472) than any other England player. Arkle developed cancer and died in July 2012 at the age of 27.

His death wasn’t the end of his story. Throughout his illness he never complained and continued to do the things he loved. Sue Randall, David’s inspirational mother, picks up the story of David’s last week: ‘David’s big wish was to go to Wimbledon. All the MacMillan Nurses and District Nurses kept telling us that it would not be safe for David to go here and there. But the lovely Willow Foundation had got him tickets.’

Sir Alastair Cook is one of many patrons who came to the aid of his charities during Covid-19. Photo credit: By Harrias – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10180837

How did Sue react? ‘That was the only time I got angry with anyone. When David was out with his girlfriend, I phoned the nurses and told them that if David did not go to Wimbledon, he would die disappointed and I thought that we should do everything possible to get him there. Worst-case scenario was he died on the way, but at least he would have known he had tried to get there. By that time, he only had weeks to live at best. It was a saga! But he got to Wimbledon, taken by his brother. He went on the Tuesday, was admitted to the hospice on Wed and died on the Friday.’

It’s a story which takes us to the heart of life’s cruelty. Yet at its centre is something that seems to work against all hardship: David’s optimism, and intense love of life.

Sue remembered the lesson his boy had taught her, and started the David Randall Foundation which aims to keep his spirit alive. The charity organises Great Days for those with life-limiting conditions. Sir Alastair is its patron. This is a charity with a message for our times that will resonate: as the world seems always to become more morbid, we need the spirit of David Randall like never before.

An Uncharitable Virus

We also need the charity sector like never before. Young people might perhaps wonder whether it’s a vulnerable sector, and even whether it’s as worth going into as it was pre-Covid. While it’s true that many charities find themselves financially vulnerable, and have been hastily furloughing like everyone else, in researching this piece we also had a sense of a sector determined to be upbeat where possible.

Many, of course, were feeling acute financial pressures and it was not uncommon to find confessions that the person who would usually handle our query had just been furloughed. But for those who were still active, Finito World witnessed in some instances an admirable heightening of purpose.

Variety – the Children’s Charity works predominantly with children with special education needs and disabilities by supplying medical equipment ranging from diabetes monitors to wheelchairs and specialist car seats.

Captain Sir Tom Moore became the face of charitable endeavour during the Covid-19 pandemic

Dave King, the charity’s CEO, admits that events in early 2020 caught him by surprise: ‘By the time we became aware of the level of impact it would have, the virus was escalating quickly. This left us little time to get things in place before lockdown began. It was a period of confusion.’ Uncertainty is often a greater strain on a business than definitely dire circumstances. ‘Once the school enclosure had been announced,’ King continues, ‘we found ourselves in a better position. We were able to become more effective in our response once we had clear direction from government about the impact on children’s lives.’

Variety began refashioning its processes. ‘One of our programmes involves grant-giving for specialist equipment for schools, and equipment for children,’ explains King. ‘We’ve managed to keep that running in spite of supply chains closing down and being temporarily suspended.’

This is a major achievement especially as it was delivered at a time when the organisation’s income generation fell dramatically, primarily due to the loss of events revenue. ‘You can’t have a gala dinner with just a few people in the room. The atmosphere will be flat and it won’t be worth the outlay,’ King says.

In sustaining itself, the charity was helped by its active golf society and golf memberships. These benefitted from that sport’s ability to be carried on while social distancing. ‘We’re looking at how we can maximise the use of our golf team and our society and to generate income.’

As difficult as these times are for generating revenue, there is something that can still pull in the money even over Zoom: stardom.

Stars in their Eyes

Variety has been fortunate in its celebrity ambassadors, with Len Goodman and Mark Ramprakash singled out by King for lending particular support to the charity.

This opens up onto the wider question of celebrity involvement in charities. Dan Corry, the CEO of Think NPC – a charity which supports other charities – argues that while having a well-known patron doesn’t always make a difference ‘it can definitely help. Anything you can do to put yourself in the limelight, and get people to open that email, or look at that tweet.’

Within the sector, there’s some debate over whether celebrity involvement increases the amount of money going to charities as a whole. Cory asks: ‘Does having a good celebrity or fundraising campaign raise money for your charity instead of one they would have given to? Does it just spread the money differently?’ A relevant example here would be Captain Tom Moore, who walked around his garden for NHS Charities Together. Cory says: ‘Some in the sector felt that people who would have given to a medical health charity gave to that. In aggregate, it’s hard to tell. Is it the right charity just because there’s a star celeb? It might be a rubbish charity.’

Even so, the charities Finito World spoke with are deeply grateful for the assistance well-known names had given to their charities.

Sue Randall says that Alastair Cook always comes through with ‘two tickets for the best seats’ at Lord’s for Great Dayers, adding that he ‘has never let us down.’ She adds: ‘Andy Murray also came up trumps for us last year. We had got a lady with cancer, some tickets for Wimbledon and on the day she was too ill to go. One of our ambassadors got in touch with Sir Andy and he sent her a personal note saying how sad he was she hadn’t been well enough to go, alongside a signed shirt. So he is now a hero to me!’

Meanwhile, Ed Holloway, Executive Director of Digital and Services at the MS Society, recalls how the charity was able to pivot quickly during coronavirus thanks to celebrity generosity: ‘One of the first virtual fundraisers we did [after the virus hit] was the MS Society Pub Quiz, with the support of our ambassador and BBC Radio 1 DJ Scott Mills, who hosted a virtual pub quiz every Wednesday night, live from his living room. It was an incredible way to bring the community together at what was a very difficult time. Not only did we have thousands of people all playing along for a great cause, we had a lot of fun doing it, Together, we managed to raise an incredible £55,000.’

In July, I zoom with Gruffalo and Zog illustrator Axel Scheffler who has had longstanding involvement with the National Literacy Trust (NLT), an independent charity committed to improving literacy among disadvantaged groups. When the pandemic came along, he was happy to help.

He talks to me in his studio, with books ranged behind him, which themselves cede to a bright skylight. Softly spoken and matter-of-fact, it is clear that his charitable work is conducted out of a quiet and laudable sense of duty. ‘I have said yes to almost 95 per cent of what I’ve been asked to do,’ he says, in his careful German accent. ‘There was one job where a big airline company wanted me to design some airline masks and I said no to that one. Overall, it’s a difficult situation and we do what we can. I can afford to do it, and so I do it.’

Axel Scheffler has been highly active for the National Literacy Trust during the pandemic.

Early on in the pandemic, Scheffler was asked by the NLT to provide illustrations to an online book Coronavirus intended to educate 5-11 year-olds about the new disease. Published by Nosy Crow, and narrated online by Hugh Bonneville, it was publisher Kate Wilson who persuaded Scheffler to make time for a breakneck production schedule. ‘Her argument was that many children are familiar with my style and work, and that was why I said, “Yes, I’ll do it.” Nosy Crow completed the project from start to finish in 10 days: it was really, really fast.’

Scheffler explains his motivation: ‘I’ve supported the NLT for a long time, and it’s brilliant what they’re doing. I think it’s sad that a nation like Britain has to have a charity to deal with these matters. It should really be up to schools to get children reading and it’s sad the government is failing the education of children in so many ways.’ It’s hard to disagree but it’s also surely this which makes the charitable sector so exciting.

‘Nobody’s poor relation’

The CEO of the NLT Jonathan Douglas argues that there’s never been a better time to go into the charitable sector: ‘Its vibrancy and its entrepreneurial ability comes from the fact that its funding base is always tenuous.’

Paradoxically, Douglas explains, it’s been a good time for the sector, in spite of the challenges: ‘The most heartening thing without a doubt has been the organisations that have come through to support shielded people, support children continue learning, and to support the victims of domestic abuse. All those social needs have been met by the charity sector. I don’t think the charity sector could ever have been written off as inconsequential – but after the way it has stepped up in the past three months it’s proved its mettle. We’re no longer anyone’s poor relations.’

Over at the MS Society, Ed Holloway continues to feel the sector is attractive: ‘Like many charities we are relatively small and we ask a lot of our employees, but this gives them a chance to take on responsibility early in their careers, which stands them in good stead for the rest of their working lives. In return for their hard work and commitment, we work hard to provide a stimulating workplace where everyone can engage with our mission, know their voices are heard, and know they are making a difference to people living with MS.’

Even so, that doesn’t mean that life is always easy. King says: ‘Most charities are operating on the frontline. The more we’ve got in the bank the less we’re helping kids.’

Government response

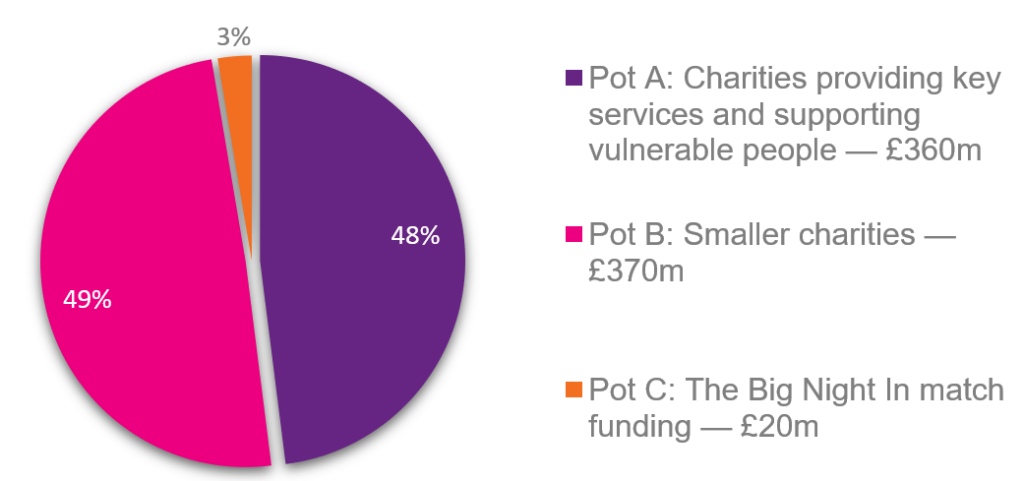

On April 8th 2020, the Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced a £750 billion package ‘to ensure [charities] can continue their vital work during the coronavirus outbreak’. Figure A shows where the money went. Unfortunately, in many cases it didn’t go far enough.

The picture is complicated by the fact that it is often difficult to tell what sums charities may have received from independent grant-making foundations such as the Esmée Fairburn Foundation and the Lloyds Bank Foundation. In some cases, there will have been overlap, although that can be difficult to unpick. Cory says: ‘When this crisis is over, I hope we realise that we need more data in this sector.’

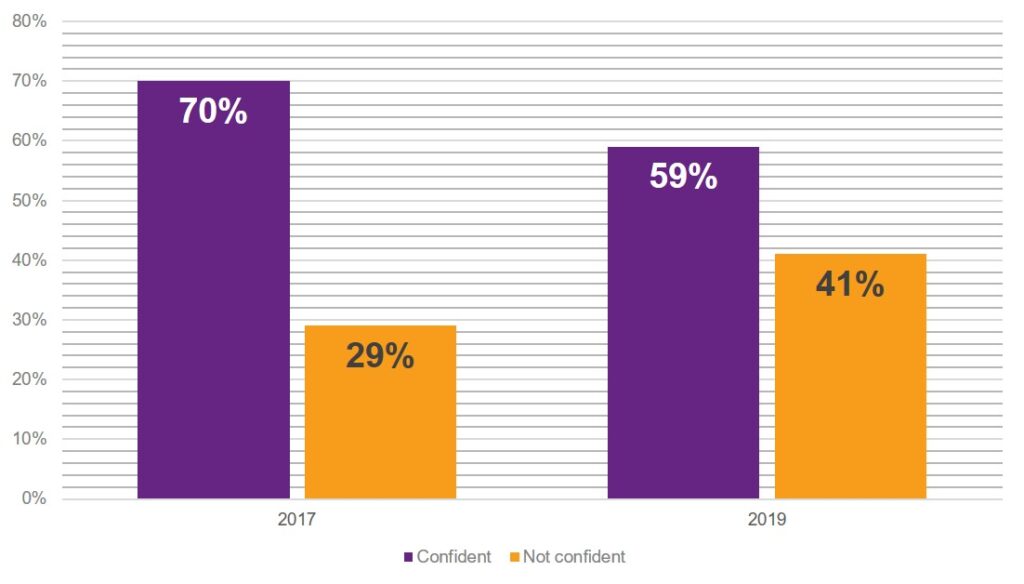

Here charities were asked whether they were confident they were making the best use of digital. Credit: Think NPC

King argues that government announcements were ‘targeted at organisations already delivering government services,’ adding, ‘we don’t receive any help whatsoever.’ A few weeks after speaking with King, Finito World heard that he too had been furloughed.

Large charities like the Family Fund received large injections of cash; other smaller organisations did not. But even at the top end, there is pain. As Dan Cory says: ‘For the big charities, a lot of funding came from big events like the London marathon. Almost all of that has been kyboshed.’ With furlough now about to wind down, many charities including the National Trust, and Cancer Research UK have already talked about redundancies. In some cases, charities that relied on gift shop income have suffered, Cory explains: ‘They have no income. People aren’t rushing to the shops. They’re usually the kind of shops we like rummaging in, but now you’re not meant to touch product.’

ThinkNPC also argues that the Treasury’s monies – though ‘pretty generous’, according to Cory – even at the high end’ A recent report by the organisation found that 27 of the largest service-delivery charities in the UK faced a ‘£500 million shortfall’. The report also found that ‘charities fulfilling contracts for local and national government are better insulated, whereas charities who rely on public fundraising and charity shop trading are far more exposed to more significant losses.’

Ed Holloway told us about the gravity of the situation regarding MS: ‘The MS Society faces losing nearly a third of our income this year due to Covid-19, and yet we haven’t received any support from the Treasury’s £750 million funding package for charities.’ What matters here is the centrality of the society’s role in the fight against an awful disease: ‘The MS Society is the UK’s leading not-for-profit funder of MS research, and every year we invest millions in new projects – so sadly MS research is one area that has been affected by this shortfall. With researchers redeployed and labs closed due to social distancing, the pandemic had already affected many of the vital projects we fund. Right now, we’re doing everything we can to keep these going, but this significant loss to our income means planned research must be postponed, and we are unable to fund promising new work that is desperately needed.’

When we wrote to the Department for Culture, Digital Services, Media and Sport to ask whether some smaller charities were falling through the cracks, we received no reply. Cory says: ‘My guess is medium-sized charities – in the £1-5 million bracket – have been suffering a lot. For the smaller ones, it’s difficult anyway. Typically, at a small charity you have two and half people with volunteers. Quite a lot aren’t going to survive this but it’s always like this down that end of the scale.’

As grim as this is for many, if one were minded to be optimistic about anything at the moment, it would be about those who work in this difficult but noble sector: Variety which continues to send vital equipment to children; the NLT, which is more committed than ever before to literacy in areas that need it; the MS Society, which is still a beacon of hope for those suffering form an inexplicable diseases; and the David Randall Foundation which remains committed to making people’s last months and weeks memorable.

In my most recent email from Sue Randall, she tells me: ‘Things are still very slow with DRF. Understandably the people we organise days out for are vulnerable and nervous about going out, but requests have started to trickle in. The trouble is you just start to think it’s Ok to go out and then the government starts bringing in more restrictions, so I am not surprised at people’s reticence.’

This is a view in miniature of the sector as a whole: a sense of duty overriding anxiety; a sector which has been knocked which remains determined to rebound; and above all an industry with an ethos which values doing things not because they are intrinsically commercial, but because they are inherently important.

Will it all come back? Cory is cautiously optimistic: ‘Not in the same configuration. But people’s will to do good and get involve in charities to work for them or volunteer is pretty undiminished.’ In these times, we must take the positives where we find them.