by David Hawkins

When I was at university (Durham 1993-96), the prevailing trend was to apply to accountancy, the law, management consultancy or banking.

Whilst I didn’t immediately enter the world of finance, I am quite unique in the “wealth” and family office space in that I started in politics and government relations, with a sojourn in PR, corporate affairs and private equity before working for a HNW (high-net-worth) family for their philanthropy, reputation and business interests – effectively establishing their family office in London.

I’m not sure what those of us applying for “banking” were really thinking what the career would constitute, investment banking sounded so grown-up, alpha-male, “greed is good” and en vogue (the mid-1990s saw a huge consolidation of investment banks and the end of “merchant” banks).

Private banking and wealth management in contrast seemed distant, purposely opaque and a bit stuffy. It wasn’t an attractive career option because it didn’t really care to explain what it was.

Wealth has to be managed – that is the focus of wealth management – and with this term I mean a form of investment management and financial planning that provides solutions to clients with £1 million plus in assets or ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) with £30 million plus in assets.

It is a discipline which we can also call private banking and which includes financial planning, investment management, tax planning, luxury assets and some other services such as corporate finance and investment banking. It can also extend to trust companies who hold assets and even the private client law firms who advise, structure and act to protect the wealth of their clients.

So breaking this down, it can offer a career as a financial planner – working with clients on their strategy for wealth preservation and growth: which can include retirement planning, tax, legacy and succession and business planning. Once this wealth strategy has been devised, an investment manager then works day-to-day to deliver returns that the client and their planner has objectified. Tax planning is a third role and is vital as the tax implications for a HNW – whether dividend, CGT, inheritance, corporation tax or cross-border tax – can be huge. As HNW’s purchase luxury assets – houses, jets, yachts, art – these need managing, financing and servicing.

When HNW’s need support in their business ventures, wealth teams often bring in their respective corporate finance teams of their institutions to support clients in corporate objectives – eg financing a new factory or the acquisition of a digital business. A trust company holds assets on behalf of an individual, family or business – generally to minimise tax but also to reduce other risks and acts according to a constitution which has been agreed on behalf of the various beneficiaries.

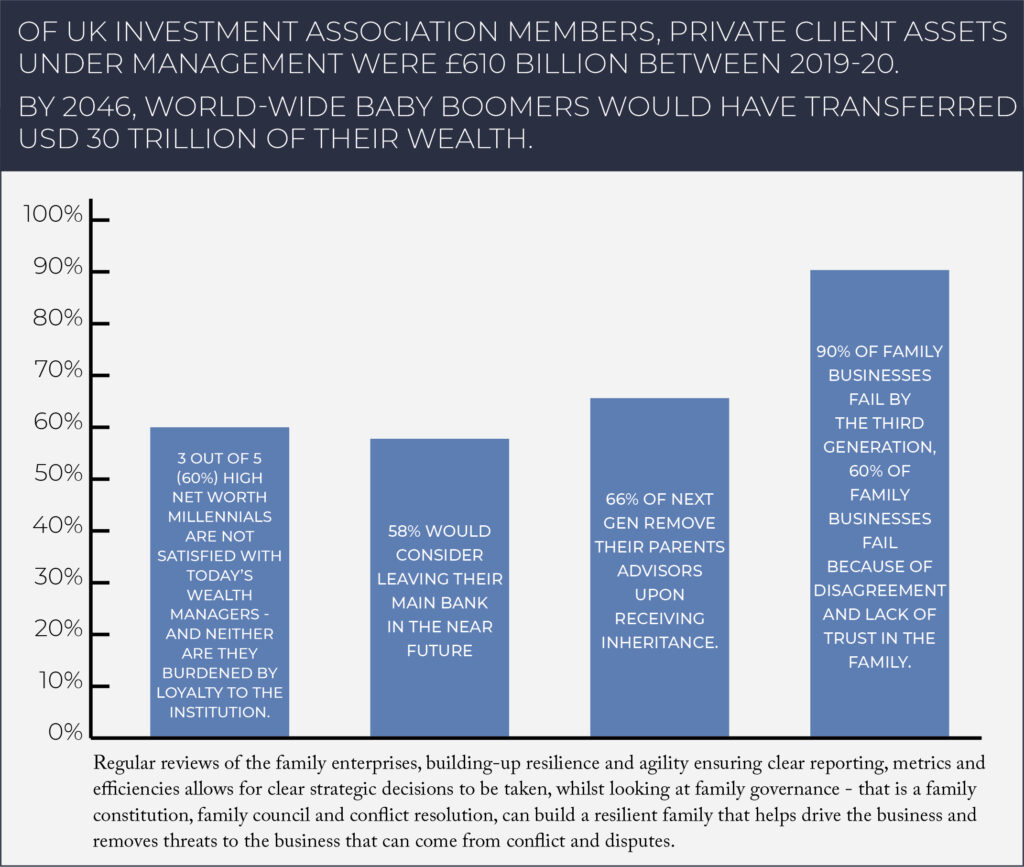

Changes have come, but a lack of trust in banks and the wealth sector has driven a long-term move amongst the very rich (UHNWs) towards family offices. The ongoing criticism of private banking / wealth management is the high turnover of staff, that the investment manager operates in his (or their) own interests rather than always for the client, and they were increasingly limited by compliance from suggesting entrepreneurial solutions that suit the client. This has been further aggravated by the fact that clients themselves have been changing: the values of the rising next generation in particular have not been mirrored by their advisor, whilst clients want more bespoke products that banks struggled to keep-up with.

All these factors combined have been the catalyst behind the rise of the family office, a privately held company that handles investment management and wealth management for a wealthy family, with the goal being to effectively grow and transfer wealth across generations. They also have impacted the less affluent as we shall see below.

To be an effective single-family office handling your own family’s investment requires a significant sum of cash as staff costs and compliance costs can be very high.

The definition of a family office can differ from one family to another – a family office advisor once wrote that to be a real family office – similar to the archetypal established by John D. Rockefeller – one needs to follow the APPLE model: investment should be Active, Passive, there should be Philanthropy, Legacy-planning and Estates-planning.

Family offices may also handle tasks such as managing household staff, making travel arrangements, property management, day-to-day accounting and payroll activities, management of legal affairs, family management services, family governance, financial and investor education, coordination of philanthropy and private foundations, and succession planning.

Sometimes families combine costs and can be structured as a multi-family office – professional staff representing a number of affluent families and individuals, often creating their own co-investment products.

Given the very discrete nature of family offices, they are very hard to apply for internships or work – however multi-family offices: Stanhope Capital, Schroders Global Family Office Services, Stonehage Fleming are easier to identify and approach for jobs.

One of the key areas affecting recruitment into the wealth sector is the widening gulf in values between the rising next generation of clients and their existing advisors.

Millennials1 and Generation Z2 have a series of values that has fundamentally shifted from the generation above them. They are a more socially-conscious generation which seeks businesses that mirror their values, are digitally enabled and allow for ease of use.

From this arises two distinct problems for the wealth industry. Firstly, the recruitment of the next generation of staff – when most smart graduates would rather go into a tech start-up, the wealth sector is not selling itself effectively. Secondly, how does the wealth sector engage the next generation of HNWs, the clients of tomorrow, when their staff don’t immediately mirror the values and thinking of their clients?

In their study from 2019, pricing consultants Simon Kuchner & Partners surveyed almost 650 high net worth millennials worldwide from six countries (Australia, China, Hong Kong, Singapore, the UK, and the US) to examine their attitude towards private banks and wealth management.

The report found that all of the participants had at least one private banking relationship in the family and/or at least 500,000 US dollars of investable assets in their personal accounts, with a significant portion of the wealth being inherited from the previous generation.

The study also found that 60 percent of millennials were dissatisfied with their present banking and wanted a substantial improvement. The survey found that to attract future customers and build ongoing relationships with millennials, private banks have to comprehensively analyse their processes, assess their current shortcomings and potentially re-build a new bank from the ground up even if this means taking short-term losses for sustainable long-term profits.

There were other findings. Private banks also need a fundamental new brand position – old, male, pale and stale won’t cut it anymore – diversity is key and having staff that reflect the new client is key.

So private banks need to act fast and develop a ‘WOW’ digital ecosystem that highlights self-service capabilities or they risk becoming irrelevant. Millennials want the option of immediate and bespoke banking services – even so far as online bespoke investment and portfolio choice. To attract this generation, banks have to reposition itself as a millennial-centric bank and highlight the values that millennials look for, which according to the Simon Kuchner & Partners survey is quality and brand.

A number of banks have been developing their next gen offering, whilst some of the larger MFOs have been active to. But more needs to be done clearly define why millennials should pay for their financial advisory services. With a clear value proposition outlining what private banks and the wealth sector can offer, millennials are willing to spend more on financial services.

If the wealth industry moves quickly it can meet the challenges outlined above: reduce its opaqueness, become digitally-enabled and truly bespoke and so attract the next generation of clients but also of staff.

____________________

David Hawkins is the Founder of Percheron Advisory, a firm which works with entrepreneurs, HNW clients and business families with a focus on building resilient and agile operational business frameworks and developing effective family governance structures.