This letter is ten years late. I went to Israel for the first and so far only time in 2013, and for obvious reasons have been thinking about the country a lot since the attacks on 7th October 2023, and the events which followed. This is really a letter to Israel – a delayed epistle I’d been waiting for an excuse to write.

I was unlucky in the lead-up to that trip: I dislocated my knee playing tennis a week before flying. I was thus forced to cut a comic figure in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, hobbling with my grandfather’s old silver cane around the Old Town, which, as visitors will know, contains numerous steep pathways, including the famous Via Dolorosa up which Jesus is meant to have shouldered his cross. At one point, I remember an eight-year-old girl trying to steal my cane off me, leading to a scene reminiscent of the sort of thing which might happen to Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm, where I sought to wrest it back and found myself only just equal to the task.

But I found I loved the country: loved its noise and its contention, and the passion for theology, philosophy and history that lay behind its disagreements. Jerusalem is a microcosm of the human story. To step into it – even casually, and unwittingly – is akin to presenting yourself to humanity for inspection. It all amounts to the strangest of looks in the mirror.

In Jerusalem, it’s not unusual to find people coming up to you in a bar and asking some variant of the question: “Who are you?” “Where are you from?” To ask this question in any other city in the world is to issue a pleasantry; in Jerusalem it feels deeper than that, an invitation to consider your personal identity. Most people who go to Israel end up feeling that they somehow needed the experience. At times, it feels like undergoing therapy.

It’s no coincidence that in the Gospels Jesus’ opening remarks to his disciples constitute both a salutation and a challenge: “What seek ye?” Quite a lot of the time in Jerusalem one closely neighbours the related question: “What am I seeking?”

The answer, if we’re honest, almost always involves some sort of large noun: truth, beauty, happiness, love, God – peace. Jerusalem is a place to consider all these things, although periodically, as on October 7th 2023, it particularly evokes the question of peace. That’s because that question: “What am I seeking?” hasn’t always summoned up the same answers in the hearts of human beings.

The large nouns mean different things to different people: for some happiness is a rave – for others it’s a church service. Peace in turn can be the means by which we gently seek to bring others into our sense of the world, or open ourselves to new avenues of being. Alternatively, as with Hamas, peace might almost slide into its opposite: it might masquerade as the means by which we seek to still a murderous resentment which all too readily rises up in human minds.

The founding of the state of Israel was widely deemed necessary in the aftermath of the Holocaust, but soon ran into a difficulty which now feels somewhat inevitable due to the geography of the situation. And yet if we believe at all in human freedom then we can’t quite throw up our hands and shrug that it had to be that way. We must admit that the whole question of the state of Israel foundered on human frailty.

As a general rule, wars are what incompetent governments inflict on unsuspecting peoples. We cannot call the period from 1948 a period of model governance. On the other hand, there have been periods of statesmanship: the Oslo Accords, begun in 1995, and the Unilateral Disengagement Plan in 2005 both amounted to attempts to move towards the solution of the problem.

As I travelled through Israel, I found myself asking how the situation has deteriorated so seriously so rapidly. The first clue is in the history itself. Everywhere else on earth, history feels asleep by comparison. Here, you feel its urgency – its pulse. To be surrounded by so much holiness is to exist in a highly alert moral condition, and this is the case if you’re only visiting. To live here must be another step up.

Secondly, I often think of an observation once made by Daniel Barenboim the c0-founder, with Edward W. Said, of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. This orchestra brings together Israeli and Palestinian musicians. Barenboim was at a rehearsal and stepped out for a moment, returning to find his orchestra at loggerheads over politics. He watched them argue and reflected that both sides of the argument are of a similar temperament. It isn’t, Barenboim reflected, like a conflict between the Swedes and the Italians. This fact alone, Barenboim says, accounts for much.

It all amounts to a charged atmosphere. There is a lovely museum Ticho House in Jerusalem which all visitors should see. It was founded by Dr Abraham Ticho, the husband of the landscape artist Anna Ticho. When Abraham, an ophthalmologist, was injured in the 1927 Palestinian Riots everybody – Jews, Christians and Palestinians – prayed for his recovery since he was the go-to man for the treatment of the common ailment trachoma.

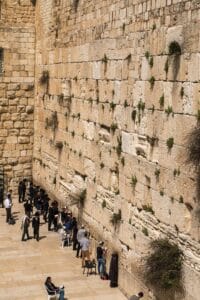

These riots, in which 133 Jews were killed by Arabs and 116 Arabs killed predominantly by Mandate police, were sparked by questions of access to the Western wall. It all reads like a terrible promo of the conflict we now have. The Shaw Commission, charged with looking into the matter, would find that the riots were caused by “the Arab feeling of animosity and hostility towards the Jews consequent upon the disappointment of their political and national aspirations and fear for their economic future”.

Of course, one might have feelings of disappointment and anxiety without resorting to murder, and Ticho’s story reminds us that many didn’t have these feelings. It is worth visiting the Ticho museum to remember not just Ticho, but the people of every denomination who prayed for him because his medical skill ensured he was part of their shared interest. In Ticho’s story, we receive a tantalising glimpse of another set of possibilities for the region which sadly has never yet been taken up.

And there is something unique about his wife Anna’s landscapes too. In these pictures, it is as if the land of Israel, like Jerusalem itself, carries a particular charge. This isn’t solely to do with politics: for Christians (and for many Muslims), these are the hills which Jesus retreated to in between sermon and miracle; for Jews, each bush can be aflame, as it was for Moses, with the suddenness of God; for Muslims, the very sky is open – filled with the idea of ascending to the Heavens. That means that Ticho can never be painting landscape in quite the same way that, say, Constable is painting landscape: she’s painting spirit.

Injured though I was, I decided it would be worth taking a taxi out onto the West Bank. In Bethlehem, you can visit the Church of the Nativity – the supposed original of the manger which we used to recreate in our youth in rural Surrey. As we drove out, I saw the grape sellers – all Palestinians – reduced to selling grapes on the side of a dusty road, where little traffic comes. All drivers know that non-dusty grapes are available in the supermarkets of the built-up settlements nearby. It is a hopeless situation and even those broadly supportive of Israel will wonder at a lack of humanity which is so evident but whose causes are so difficult to trace.

In Hebron, the look and feel is of a warzone without the bombs falling. Children kick bedraggled footballs against the walls of shuttered shops; Israeli tanks move through the streets, like sharks through a fish tank. Here the guidebooks point you to the Cave of the Patriarchs, considered to be the burial place of Abraham and Sarah – figures whose importance the major religions agree on.

Here one feels one is entering something like the crux of the matter. As a Westerner, I was only able to go in through the Israeli side. There is an entrance for Muslims I didn’t see, and the interior itself is partitioned. I hobbled up towards some Israeli soldiers who seemed to be mocking my injury in Hebrew, which didn’t strike me as the most welcoming start.

Inside, there is a seminary where Jewish students recite passages from the Torah, and everywhere there was a hushed seriousness and, to me at least, a palpable sense of things being about to kick off. This is the hard fact about Israel: from Woody Allen to Larry David, Jerry Seinfeld and Mel Brooks, nobody has made the world laugh harder than Jewish people. But to come to this land is to feel that everything keeps coming back to a flammable seriousness.

In that Shaw Report which I quoted a moment ago, the writers added that the cause of those 1927 riots was the Palestinian sense that Jewish settlers were ‘not only a menace to their livelihood but a possible overlord of the future.’ In 1927, some two decades before the founding of the state of Israel, this was remarkably prescient: for many Palestinians this is what did happen.

As you climb the hill to see Herodium, Herod the Great’s palace, I had a panoramic view of the homogeneous settlements somewhat resembling the worst kind of British council housing. As I hobbled skywards, the Adhan – the Islamic call to prayer – reached me easily from the skies. Sometimes it sounded like an assertion of some kind; at others a cry for help. Looking down on those towns from the archaeological site, everything felt so terribly boxed off.

A commitment to freedom of movement is what we still have here in Britain and in the UK: this in turn is built on trust and the notion that everyone potentially has something to contribute through hard work to the betterment of all our condition. Interestingly, if you had to pick a country in the Middle East which has some of this spirit, you’d also pick Israel, especially Tel Aviv with its superb food and Miami-like energy of expansive bustle.

We have all seen music festivals like the one which was taking place near Re’im on Black Saturday; most of us have been to them. These festivals, very far from my cup of tea, are part of our national life, and so we might recognise ourselves in the victims of the massacres. Alarmingly, I don’t think if Hamas were exported to the UK, that they would have much hesitation in massacring Glastonbury, as appalling as that might be to contemplate.

This, in turn, cannot help but generate some questions regarding the pro-Palestinian – and all-too-often pro-Hamas –marches on the streets of London. Firstly, how many have been to Israel? Secondly how many of them have been to Glastonbury? One suspects here a far higher percentage in answer to the second question than to the first. But if this is the case, then many are marching in favour of the very people who would murder them if they had half a chance.

None of this means that Israel has behaved in a flawless manner. Too often, violence has met with ratcheting language, and counterproductive violence. The failure is predominantly one of political leadership: no one would accuse Benjamin Netanyahu of too much resembling Nelson Mandela. But to consider this an isolated failure on the part of Israel’s leadership, as so many do, is a dangerous fantasy. To land on a fairly obvious point: any organisation whose central text is the Protocols of the Elder Zion, as is the case with Hamas, has a fair amount to learn about peace-making.

Some people need to be fought; there is such a thing as the legitimate causus belli. In addition, the Mandelas of this world have a far greater dose of realpolitik in their make-up than we realise when we later lionise their achievements in peace. We forget that they often pivot to resolution only after having defeated the harshness of their enemies. Hamas has never been as cuddly as the left-wing intelligentsia has liked to imagine it.

The reality is that history – any nation’s history – is peppered with injustices of every kind. The past is in some fundamental sense unthinkable – and yet it all happened.

The usual way in which we move beyond atrocity is by acknowledging that many evils were perpetrated by the dead. This is the basis on which we forgive and forget. In England, we no longer identify with a particular side of the War of the Roses; I am as welcome in Lancaster as I am in York. Except when a rugby match rolls round, we have also rather forgiven the Norman conquest – and anticipate, as we walk through Paris, a degree of forgetfulness regarding Agincourt. The past has to recede because it was conducted by imperfect people.

The same is true of the founding of Israel, and in relation to recent history in the region. There are two differences. Firstly, these events are closer in time. But secondly, the fear is that they shall in same way always remain so, because they revolve around both temporal and eternal questions. For so many people, Christianity, Judaism and Islam still matter, forming part of our essential hopes beyond the life of the body. It is not just that these affections won’t go away – it’s that anyone of religious inclination would be bereft if they did.

If you want to know what that would look like then you have Soviet Russia, and maybe the hard-left wokeness in the UK to sample: identikit moralities where power goes not to the meek, the thoughtful or even the hard-working but to the noisy and the cunning. That’s the real reason one suspects that a large chunk of the left marches against Israel: they don’t believe in any eternal dimension whatsoever and would like to delete that from their lives. Like Christopher Hitchens, they loathe religion full stop, and can’t distinguish easily between the book of Genesis and Hamas: to them, it can all be grouped under the ‘God is not great’ banner.

This is the intractability of the crisis: it goes deep into all of us and keeps refusing to recede. Israel is a remarkably complex undertaking with a paradox at its centre. It is, in one sense, a representative of the Western way of life in the Middle East. There are few cities so Bohemian as Tel Aviv. But, at the same time, when you get right down to it, it isn’t a particularly secular country. Too much of the Bible and the Koran takes place there for that to be possible.

These two aspects have both created enemies. The hard fundamentalist right dislikes its licence; the left dislikes the obligation it places on us to consider religion. Israel is a land of miracles and from one perspective the bar of not killing one another over a set of misunderstandings feels sufficiently low that it ought to have been achievable by now. But we have to admit that it hasn’t been and that if you ever go to Israel you’ll be visiting the saddest, but also the most necessary, place in the world. It’s not a foreign country – it’s our collective story and that’s why it will always matter.

For other examples of our letter series try these:

Discovering the Charm Budapest: Tom Pauk’s Letter from the Heart of Hungary

Omar Sabbagh’s Letter from Dubai: ‘As soon as it was safe enough to reopen, that was done’