Christopher Jackson

I’ve often thought that spring has its secret pitfalls, but in 2023, when the season turned, it seemed to have more than usual. Every time the moment of the clocks going forward comes round, I always think, remembering Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Beware the Ides of March.” And it was TS Eliot who wrote of April as ‘the cruellest month’ when the promise of spring cedes instead to rather a different reality.

So it went in 2023. I woke to Budget Day on the 15th March to what seemed on the surface good news: the government would extend the free 30 hours of childcare to those with children aged one and two. However, given that I have a daughter who has just turned three, this development put me in mind of the Philip Larkin couplet: “Sexual intercourse began in 1963/ (which was rather late for me)”. Many parents woke to news that the money which had essentially constituted a second mortgage was not money they’d have had to spend had they elected to have children a few years later. As Kurt Vonnegut put it: So it goes.

Even so, the policy won’t come in until 2025. While it’s not immediately clear whether a Keir Starmer administration would keep to a promise made by the other lot, the suspicion remains that he’d be hard-pressed not to. The policy is a generous one, representing a possible alleviation for many households where the incentive to work is dramatically reduced by the cost of nursery fees. When my daughter turned three, I filled out my forms with Southwark Council with the sort of passion and alacrity which, to put it mildly, I never attack my annual tax return.

I should add that the policy, announced by Jeremy Hunt, also represents a personal triumph for the brilliant MP for Stroud Siobhan Baillie; Baillie was rightly thanked in the Chancellor’s speech.

But progress is always incremental. While the policy was delayed until 2025, there was another irony in play. The commitment by Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt was aimed at encouraging work, since the 30 free hour entitlement is available only to households where both parents work.

But on the day of the announcement, the teachers’ strikes meant that for those with children in reception or higher, it was another day – after so many during the pandemic – where work needed to be set aside by at least one parent in order to create a day for a child – or children – not in school.

And so what do working parents feel about the strikes? It’s possible to imagine a world where there is widespread moaning about the fact that teachers have secure jobs, and that if they have elected to enter the profession then they ought to be there for the children.

Most people, including the teachers on strike, know that striking is undesirable, even wrong. For many teachers it’s the lesser evil; the greater evil being not to speak up about an intolerable lack of funding in the system. But, in general, when parents give vent to resentment it isn’t aimed at teachers so much as at the situation itself: pandemic parents might rightly feel that they have just had too many bad breaks these past few years.

But more often than not the mood on the front line is overwhelmingly pro-teacher. Most parents learned when homeschooling during the pandemic that they are useless teachers. It follows from here that teaching, far from being something that anyone can do – as the tone of the public discourse leads you to expect – is, in fact, a highly specialised profession. When you get magnificent teachers – as my children luckily do – everything about your family life is better. These are people whose excellence is told in patience, intellect, decency, and commitment.

That’s why the parents I speak to worry about the effect on their children’s education of their teachers being in a state of anxiety over wages. At our children’s school in South East London we adore our teachers, and though we sometimes do experience stress because of the strikes, we are also aware of what it’s like when bills go up but wages remain stagnant: there is a helplessness to that situation when you work in the public sector which, in theory at least, you don’t have if you work in the private sector where there is meant to be more elasticity on salary.

What also doesn’t get reported is that for the teachers strikes were never only about salary – very far from it. In fact, it was to do with disquiet about how the government for much of 2023 expected their own salary rise to be met. The government’s initial position was for those increases to be largely met out of schools budgets, and it was their ceding this point which led to a settlement which might have been there much earlier in the year – at far less cost to education, and less strain to parents and teachers.

Schools budgets and children’s well-being are essentially synonymous and there’s not a teacher I’ve spoken to who would ever have wanted more money at the expense, say, of after-school club provision. Such provision is the beginning of a child’s encounter with the riches of civilisation: art, music, sport, theatre, dance. No teacher, believing as they do in the development of children, wants extra money to come to their bank accounts at so high a cost to the pupils they care about.

But of course, the misery of the situation extended beyond the plight of teachers and children. It was also about parents who are on zero hours contracts and so really couldn’t manage a strike day in the same way which many workers, typically those in the middle classes, with understanding bosses could. It’s also about the whole ecosystem of the school which, underfunded as it sometimes is, is still the heart of the life of the community.

As always when hardship comes along, there are heartening stories. Some parents managed friendship-deepening play dates in central London – but again they were the lucky ones who have flexible jobs, understanding employers, and the funds to do so.

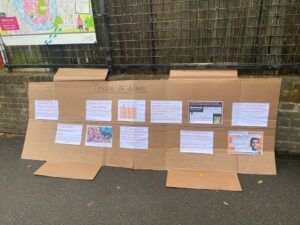

Near where we live, East Dulwich Picturehouse screened cartoons throughout the strike days on 15th and 16th March at affordable prices. Many parents also became engaged in thinking of creative ways to help their community; whether it be through playdates, fund-raising activities, or just simple words of support to teachers. Many joined them on the picket lines.

Of course, the private schools remained open throughout this year, and this led to an acute sense of a two-tier system where children from backgrounds who can’t afford it are being left behind unable to learn. Meanwhile, fee-paying schools can be seen continuing as usual: the lines are drawn vividly on strike day between the haves and the have nots. One sometimes wonders if the future is already being won and lost on such days, even if you have very young children, as I do.

Of course, while there’s life there’s hope, and a strike day can be as good as a school day if you can take your child to a museum, or some other activity.

Even so, all these problems seemed so intractable that they are crying out for the clarity of photography. In the photographs which accompany this essay we hope to cut through the complexity to arrive at images which show the simple truth of our times. We see the empty classrooms where light from a beautiful spring day falls not on the faces of children but on empty furniture; we see the thoroughfares of a local school, usually frantic with parents in the rush for drop-off now vacant, the trees almost seeming to ruminate on an unexpected quiet; we see a lone parent doing nursery drop-off, as testament to the way in which schools and nurseries sometimes feel like separate ecosystems in our society.

It is an image of a struggling country. Gillian Keegan – a likeable and impressive Education Secretary – deserves credit for the eventual settlement, but it should have come sooner, and some of the fault lines which the strikes showed remain with us today. And with that it isn’t Shakespeare who springs to mind, but Yeats with his line that; “Things fall apart/the centre cannot hold.” This is a country which hasn’t fallen apart, but there is the sense that without smart moves from the Sunak government, it soon could.