Christopher Jackson

In person, Ian Botham is utterly solid, calling to mind a rugby prop forward more than England’s greatest cricketing all-rounder. Botham is a famous wine enthusiast, and hunched over his lunch as if he could easily eat one’s own meal as well, it would be a lie to say one can’t see that he’s enjoyed himself from time to time.

Botham is one of those very few sportsman whose achievements carry across the generations. Sport is really to do with the dramatic maximisation of the present moment: we are rarely quite so conscious of life as when we watch closely to see whether a ball has nicked a bat. Especially because there is so much of it, little sticks in the mind.

1981 and All That

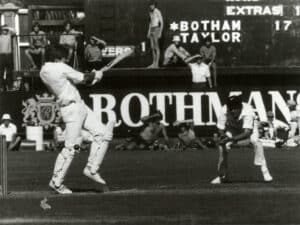

Something about Botham did: it was to do with the fearlessness with which he played the game, allied always to a certain laddish humour which is still in evidence today. Especially Botham is known for the Ashes in 1981 now forever known as Botham’s Ashes, when Botham’s swashbuckling 149 not out at Headingley began an unlikely set of events. Not until 2005 would cricket come alive in this country to anything like the same extent.

When we think back on that Test match, It should really be Bob Willis’ test, since it was Willis, who died of cancer in 2019, took 8-43 to bowl out the Australians. Willis hangs over lunch, since Botham is here to raising money for the Bob Willis Fund which raises money for better prostate cancer research.

Botham tells a wonderful anecdote about that storied day in 1981: “Australia needed a 130 to win. The Australians were 50-1. Bob comes on, and turns to Briers [Mike Brearley, the then England captain] and he said: ‘Any chance I could have a go down the slope with the wind?’ He steamed in and took 8-53.”

This led to an amusing administrative issue over the unexpected celebrations which Botham, as the world knows, enjoyed more than anyone. “We had this young lad – Ricci Roberts, a 140year-old: he was over from South Africa as a runner. I said to him: “Look we haven’t got any champagne, because obviously thought we weren’t going to win the game.” The Australians thought they would. I said to Ricci: “Go and knock on the Australians door, and be polite and just say: ‘Could the England boys have a couple of bottles of champagne, please?” He did exactly that, but added on the end: ‘Because you won’t be needing them’.”

The Australians may not have reacted well. Botham continues: “Ricci came through the door horizontal. He had one bottle in each hand and he didn’t spill a drop. Ricky Ricci went on to be Ernie Els’ caddie in all Ernie Els’ major wins. That was down to what we taught him – and how Bob taught him to pour a pint.”

The Two Geoffreys

At Lord’s, alongside the extraordinarily likeable Geoff Miller, Botham gave a jovial tour through his career, joking that Geoff Miller was ‘the livelier of the two Geoffreys I played with’ referring to his long-running grudge against Geoffrey Boycott, who Botham famously ran out in Christchurch in 1978. On that famous occasion, Boycott was batting at his usual glacial pace when the situation required runs. Botham picks up the story: “I was asked by Bob, who was then the vice-captain, to run him out and I said: “I’m playing my fourth game and he’s playing his 94th.” Bob replied: “If you don’t do it, you won’t play your fifth.”

It is impossible to not feel nostalgic about the fun of those times. Botham has come along way. In fact, when Botham recalls his upbringing, as is usually the case with the extraordinarily successful, his story comes into focus in all its glory and improbability: “My father was in the services in the Navy and was serving in Northern Ireland on active duty. When his wife Marie, my Mum, was due to give birth, they sent us over to Heswall in Cheshire.”

Crunch Time

The family then moved down to Yeovil and Botham, having shown exceptional sporting prowess, had a difficult decision to make by the age of 15. “I had to make a choice between soccer and cricket. Crystal Palace offered me an apprenticeship. I had just signed at 14 with Somerset – I registered with them and when it came to the decision, I sat down with my dad. He said: “You are by far a better cricketer”. I listened to him – for once.”

Botham then transferred to Lords for a year and half, before being called back to Somerset at 18. It didn’t work out too badly, did it? Botham smiles: “Not too bad.”

Botham recalls his first Test match. “The way they did it in those days – well, let’s just say it wouldn’t happen nowadays. You’re driving down a motorway. At three minutes to 12 you turn into a layby and switch the radio on and wait for the 12 O’Clock News. And the England team to play Australia is…And I thought: ‘Yes, I’m in’.”

That sent Botham up to Trent Bridge, where another lovely anecdote occurs. “We lined up at the start of the game and it was the Queen’s Jubilee. The Queen went down the England line, and wished me luck on my debut. Then she went over to the Australia line, and came to DK Lillee [the great Australian fast-bowler].

Dennis pulled out of his back-pocket an autograph book. “Ma’m, would you sign this?” She said: “I can’t do that now.” But clearly the Queen had remembered the encounter. Botham continues: “When Lillee got home from the tour six or seven weeks later, through the letterbox there came this envelope with the Royal seal and there was a picture of the Queen. It now sits on his mantelpiece.”

Merv the Great

It’s a lovely story – and the more time you spend in Botham’s spell, the more the stories keep coming. Merv Hughes also gets the Botham treatment. “In 1977-78 we toured Australia, one of my first tours. We were sponsored by a company called JVC Electronics. They decided in their infinite wisdom that on the rest day morning at about 10 o’clock – when most of us had only been in bed 10 minutes – we’d go to a shopping mall in north Melbourne to mingle. None of us were particularly excited about that prospect.”

So what did Botham do? “I hid behind this tower. This young lad came up in a tracksuit and said: “Good day, Mr Botham. Mate, I want to be a fast bowler have you got any advice for me?” I wasn’t feeling great so I said: “Mate, don’t bother – go and play golf and tennis.”

Fast forward to 1986: the first test at Brisbane. Botham recalls: “Merv Hughes makes his Ashes debut in that game. In Brisbane, you could see this little black line, that in about 30 minutes became a thunderstorm – hailstones the size of golf balls. Hughes bounces it in, then the gigantic hailstones. Merv wasn’t happy as I’d hit him for 22. We weren’t going to play anymore, the ground was covered with these golf balls.

One of the lads brought me a beer. Merv comes out and I say: “Congratulations on your first Ashes.” He said: “You know we’ve met before.” I said: “No. Where?” “At the shopping centre in Melbourne.” I was that kid who came running up to you, and you told me not to be a fast-bowler but to play tennis and golf.” He said: “What do you reckon now?” I said: “I was bloody right.”

Beneath the swagger of the public persona, there is his immense generosity as a philanthropist and his life as a family man. His grandson, James, is following in Botham’s footsteps as a sportsman. Botham speaks with evident pride: “He’s had a couple of years with injuries. His confidence is back – he played very well against South Africa at Twickenham. James was born in Cardiff and said: ‘I’m playing for Wales’. He’s got a task on his hand and we’ll see.”

A Decisive Difference

But it’s the philanthropy which really brings a tear to the eye. “I’m very proud of it,” says Botham. “In 1977, I was playing against the Australians and stepped on the ball and broke a couple of bones in my foot. In those days you didn’t stay with the England squad, you got sent back to your mother county. Mine was Somerset. So I get to Musgrove Park Hospital in Taunton, the club doctor’s waiting for me. To get to the physio department you had to go past the children’s ward.”

This turned out to be a fateful walk since it would change many peoples’ lives. “You can see children who are obviously ill – tubes sticking out, and their feet up. There were four lads sitting round the table playing on the board games. I said: “Are these guys visiting?” He said: “No, they’re seriously ill.” I said: “But they look fine.” He replied: “You’ve got eight weeks of intensive treatment to get it right for the tour. Those four lads in all probability will not be there when you finish your treatment. True enough at the end, all four of them had passed away.”

It made a deep impact on Botham who found he couldn’t stand by and do nothing. “What the hospital used to do was give them a party, whether for one of their birthdays or for Christmas. And they were so drugged up with painkillers. As I was leaving the hospital, I said: “Is there anything we can do to help?” He said: “Well, you’ve now seen four parties. We don’t get any funding for those.” I said: “I’ll stick my hand up and pay for the parties.”

By mid-1984, Botham wanted to do something more substantial. “I was flicking through a magazine which someone had left on the train – a colour supplement. There was an article about a certain Dr Barbara Watson, who lived on the south coast. Every summer she would get on the train and go to the most northerly part of the UK, John O’Groats and meander back. I thought: “Right, I’m going to do a sponsored walk. I’m going to do John o’Groats to Land’s End. My geography wasn’t great. 400 miles to the English border, then 600 miles to the Land’s End.”

It was a huge learning curve for Botham who had never walked like this before, but he managed to do the walk in 33 days. “You couldn’t do PayPal: you had to physically collect. By the end of the walk we got over £1million. That was used immediately to build a research centre outside Glasgow.” Then the conglomerates came behind us. “When we started the walk, there was a 20 per cent chance of survival for kids with leukaemia – a few years ago we announced it is now 94 per cent.”

It’s an astonishing story of how something so innocent as being good with a bat and ball and can lead with the right heart and mindset to genuinely consequential change. Botham’s is a reminder to us all to start with what we’re good at – but to keep an eye out for what we might do for others along the way.

Lord Botham was talking at an event at Lord’s Cricket Ground in aid of https://bobwillisfund.org/

https://www.beefysfoundation.org

Like this? See also our other cricket articles:

Cricket Nostalgia: Henry Blofeld on PG Wodehouse, Ian Fleming and the Remarkable Cricket of the Past