Why is Rafael Nadal so important? As the great tennis-player retires, it is clear he inhabits very rare company, writes Christopher Jackson

It is the humility of Rafael Nadal which is part of what makes him so magnificent. Retiring from professional tennis in mid-November 2024, he described himself as ‘just a kid who followed his dreams’.

He was that, of course. But his great rival Roger Federer came closer to the mark when he wrote in his moving statement marking Nadal’s departure from the sport: “You made Spain proud. You made the whole tennis world proud.”

In fact, Nadal – like Federer himself – comes from a very small group of sportspeople who make the whole world proud. They are a credit to their species. Part of living in an era whose defining obsession is sport is to find a dramatic increase in the type which we might call the elite of the elite of the elite.

The group I am describing is not made up of No.1’s – though all of the people I would put forward for this category have been at one time or another the best in the world at what they do. But being no. 1 in the world doesn’t get automatically get you entry to this club. Being the best in the world here is a mere starting point to being perhaps one day somewhere near this conversation.

Anyhow, you need to be World No. 1 for a long time to qualify. You have to be world no.1 over and over and over – but even that doesn’t get you there. Rory McIlroy has been the no.1 golfer time and again, but he isn’t in this category: he isn’t actually particularly close. The English swing bowler James Anderson is closer, but not quite there either.

To be in the elite of the elite of the elite you need to do things nobody else can do – in fact, you need to perform at a level to which nobody else has ever performed. And you need to do it in a certain way. We can call this genius, or magic.

In the first place, it has partly to do with ease of doing – or apparent ease. When we watch Simone Biles performing her floor routine we can see that she is doing much more than the relatively prosaic thing of winning her gold medal. She is reinventing that sport: she is qualitatively different. The same used to be true of Federer when he would waltz through a Grand Slam without dropping a set. It wasn’t just the ease with which he did this – it was the beauty with which he did it.

Usually the elite of the elite of the elite express themselves in memorable moments – moments where time itself might seem to slow down, to expand, or to become elastic in some way. Furthermore, these moments will usually be tied to some form of necessity: they therefore represent necessity surmounted, or responded to with unusual skill and awareness.

These are the moments which send a shiver. One thinks of Michael Phelps in the Beijing Olympics in the 100m breaststroke. Going for his seventh gold medal – to tie the Michael Spitz record which he subsequently beat – he was looking tired coming down the stretch against Milorad Cavic.

Then something happened. Nearing the finish, Phelps summoned some last ditch strength, and rose out of the water with a sudden show of speed, to tap 0.01 seconds ahead of his rival. He rendered himself above an impossible moment.

Tiger Woods was able to do the same. At the 2005 US Masters, Woods needed a birdie on the famous 16th hole. His drive went left down a precipitous slope. Viewers at home tend not to know how difficult the greens at Augusta National are: it’s like putting on glass.

Woods, as every golf fan knows, lofted the ball up and it ran down the slope. It teetered on the edge of the hole then toppled in. Woods went on to win the tournament. He needed to do something nobody had ever done before and he did.

The presence of someone who is in the elite of the elite of the elite doesn’t always need to come in moments when their backs are to the wall. It can also show itself with a certain ease of doing which can lend itself to a sort of inverse drama: it is the drama of things not being close at all.

In this category one thinks of Usain Bolt at the 2008 Beijing Olympics already celebrating about 80 metres in as he broke the world record by a vast margin. He looked almost as if he was flying. Nobody else has ever looked like that. In Bolt’s case it was tied together with a sense of theatre which in retrospect had to do with an extra awareness about the nature of the occasion: the nature of the occasion being that he was very likely to win and so could afford to lark about a bit.

Michael Jordan is another example. When we watch reels of him hanging in the air before dunking a ball, it really can seem as though he has a different relationship to the essential physical structures of life to everybody around him.

In team sports sometimes we find a certain heightened sense of strategy and inventiveness – the ability to conduct surprising situations with a certain innate virtuosity. In this category we find the great footballer Pele. I have always been fond of the last pass that leads to Carlos Alberto’s goal against Italy in the 1970s World Cup Final.

Pele looks like he’s playing against children. He collects the ball with his left foot, cradles it briefly, and then with a kind of infinite laziness sends it off to Carlos Alberto, who rifles into the net.

Some of my favourite Pele moments have almost a kind of silliness to them. The attempt to score from behind the halfway line against Czechoslovakia in the group stages of the 1970 World Cup. The ball misses, but its sheer audacity opens up onto a whole realm of possibilities about how we might play football.

Similarly, in the same tournament against Uruguay, Pele is running towards the box and the keeper coming towards him, both towards a cross coming from the left wing. Instead of trying to poke it past the keeper, Pele lets the ball go and circles back on himself while the goalkeeper flounders. That he then misses the goal doesn’t matter: he’s shown that there are another set of possibilities for the people to come after him to explore.

Sometimes the elite of the elite of the elite can create moments which enter national folklore: inherently patriots, they can have a heightened sense of what their country requires of them. In 2008 Sachin Tendulkar, batting against England in the wake of the appalling Mumbai attacks, needed to produce a century to lift his country’s spirits, and he did. There can be something solicitous about the elite of the elite of the elite: they do what we need to them to do on our behalf.

Clive James used to tell a story of Joe DiMaggio towards the end of his career. One of the greats of his sport, he was asked why he was warming up so hard when the game didn’t matter all that much in the context of a hugely successful career. “Because there’s a kind out there who hasn’t seen me play before,” came the reply.

When this top flight of sportspeople are obstinate, their obstinacy can take on infinite proportions. Shane Warne, another member of the elite of the elite of the elite, was once asked who was the best batsman he’d ever bowled against. He replied: “Tendulkar first, then daylight, then Lara.” Asked why, he recalled how during one particular tour Tendulkar had found himself getting out to the cover drive. Unprepared to accept this reality, he simply cut the shot out of his repertoire all day long. Warne was shocked and delighted at the sheer determination of the man.

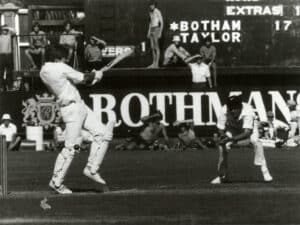

Warne shows another example of the way this rarefied group can respond to circumstances. In Warne’s case, everything he did was characterised by a certain adventurous humour. During the 2006-7 Ashes, Warne was provoked by Ian Bell’s sledging to produce his highest test score. Bell, who Warne had been calling the Shermanator throughout the series, chose to answer back.

Warne pointed his bat at Bell who was in the slips and said: “You mate, are making me concentrate.” Warne went on to score 71 from 65 balls. The implication is that he was so good he could stand in the great arenas of his sport, and not need to concentrate. But if you ever provoked him to do so, he could be as much a batsman as a bowler.

Nadal reached these heights not because it was easy for him, but because he managed to balance extraordinary effort with profound humility. It was this which made him seem, as commentators frequently said, of another planet.

That perhaps is what really unites these great sportspeople: they feel separate from us – they seem to resemble gifted visitors. One is sometimes left with the impression that the gulf between us and them is too great for it so be possible to learn anything from them.

And yet at other times, it seems as though they have everything to teach. What makes it all a little easier to swallow is that time and again they teach the same sorts of things: hard work, humility, endeavour, a mysterious depth of commitment and even humour. We will need all those things in our own lives: that’s we won’t go far wrong if we make the Nadals and the Federers of this world our mentors.