With the sad news of the great artist’s death, we look back at our review of Frank Auerbach’s Charcoal Heads, Iris Spark

Sometimes I think of those who achieved a lot young: John Keats, assured of immortality by writing a handful of odes, but dead at 26. Then of course we have Schubert, learning counterpoint on his death bed, but surely certain that the music would survive. It is a source of continual amazement that Georges Seurat managed to paint such perfect and revolutionary canvases by the age of 31. In each of these cases we have a navigable oeuvre: Keats’ output, though considerable for his age, can be encountered in a few days. You can make a provisional assessment of Seurat’s pictures online in ten minutes.

But then there are those at the other end of the longevity spectrum – the fantastically productive and long-lived. In music, Elliott Carter wrote music every morning until his death at 103 and I suspect I’m not the only person who doesn’t know where to begin. In literature, the Greek playwrights were all fantastically long-lived. In retrospect perhaps it’s a blessing that we have only seven plays by Sophocles, who lived to be 90; he wrote 120. Art, as David Hockney pointed out, seems to be good for life expectancy. Picasso, Monet, Renoir – not to mention Hockney himself – are all long-livers.

Which brings us to Frank Auerbach, already 93 and counting. It is fascinating, if you go to the Courtauld Institute, to be confronted with a little corner of his oeuvre across two rooms in that lovely gallery on the top floor.

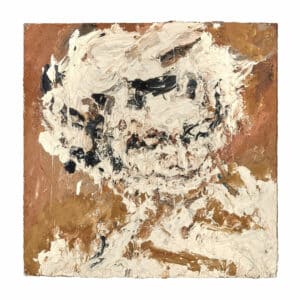

These are the magnificent charcoal drawings which Auerbach made just after the Second World War on his way to becoming, with Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, one of the three most important artists of the so-called School of London. The Courtauld introduces the drawings with the following claim: “Auerbach’s charcoal heads – heavily worked and scarred but enduring and vital – connect us to the tenor of the post-war years.” Just when you think that the gallery may even be underselling Auerbach’s achievements, the next part of the placard expands on that thought: “Made over long periods of time, the drawings offer us experiences of what it feels like to engage deeply with another person.”

This rings true. For a long-lived artist, Auerbach is in fact relatively easy to place. He is not, like Picasso or Hockney, continually moving onto the next thing. This is, in fact, to put the matter rather mildly. He still works today out of the same Camden Town studio that he worked in in the days which this exhibition charts over half a century ago.

Auerbach seems to be a creature of stasis and even of obsession. Just as Degas had his ballet-dancers and his women at their toilette, so Auerbach has his heads, and a bit of Mornington Crescent. We might say that he is a vertical and not a horizontal artist. To gauge his obsessions we must consider all that he doesn’t paint: hills, trees, fruit, any buildings not on Mornington Crescent, and any people apart from his small circle of friends who interest him. Even in respect of the last category, he tends to paint their heads and not the rest of their bodies.

Auerbach then seeks to understand the world by excluding all that doesn’t interest him, but this is not a problem. What I think he is proclaiming is his love for the things that he does paint. It was John Donne who spoke in his great love poem The Good Morrow of ‘one little room an everywhere’. Something similar is happening in Auerbach: he proclaims in paint that all the universe might be found in a face, or in a section of street.

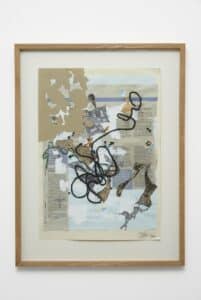

He is helped enormously in this endeavour by the fact that he is so obviously correct, as these marvellous pictures prove time again. An Auerbach head is a document of the artist’s engagement with the sitter over a long period of time. Each day the sitting would accrue its truth, and often then be scrubbed away at by the artist, sometimes so violently as to tear the paper. This creates a startling effect where creation and destruction are in some way married in one image, as is the case with one of his few living rivals Gerhard Richter.

The curators explain that these pictures are of historical interest in terms of charting how people looked and what they felt just after the war. This is true. At this safe distance from World War Two, which itself contained not only millions of individual tragedies, but a collective horror at what humankind was now capable of, we might look with a certain historical interest at these people. Of course, there is a limit in our ability to do so since we are still shaped to some extent by it.

But really this interpretation is limited because it doesn’t take into account the sheer extent of attention which Auerbach gives to his sitters, over 80, 90 or 100 sittings. To engage with a subject at such depth might be to go beyond the historical moment into deeper strata of life which have little to do with the latest circumstances, even those so gigantic as World War II. The effect is almost of creatures swimming up from their depths, eerily exposed.

The technique here backs up this interpretation. We have, accumulated across so many sittings, an extraordinarily stable architecture when it comes to the features of a face. The lines of the skull – jaw, and eye-sockets, and the shape of the head – are always laid down with a profound confidence. This underlayer allows Auerbach extraordinary freedom in other parts of the drawing, which conveys movement and changes of mood. He shows that the flux of life skims along a certain set of structures.

Take, for instance, his self-portrait. Nobody can be in any doubt about the shape of the face; but once that is made known to the viewer, Auerbach allows himself a freedom of interpretation which we can wonder at: a rush of charcoal at the forehead perhaps conveying the movement of thought.

Certain subjects recur and we feel that this was because he loved them. However, all these images are maimed and torn, and remade and it is hard not to feel that this mimics the frustration we feel when we really try to grapple with another person: however much we love them, they are not us, and these large drawings seem to reflect that. Iris Murdoch wrote that in love we get to the end of people; but Auerbach, you feel, only comes to the end of each drawing reluctantly, his feelings unresolved.

Irresolution though is an excellent basis for a long career; it keeps you at it. I think that Auerbach’s obsessive body of work needs to be distinguished from Degas’ ballet dancers, or from Stubbs’ lifelong need to paint horses. Those obsessions occurred in the open air. There is a feeling of necessary sequestration about Auberbach’s art, a self-sheltering from global currents. This may even amount to a sort of refusal of the outside world.

And yet this turning away never works: in the end we cannot avoid ourselves. Auerbach knows this – it is the very essence of vertical art to mine downwards, and insodoing, to find a space which other things not of that time and place can enter.

It all amounts to a perfect little exhibition. Of course, it is a very serious one, and as you walk out into the rooms with all the impressionists in, blazing with so much colour, you might reflect that this sort of picture-making is for a certain mood only. But there’s greatness here – the greatness of a thing done well out of passionate belief in art’s potential, hard work, monomania, and love.

Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads closes on 27th May, but an online tour will be available thereafter on the Courtauld Institute website.