Jon Sopel

I am sometimes asked about why I left the BBC. I remember the corporation went through this spasm of asking themselves how to attract the young. If you watch the news, by and large you’re over 60. The same is true of the Today programme.

The editor of the 6 O’Clock News was thinking about how we get more young people. Do we need younger presenters? Or do we need old people like me talking about young people’s issues? This was at a time when LPs were making a comeback. We sent a young reporter down to Oxford Street, and said to a teenager, holding up an LP: “Hello, I’m from the Six O’Clock News. Do you know what this is?” The teenager replied: “Yes, it’s an LP. What’s the Six O’Clock News?”

Thinking back to January 2021, I can’t forget the day after the inauguration when Joe Biden was finally President. Washington DC that day was less the elegant neoclassical city that most people remember from the Capitol through to the Supreme Court and the great museums that go to down the Mall. It was a garrison town, the place was absolutely sealed off. There were rolls and rolls of barbed wire because of what had happened on January 6th. I will never forget the shock of that.

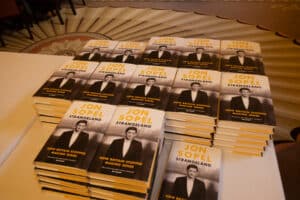

January 6th is also inscribed on my mind. I’ve been in situations where I’ve faced greater personal danger, when you’re in a warzone and you’ve got a flat-jacket one, and there’s incoming fire. But I’ve never seen a day more shocking than January 6th when the peaceful transfer of power hadn’t happened. I went on the 10 o’clock news and the mob still had control of Congress and Joe Biden’s victory still hadn’t been certified. That’s the starting point for my new book Strangeland: I wonder how safe our democracies are. My experiences in America made me realise that we cannot be complacent in the UK.

Another thing happened the day after January 6th. The Capitol had been sealed off by razor wire and I went as close as I could, and went live on the 6 O’Clock News. There were lots of Trump supporters around and they heckled me throughout so that the anchor Sophie Raworth had to apologise.

It soon morphed into a chant: “You lost, go home! You lost, go home!” I was trying to figure out what that meant. At the end of my live broadcast I said to this guy: “What on earth does this mean?” He poked me in the chest and said: “1776.” I thought: ‘Do I explain that my family was in a Polish shtetl at that stage?”

Peter Hennessey, the great chronicler of government in the UK, talks of the good chap theory of government – you rely on people to do the right thing otherwise the system falls apart. I came back to the UK at the beginning of 2022 after eight years in America. The first election I voted in was 1979. For the next three years I knew three prime ministers: Margaret Thatcher, John Major and Tony Blair. In 2023 we had three in one year – that’s a reminder of the volatility of the times we live in. In many ways in 2016 – with Brexit and with Trump – the world jumped into the unknown.

It’s always seemed to me that the Labour Party finds power a really inconvenient thing to happen. They much prefer it when they’re forming Shadow Cabinets and discussing the National Executive. Then you’d get pesky people like Tony Blair who come along and remind them it is about power. The Conservative Party was always the ruthless machine of government: there is an element in which the Conservative Party is in danger of going down the Labour Party route. It was the Conservative Party membership, for instance, who gave us Liz Truss, the patron saint of our podcast The News Agents. We launched in the week she became Prime Minister – and my God, she was good for business.

What would Britain look like if there were 10 years of Starmer? He’s done the doom and gloom, and how everything is the Conservatives’ fault. That’s fine – but so far, he’s not set out what the future is going to look like under him. Is it Rachel Reeves’ vision of the growth economy? Or is it Rayner’s vision of increasing workers’ rights. I think Starmer is an incrementalist and simply doesn’t know. If he has any sense at all he will look at the centre of political gravity in the electorate and go for growth because that’s what the country needs.

Hospice UK do the most amazing work. The book I’ve written Strangeland deals with the challenges facing Britain at the moment. Hospice UK do the most amazing work. Strangeland deals with some of the huge challenges facing the . Hospice care is one area where something urgent needs to be done.

Jon Sopel was talking at a Finito event given in aid of Hospice UK. To donate, go to this link: https://www.hospiceuk.org/support-us/donate