Christopher Jackson

There used to be a dead tree in Ruskin Park in South-East London, which always struck me as somehow sculptural. The other day I saw that it had fallen. I had grown so fond of this particular tree, it’s optimistic reach towards the skies, that I was bereft when I saw it had collapsed.

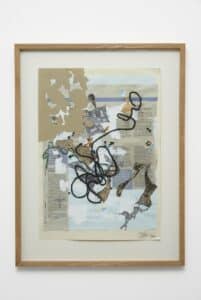

But this probably minor development in the history of my local parklands makes me all the more delighted that this same tree is still standing in the work of a remarkable artist Nadeem Chughtai. Chughtai’s recent exhibition A Liminal State has people talking in Peckham, which as everybody knows is also the artistic centre of the universe. Chughtai used the tree as a basis for his picture There’s This Place On The Edge of Town (2020).

One of the most basic requirements of an artist is power: Chughtai’s images always have an immediacy which nevertheless lets you know that your first impression is only the first part of your journey with that work of art. In this picture we see how we have become mechanised in ourselves, and how this can only lead to stunted growth. But the beauty of the tree, which looks like it almost wants to be an upwards staircase, suggests potential.

It’s a brilliant conception, like all Chughtai’s pictures. So was it always art for him, or did he toy with other careers? “It really was art all the way for me,” Chughtai tells me. “Ever since I was very young I’d draw. Encouraged by my mum and influenced by a beautiful framed pencil drawing my dad made of my mum in the 1960’s. However, I did loads of jobs before going full time with an art publishing contract which set me on my way. Before that I always kept myself in the minimum wage positions for fear of committing myself further down other career paths.”

Chughtai has had some major successes, with some celebrity clients including Roger Federer who chanced upon his work in Wimbledon village one year. Chughtai is particularly well-known for Nowhere Man, his character which he gave up at the start of the pandemic. These pictures, taken together, amount to a vast dystopian opus which tell the viewer unequivocally what we all sense: we are not headed in the right direction as a species.

We never see Nowhere Man’s face. Sometimes there’s more than one of him. It is also possible to say that Nowhere Man is always in a negative setting, beset by the circumstances of modern life: alarming architecture, the trippiness of drug culture, the terrifying ramifications of contemporary uniformity.

I also note that they’re always dramatic force in these pictures, and I related this to the career Chughtai had on film sets, with his work including the Bourne series and Love Actually. Did that experience impact the way he paints now? “Yes, I always mention my scenic art days. I call it my apprenticeship. It was absolutely magical to be working on those film sets at Pinewood and Shepperton Studios,” Chughtai recalls. “I originally went there to try and make films after losing my way with drawing and painting after college, but as soon as I saw the huge painted scenery backdrops surrounding the sets I was sucked back in.

I had hands on experience of painting pictures on giant canvases, off scissor lifts using strings, hooks and chalk to draw our lines. I learnt about so many aspects of painting as well as the cameras eye. The big one was perspective. Learning about that was enlightening for me.”

I ask Chughtai if he has had any artistic mentors, and his answer also dates to this time: “Well, I always mention Steve Mitchell, the scenic artist who I assisted over a five year period from 1999- 2004. He’s still doing it at 70 and we’re still in touch. He’s one of the world’s top scenics. I can’t tell you what I learnt over those scenic years and how it got me back into the art of painting.”

I can tell how passionate Chughtai is about his calling, but the melancholy of these pictures is always there. It seems to cry out for some kind of remedy. Is Chughtai pessimistic about the human race and its future? “I believe we are not only on the path to a dystopian future but within it now. Just look at all the horrific and unnecessary human suffering going on all over the world and right down to our own neighbourhoods. However, I remain an eternal optimist and have every faith that the human race will unite to overcome this and bring about the necessary change required.”

The new pictures, with their liminal greens, seem to be the start of some new potential. Here we see Green Park as it might be seen in a dream, or in the hypnagogic state between sleep and waking. The journey to the centre of town to make these pictures is perhaps indicative of an interior shift in Chughtai. The new pictures also mark a big change away from character towards some other kind of painting which feels like it is yearning for mysticism – maybe even a metanoia away from despair.

Was it hard to give up Nowhere Man? Might he ever experiment with another character? “It was very hard to shed the Nowhere Man. I doubt there would ever be another character. For me it represented humanity. If I ever need a central character again I’m pretty sure I’d call him up.”

Humanity then is for Chughtai somehow passive and faceless – asleep perhaps. This makes the notion of an exploration of the liminal all the more important; it is to do with exploring what Seamus Heaney called ‘the limen world’, that curious borderland of the unconscious. I have a sense that these recent works are a necessary transition period and that it may in time lead to some sort of reconciliation between Chughtai and the damage of the world – a more optimistic vision perhaps.

How did these new paintings come about? “The works exhibited recently at the Liminal State exhibition are exactly that; Liminal, as in kind of between or on the threshold. For me personally, up until just before lockdown in 2020 I was creating paintings with a central anonymous figure – the Nowhere Man. 16 years through the eyes of this character, so, shedding that to allow the next body of work to arrive has taken these last four years, and counting… The title, A Liminal State can also have numerous interpretations and could additionally refer to many other aspects; mentally,, physically, technically, artistically, societally… liminal.”

These then are between states, and that means flux – in Chughtai’s art certainly, and therefore, since artists are their art, in his life. I ask Chughtai about his method of composition. Is it evolving? “It’s evolving and continuing its journey. I’ve changed the approach, technique, materials used and so much more since 2020. In fact, almost everything – but still the work has naturally evolved through different states to where it is now.

It’s a continual fluid journey. I have also been developing an artistic theory and putting that into practice. It involves perspective and the way the eyes see and the brain interprets an image. It’s great testing a science based theory on my artistic practice… and it actually works. My most recent painting entitled, Turn Left. (2024) shows the theory in practice in its most developed stage to date, and I was blown away by the positive reaction it got when exhibited for the first time at the show.

This again, seems to me like a dream where the dreamer is sometimes given clear but mysterious indications of what to do – strange snatches of disembodied advice. To look at these pictures after immersing oneself in the Nowhere Man corpus is to see a kind of hope peeping through, because the world seems to be acquiring a kind of charge, groping towards some form of meaning. My sense is that this makes the next few years of decisive importance for Chughtai’s art. If we follow that sign, where does it lead?

This new work has also sent Chughtai on a rewarding course of study. “Over the last four years I have really delved deep into studying and expanding my artistic learning. Visiting the London galleries on a weekly basis and getting to understand the philosophies of some of the great painters, while also educating myself about the amazing artists from around the world and their histories.”

So who are his heroes? “I have to mention Van Gogh, I just love. His pencil drawings, they make me wanna scream. I would say that more recently I have been appreciating 20th century Western heavyweights such as Bacon, Klee, and Rothko who’s section 3 of the Seagram murals brought me to tears on more than one occasion. It was during a particularly emotional time for me personally whilst simultaneously looking to move my work along an different path. That painting allowed me to see within it what I wanted to do with my own work.”

Chughtai has been going strong for a long time. So what are his tips for young artists about the business side? “Well, yes, it is a business – if you do it full time for your living. So if you don’t have the luxury of financial security, you will need to sell your work.

This predicament will most likely influence the type of work you produce and therefore could involve compromise. That’s the tightrope. It can work in your favour but can also be a hindrance if not deterrent, which is a real shame because then we miss out on hearing and experiencing the voices from within those walks of life. So, believe in what you’re doing, put the time in and keep on making your art.”

And would Chughtai recommend the art fair route? “I love going to art fairs. It’s where it all started for me. Like our society, the art world is very hierarchical, but whether you’re at the bottom rung or at the very top, when all is said and done they’re markets with their stalls out. It’s great because people can stand in front of the work in the flesh, which is how I feel art works are best experienced… and there is so much under one roof. Art fairs are a great way to spend an afternoon… if you can afford the entrance fee, of course.”

That’s often the problem for young artists at all. Has the conversation around NFTs affected him at all? “I did look into NFT’s a little some years ago but it seems to have gone quiet on that front so am unaware of where it currently stands. The whole digital thing is obviously a direction the art world is going down and there are many possibilities to explore. However, my focus and studies are with oil paint and a canvas because there’s so much more to come from there and that will always be ahead of any artificial intelligence.”

Chughtai is an artist of rare talent, who is doing something very valuable: he is pursuing his vision where it leads. It takes courage to do that. Every artist can learn from somebody who has chosen his path so decisively then pursued his craft with such passion.

For more information go to nadeemart.com