Notes Towards a Meaningful Career, George Achebe

Lately I have been thinking about something rather fundamental: the meaning of work. This is, after all, something which at Finito we seek to secure for our candidates: a meaningful career. But meaning, after centuries of philosophy, tends to have a somewhat slippery nature. Sometimes we glimpse it more vividly by its absence: ‘Well, that’s just meaningless,” we might confidently assert, implying as we do that there is some realm where meaning might reside. Sometimes, we are lucky enough to receive some clear sense of intuition: “I really must do that,” and it is an interesting question, though outside the scope of this article, as to why these prompts do seem to arrive in human beings.

All these matter, however, become no less straightforward when we come to consider the question of meaning as it relates to careers. This is not too surprising since work is what we spent such a large part of our lives doing – so much so that the two are hard to separate.

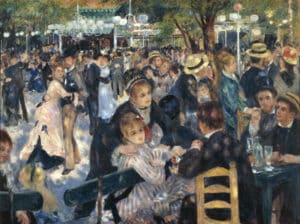

And yet it is a very common wish: I just want to do something that matters. Similarly when we say: this isn’t for me, what we’re typically pointing towards is the lack of perceived meaning in a particular role from our own perspective. Sometimes, this might be valid: we burn inside to paint a great picture but destiny has cruelly landed us with a data entry job. On the other hand, as we shall see, we must be careful to assign meaningless to a role without first having its explored its possibilities, and what it can teach us.

Nevertheless, I ask the revered psychologist Dr Paul Hokemeyer what in his clinical experience constitute the most common mistakes when it comes to forging a meaningful career. “Personally and professionally, I’ve discovered one of the biggest mistakes people make regarding career choice motivations comes from the blind pursuit of power, property and prestige,” he tells me. When I ask him for examples he becomes autobiographical.

“I found this to be the case in my own life when straight out of university, I decided to go to law school and become an attorney in America. While I actually loved the process of studying law, working as an attorney with a big American law firm was not suitable or sustainable for me in the long term. I also find this to be the case with my patients. Decisions made purely for external validation and the promise of riches tend to lead people into jobs and careers that while gratifying in the short run, are unsustainable or cause them to engage in unhealthy coping behaviours in due course.”

This rings true. Power has, as Rishi Sunak may soon discover, a funny way of evaporating in the hands of the supposed holder: it’s like trying to grip smoke. More generally, there are people one sees, sometimes at the bar at Conference season, who seek power but if it were to be granted them, wouldn’t for an instant know what to do with it in any meaningful way. In fact, when we consider past UK Prime Ministers, the ones we think of as having the most success usually had a relatively developed sense of the potential meaning of them holding that office, and the skills with which to see it through.

William Pitt the Younger understood that the public finances must always be on a proper footing for Britain’s prestige to remain intact – and he ensured that it was so, with considerable longevity in office as his reward. Churchill in his first term had a very clear mission – to defend the nation from Nazi Germany. But there was less purpose to his second administration other than perhaps to remain in office, and so we tend not to study it for the simple reason that there is less meaning to extract from it.

And what of the current administration? When I talk to the Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt about the meaning of the current government and whether he should be going for more attention-grabbing tax cuts, say council tax or stamp duy, he says, referencing his budget earlier in the year: “I chose national insurance because it is the tax cut which is most going to grow the economy. My cuts in National Insurance will mean that 200,000 more people will enter the workforce. There are 900,000 vacancies in the economy so these are the most pro-growth tax cuts you could have.”

Hunt implies that meaning within our work is simply to be found in honestly doing our work as well as possible, regardless of how one is perceived. But, of course, he can sometimes seem blithely unaware that his ability to continue to conduct the work beyond the next election is intimately bound up with precisely those external factors which he goes onto disavow: “To the argument that I could have done a tax cut which was a bit more retail, I think the electorate are alert to chancellors to try and bribe them for the election. If I’d done that I don’t think it would have worked.

The reason people vote Conservative is because they trust us to take the difficult decisions. Sometimes there isn’t a magic bullet and you have to do the hard yards. Making sure we have economic credibility is far more important than trying to pull a rabbit out of a hat.”

For someone like Hunt, the meaning in his work is to be found in carrying out his position responsibly, and I respect his desire to operate according to this sort of internal gauge of what is right. But what of the other potentially false motivation Hokemeyer points to: money. The Finito mentor Sophia Petrides agrees with Hokemeyer that this is a potentially dangerous motivation for a career: “Pursuing a career path primarily for financial gain can lead to dissatisfaction if the individual does not have a genuine interest or passion for the work.

Additionally, high-paying jobs often come with long hours, intense competition, and high levels of stress, which can negatively impact our physical and mental state.” But for Petrides, prestige and status are also potentially dangerous metrics by which to choose a path in life. “Some individuals are attracted to careers associated with high social status or prestige, such as becoming a doctor, lawyer, or CEO,” she continues. “While these professions often garner admiration and respect from others, pursuing them solely for their prestige can lead to dissatisfaction if the work itself is unfulfilling.

Over time, this lack of gratification can result in boredom and loss of motivation, which can be detrimental to one’s performance and success in the business world. Additionally, the pressure to maintain a certain status can contribute to stress and burnout, impacting both mental and physical well-being.”

Of course it is possible to make a lot of money, and then around that achievement to create permanent structures with which to be useful and kind, as many of our bursary donors at Finito have done. Furthermore, it may be that one is actually constructed to take an interest in economics or the markets. Warren Buffet is, for instance, someone who plainly has a fascination with the orchestral nature of markets – an orchestra which at his best he obviously found some inner meaning in conducting.

But it must be said that the world isn’t exactly stocked with passionate bankers. There aren’t many that I’ve met who fit the caricature of the Dickensian villain; more generally the danger is that certain high-flying types, who have placed money at the centre of their being, exhibit a certain thinness. They are what TS Eliot, a banker himself, called ‘the hollow men, the stuffed men’.

There are other mistakes which people make when it comes to finding meaningful work. Hokemeyer pinpoints another: “Another mistake is when people make career choices based on what other people, especially parents, think they should do with their lives. Typically, these parents are well meaning. They want their children to be financially secure and hold prestigious jobs. Sometimes, however, parents are more motivated by their own self-interest or narcissistic personalities. They have created a legacy business they want to see continued, or they find ego gratification from the external successes of their children.”

Sophia Petrides agrees: “Choosing a career path based on the expectations of others rather than your own interests, while this may initially provide a sense of approval, validation, and belonging, it can lead to resentment and unhappiness if the individual feels trapped in a career that doesn’t align with their true authentic values and interests.”

We all know the trope: the unhappy banker whose father was a happy banker. In such instances – especially common among the children of the successful – what appears to happen is that a person lacks confidence to feel that meaning might be personal to them, and not somehow an aspect of one’s identity as a family member. It can amount to a crisis of confidence at the level of the soul, and is greatly to be discouraged. Whole lives have been wasted this way. Philip Larkin wrote that it can take a lifetime to climb free of your wrong beginnings.

Allied to this, again according to Petrides, might be another major reason for pursuing the wrong line of work: fear of failure. “When we live our lives in fear of failure and uncertainty, it can lead to avoiding risks and challenges in our careers, limiting opportunities for growth and advancement,” she tells me. “We may stop being creative and innovative, which hinders our ability to solve problems effectively. This complacency can lead to procrastination and a feeling of being stuck in our careers. In the long-term, this can result in stress, anxiety, and burnout, which have disastrous outcomes for our physical and mental health.”

This fear of failure is almost always allied to seeking approval from a false source. Petrides argues that external validation isn’t something which we should permit to be in the equation when it comes to carving out our path in life. “Seeking external validation or approval through one’s career choices, such as wanting to impress others or prove oneself, can lead to a lack of authenticity and personal fulfilment. Relying on external validation for one’s sense of worth can make it difficult to find genuine satisfaction and purpose in the chosen career path.”

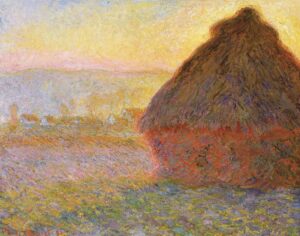

Meaning therefore needs to begin with an inward assessment. For some people, the answer as to what really constitutes meaning for oneself will be quite obvious: I simply need to paint, or be a lawyer, or play the harp. Such people are in receipt of very clear instructions, and then it becomes a question of how to do it and this will involve study, and perhaps some form of networking. None of this is to be underestimated in today’s interconnected and highly competitive world, but the task is certainly made a lot easier when an individual is certain what they want to do.

With this in mind, I ask Hokemeyer about the healthy motivations people assign to their careers and why some people are simply better at strategizing their lives than others? His reply is extremely interesting: “People who are successful at strategizing their careers are good at knowing what motivates them and what will hold their interest over the course of say 50 years.

They are also able to balance this self-awareness whilst being practical about the costs of living life and putting together an investment portfolio that can sustain them if and when they want to step back from work. It’s a melange of passion and practicality. They find something they are passionate about that they can grow into a solid commercial endeavour over time. They don’t pretend that money doesn’t matter. They get paid to do the work rather than doing the work to get paid.”

It is common to find artists particularly falling on the wrong side of this wager – they love their work but precisely because of that they somehow keep getting snookered into working for very little. It is quite common for the knowledge that one is working in an exploitative situation to chip away over time at what was once a precious inner meaning. One thinks of the musician who felt a certain fire within looking with vexation at their household bills while each Spotify play earns them around 10p in royalties. A lofty and dismissive approach to healthy finances will ultimately injure one’s sense of meaning, since the energy one needs to enact meaning will likely disappear in stress.

Yet many fail to do this, and lots of people in fact live out their entire lives with a very limited sense of what they might have been capable of. Somehow the moment of internal reckoning is put off, and put off, until it never comes. Either a mediocre occupation is arrived at, and stuck with for financial reasons. Sometimes because of a certain unaddressed internal fear, no move is seriously made at all throughout one’s existence.

A wealthy child may, for instance, live off their parents’ wealth, depleting that wealth in the process for future generations. Alternatively, someone may choose to live off the state. Unsure as to what move to make, they end up making none whatsoever. This is tragic because ultimately one has failed to be of use to society, and more broadly, to the universe.

I ask Hokemeyer why it is that we often fail to examine our core reasons for doing even quite major things, such as what career path to take? Is it that we’re in some fundamental sense asleep and need to wake up? He replies: “Human beings are herd animals. This explains why large numbers of people blindly act in the same way at the same time, following others and imitating group behaviours rather than making their own autonomous decisions. Right now there is a trend for young university students to want to major in computer science.

This, even when they are best suited to more romantic interests such as philosophy and art history. When asked why they stay in a major that gives them no joy, these young adults will say that they want to make a ‘ton of money’ and be the next Steve Jobs. Based on this, they struggle in a hyper competitive major and waste the precious opportunity to study something in which they can excel and that will bring them joy throughout their entire lives.”

This opportunity for joy is precious – and for many it is an all-too brief window. It is a reminder that we must go to considerable lengths to make our own autonomous decisions and to really ask ourselves if we are acting out of the right values, and whether we are actioning our best selves.

Tracey Jones is an advocate of mind management and she tells me that she feels the thing which we miss in our society today is ‘introspective reflection’. So what is this? “It refers to the process of looking inward, examining one’s own thoughts, feelings, and experiences in a deep, contemplative, non-judgmental manner. It involves self-examination and self-awareness, whereby individuals reflect on their values, beliefs, goals, and actions to gain insight into themselves and their lives.”

Jones’ business, called Tracy Jones Life, is wide-ranging and is all about imbuing lives with meaning: “Navigating complexities of introspective reflection is the main part of my work, where individuals can often reach a tipping point of burnout, and struggle with diverse life transitions. Whether stemming from work-related challenges, media exposure, financial changes, selling a business, or transitioning from a specific career. Providing support during these critical moments brings me a profound sense of harmony as I impart knowledge and wisdom, empowering individuals to introspect, realign, reassess, and ultimately progress equipped with a stronger toolkit.”

For Jones the benefits of this approach are many: “Understanding the mind in this way can indeed contribute to creating a stronger and more cohesive society and it can help individuals navigate conflicts more effectively. By understanding cognitive biases, emotional triggers, and communication patterns, people can approach disagreements with greater understanding and seek constructive solutions.”

However, in a complex and vast system like human civilisation today, it is impossible that everybody ends up in their so-called dream job. However, for such people, there is a sort of second chance if you read a fascinating little book by a remarkable philosopher called Dr Wilson Van Dusen.

Van Dusen has a completely different perspective. He regards human beings not so much as herd animals but as beings implicated in a broad and far-reaching pattern – and knowledge of this pattern can be activated at the level of the individual with tremendous results. He would, like most people, wish for people to be fulfilled in their work, but he points out that it is possible to maximise the meaningfulness – or as he would say the usefulness – of every station in life. He gives, for instance, the following example:

Two men own and operate a clothing store. Outwardly they do the same thing, sell men’s clothes. Look closer. One quickly sizes up the customer’s wants. The customer likes this color, that style. Let’s see — perhaps this is what he wants? Everyone is different, and the salesman enjoys finding and serving these differences. He is pleased to see the clothes he sold appearing here and there around town. The other clothing salesman pushes this or that, touts it as a bargain. The profit-making sale is his end, not the customer’s needs. He serves only himself. The first salesman serves himself and the other person. It is a mutual benefit.

So the question of whether each clothing store owner really wants to be a clothing store owner isn’t paramount for Van Dusen. Their core motivation may perhaps have a bearing on their attitude to the role but the point is that once in a role you can choose to see its value or not – and choose also whether to maximise your usefulness within that position.

Great rewards attend anybody who takes on a new role, and looks around and tries to fill it with as much creativity, empathy and other positive states as possible. Many people may read Van Dusen’s book and think: “Well, I wouldn’t mind being a clothes store owner – that’s a much better job than mine, and I don’t see how I can make the best of it.” But Van Dusen has pre-empted this response with the following example:

I am reminded of the Zen monk whose job it was to clean toilets in a monastery. The whole purpose of life in the monastery is the enlightenment that is a seeing into God and All There Is. How does this jibe with cleaning toilets? Fortunately, he used his menial task as The Way at hand for him. At first in the cleaning he was taught much of cleaning so that he probably produced some of the cleanest toilets of all time. He was also shown much of his own nature and faults.

Then he began seeing general principles in his work. Finally, after all this step-by-step preparation, he found the One, the design of all creation. God came forth and cleaned through his hands. His wisdom became apparent and he was elected abbot of the monastery. But he loved The Way that had opened for him, so he continued to clean the toilets.

This might seem far-fetched, but I can attest it is certainly worth a try. You might perhaps have been putting off paring back the lavender for the past few weeks. A plant that really ought to be providing pollen for bees, and therefore, by the success of bees, improving the diet of certain bird species and so and so forth up the food chain has, under your dubious watch, ceased to do that.

It starts to annoy you and you don’t like the feeling so you do nothing. You also might tell yourself you’re busy and don’t have the time. But what if, one day, you make the time and prune the lavender? You might be a bit surprised at how that goes. Suddenly the feeling of guilt has gone away. In a month or so, you will see bees in your garden. And Van Dusen’s point is that all jobs are crying out for use in this way.

Interestingly, Jones also took a visit to Nepal in 2023, and there watched Buddhist monks engage in ‘Monastic Debate’. She was struck by the atmosphere at the monastery: “Monks present and defend their viewpoints, challenge each other’s assertions, ask probing questions, and engage in critical analysis. The atmosphere is one of mutual respect, seeking truth, clarifying concepts, and sharpening one’s own understanding.”

Jones drew the following lesson: “The practice of debate also encourages active listening, empathy, and understanding of differing viewpoints. By engaging in respectful dialogue and considering diverse perspectives, monks cultivate compassion, tolerance, and open-mindedness, which are essential qualities for building strong relationships. Whilst I would watch these debates, it made me highly aware that we could learn so much from these ancient traditions.”

She’s certainly right about that and it all amounts for a new place to look for meaning – not in some external placement or vacancy but in a place you can actually control: yourself.

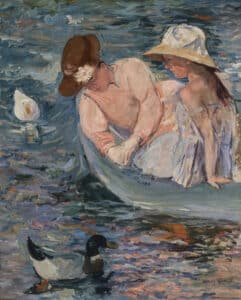

This understanding of uses, based perhaps around the sort of cultivation of compassion which Jones describes, ought to form part of any mentoring relationship. We ought to not think about we might become more successful, wealthier, and people of greater prestige: we ought to consider how we might be of use. Sophia Petrides has direct experience of this in her mentoring: “A mentoring relationship can be a powerful journey of shared exploration. Instead of solely guiding, a coach/mentor acts as a sounding board and a partner in discovery.

We embark together on a quest to understand the client’s values, passions, and aspirations. Through open conversations, we challenge each other’s perspectives and assumptions. The client might question my experiences, prompting me to re-examine my own approach. This constant exchange fosters deeper self-awareness for both of us.”

So it’s a collaborative searching for meaning. “Yes, and it goes beyond goal setting. It’s about uncovering the “why” behind those goals. The client’s journey of fulfilment becomes a mirror reflecting my own purpose as a mentor. As their understanding of their place in the world unfolds, it inspires me to re-evaluate my own guiding principles. In essence, the mentoring relationship becomes a transformative experience, enriching lives.”