by Alice Wright

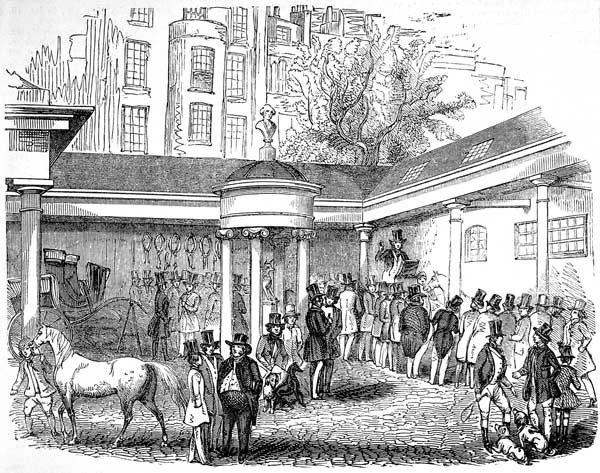

According to the British Horse Council’s Manifesto for the Horse the equestrian industry in the UK provides full-time employment to over 250,000 people and is the second largest rural employer after agriculture. It’s also a growing industry, contributing around £8 billion a year to the economy. Employment opportunities stretch far beyond riding and caring for horses. For example, the industry incorporates marketing, betting, training, retail and veterinary sectors that offer myriad opportunities to work with and for horses.

For those acquainted with the equine world this may appear self-evident, but for those with a budding interest or considering a career change the British Horse Society (BHS) helpfully breaks the various sectors down in their ‘career pathways’: Breeding & Stud; Business Management; Coaching; Tourism; Dental; Farriery; Journalism, PR & Photography; Mounted Forces; Nutritionist; Racing; Saddlery; Sales & Marketing; Trainer and Veterinary Medicine. I spoke to some of the various leaders of these sectors to find out more about the opportunities in their professions and where the industry is headed as restrictions are lifted.

A spokesperson for the British Horse Society (BHS) told me that “like with all industries affected by the pandemic, it will take time for the equine industry to get back to business as usual. With people having more spare time we saw an uptake in the number of individuals taking part in horse riding, prior to the second lockdown. This, along with people embracing the outdoors and new hobbies, is a positive sign that the industry will continue to thrive.”

Saqib Bhatti MBE MP is the Chair of the APPG for the Horse that, according to Bhatti acts as “a voice for the horse riding industry in the United Kingdom” to “give a unified voice to ensure industry concerns are heard in Parliament.” He tells me that recently their work has dealt with issues thrown up by the lockdown such as the operation of riding schools during restrictions and the classification of vets as key workers.

Indeed Bhatti’s APPG is now largely focusing on the post-Covid landscape. “We face a myriad of economic challenges and ensuring employment opportunities are available in the equestrian industry will require cooperation between industry and government.”

Indeed, aspects of the equestrian industry have been hit hard by the pandemic. Last March, the iconic Cheltenham Festival was given the government green light to go ahead despite the escalating coronavirus crisis and has retrospectively been deemed a possible superspreading event. Race meets, sales and other large income generators all over the sector were closed down for months.

Yet, Bobby Jackson, marketing executive at Tattersalls sales in Newmarket claims that bloodstock, sales and marketing has remained relatively stable. “As our side of the industry deals directly with racehorses, COVID-19 hasn’t really affected the day-to-day care of them and therefore employment levels have remained fairly steady” he says, adding that “investment levels at the Tattersalls sales have been positive during the pandemic and would infer that employment levels should remain strong in the long term too.”

Claire Williams, Executive Director of the British Equestrian Trade Association (BETA) agrees, telling me that “to be honest, the trade and retail has come out of COVID quite strong. Certainly my retailers and manufacturers are coming out probably almost with higher turnovers than they were coming in [to the pandemic]. We’ve seen a real boom and equestrian sales over the last year. BETA is recognised as the official representative body for the trade sector of the equestrian industry, representing over 800 companies in retail, wholesale, manufacturing and other service agents.

Williams is keen to emphasise just how many opportunities there are across the industry, but particularly in the trade sector. “In terms of the trade side, you’ve got everything from saddlers, to photographers, or working for a large manufacturer. You’ve got the range of nutritionists, assisting in the development of feed or to act as advisors to the customers.” Equine nutrition is constantly responding to developing research so there are academic opportunities as well as client-facing roles.

“Then you’ve got business management type positions and companies, whether that be product development, market development, marketing and sales,” Williams adds. She is also enthusiastic about the creative opportunities available, such as in product design for both horses and riders, from hat silks to winter rugs.

There are also “a lot of PR opportunities” both in-house with large companies and dedicated specialist firms such as Mirror Me PR, as well as “opportunities for more science-oriented people.” The scientific primarily relates to veterinary medicine and pharmaceuticals but Williams also mentions that there are a great deal of R&D (research and development) opportunities with companies, such as those creating supplements.

Further to this there is the management and events aspect of the trade which can be a fruitful career for the self-employed as well as those that want to work at events corporations. However, events businesses have been one of the hardest hit by lockdown and restrictions on gatherings.

BHS’ spokesperson agrees with Williams about the abundance of employment options surrounding horses, saying that working with horses will provide “a strong foundation of skills and knowledge to support any career, or career change, in the industry. It will provide you with many transferable skills such as communication, assertiveness, organisation, time-keeping, resilience and confidence” adding that, “in any career connected to horses, from journalism and graphic design to saddlery or farriery, a foundation knowledge in complete horsemanship is recognised throughout the world as a huge advantage.”

Jackson too expresses the variety of opportunity within the marketing and sales sector of the equestrian industry. “In this side of the industry, if you want a hands-on job with horses you can do it, if you want an office job you can do it, or if you want a job combining outdoors and indoors then you can do it! There are roles for all talents.”

Jackson describes how the range of jobs within sales and bloodstock itself is huge. One can work on a stud farm and bring life into the world during the foaling season, or alternatively work at an auction house like Tattersalls and help fulfil people’s dreams when they sell a horse for a life-changing amount of money. “This side of the sport will give you moments that you will never forget,” he tells me.

Yet despite the plethora of opportunities the equine industry carries an unfortunate haze of elitism over it as a profession. It is associated with royalty and high-net worth investors, and while both hold essential roles in the sector, this perception can be an initial barrier to people considering a career in the sector.

The BHS told me that “there is an inaccurate perception that equestrianism is an expensive industry to get into. While it is true that owning a horse can be expensive, you do not have to own one to be able to start your career.” Jackson agrees: “The ‘sport of kings’ brings with it positive and negative connotations.” He tells me, “some people think that you need to have family in horse-racing in order to get a job in it. Incorrect.” He also stresses that his own family background is not connected to racing.

Williams disagrees that the industry is elitist at all. “When we look at our market research, [those with] lower to medium income levels actually comprise over half of the riders in the marketplace. It may be perceived as elitist but really I don’t believe it is otherwise we wouldn’t have 1.8 million regular riders.”

Jackson also explains that “unlike most industries, travelling the world and doing multiple jobs in your early career in order to get as much experience as possible isn’t seen as a negative in horse racing. So, by working hard, getting your hands dirty and proving your talent anybody can carve a successful career in our industry and absolutely love it.” This is a point of encouragement for those considering a career change or those yet to finalise their career choice after finishing studies.

Schools, colleges and further education institutions don’t tend to include opportunities to work with horses in the usual career days advertising medicine, the law and finance. Yet there are initiatives such as Racing to School which aims to educate school children on the activities and business of running racecourses. Jackson argues that such initiatives could be broadened to the bloodstock and sales side of the industry.

He adds that at Tattersalls, children from Newmarket Academy make an annual visit to Book 1 of the October Yearling Sale and “it would be wonderful if other schools around the country were able to do similar at stud farms, for example.”

Bhatti tells me that he agrees that there are challenges to those starting out in the equestrian industry. “The APPG has found that several employers feel that students coming out of education and moving into the sector lack some practical skills or experience and it is important to encourage as much hands-on experience as possible.” One solution he suggests is “working with schools to ensure placements in riding schools and other industry-related institutions become available for students.” A large part of the APPG’s work is with educational organisations such as the BHS to make people aware of opportunities within the industry.

Williams adds that “there are a lot of opportunities for young people such as apprenticeships. For example, we’ve got gateway stages with Kickstarter at the moment. I’ve got something like 40 employers with positions they’re creating specifically for young people.”

The equine industry seems to have remained relatively stable during restrictions, and even those elements such as racing and events that have been adversely affected are set to bounce back. Despite an air or exclusivity there is such a range of job opportunities within this industry and as Williams says “to work in the equestrian trade you don’t necessarily have to be horsey. You don’t have to have an equine degree to get a job in the equestrian trade at all. What we’re looking for is people showing that they’re capable, they can write well, they can analyse and they have the business skills that we need for business.”

The BHS spokesperson offers equal encouragement: “the great news is that you can pick this up at any age or stage in your life – you are never too old to fulfil your passion for horses!” Jackson concludes with enthusiasm “what you will also find is that everyone is doing what they love – something I count myself very lucky to say – and this is a great leveller.”