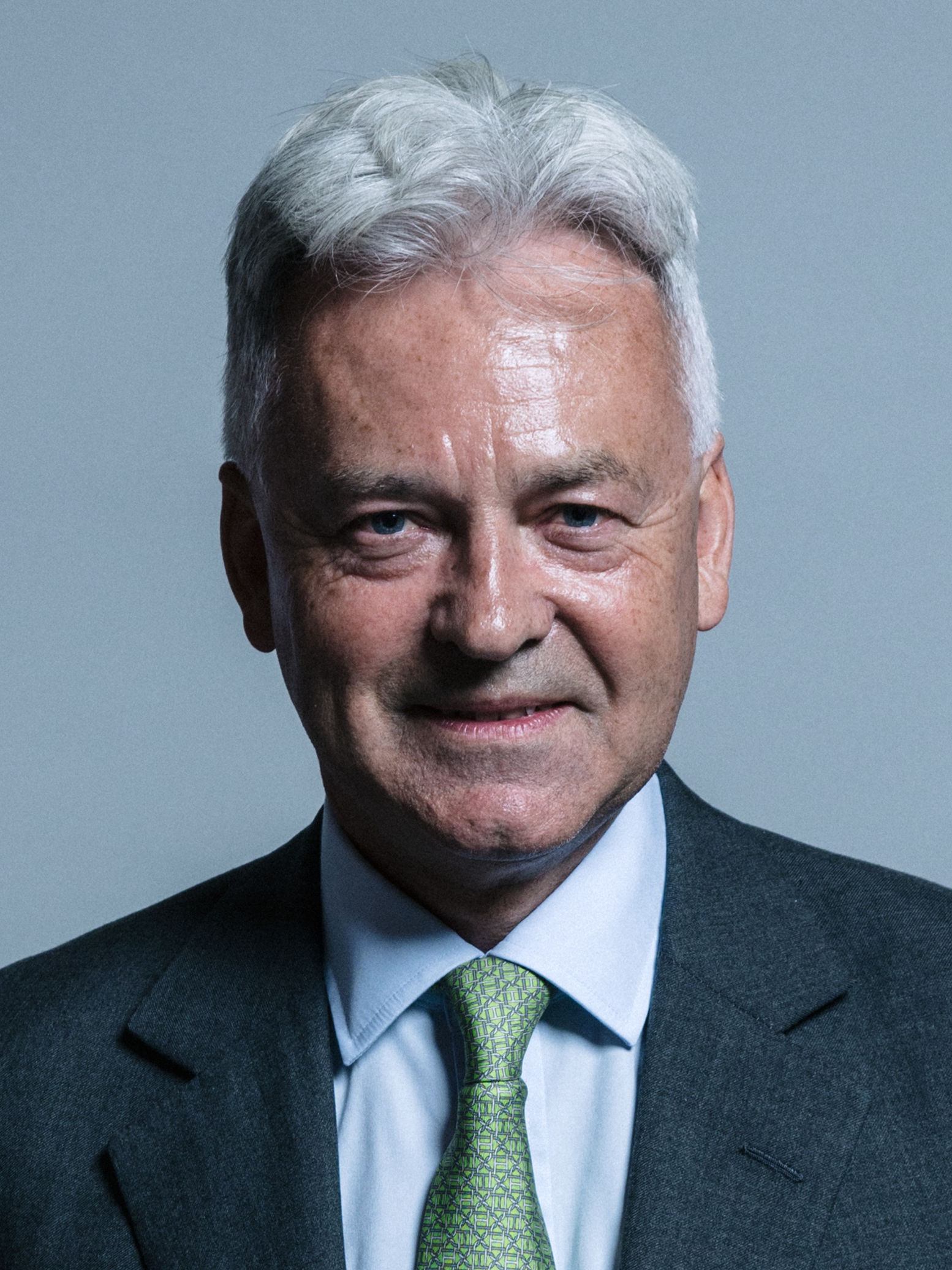

The former foreign office minister tells us about his degree and how it impacted his life in politics

I studied PPE at Oxford, and when I’m asked what my degree taught me I always think of Harold Macmillan. Macmillan was a former prime minister, who was once Chancellor of Oxford, and he said to our College, which was St. John’s, that what freshers year taught you is when someone is talking rot. That’s always been my lodestar for what a good education means: if you know when someone’s talking rubbish, you know what’s good sense and what is not.

But political ambition predated my time at Oxford – I got the bug actually when I was about 12. Whether I regret that or not now is unclear, but everything I did at Oxford, and thereafter, was geared at getting into Parliament.

Politics and economics at Oxbridge is quite a well-trodden degree – but it’s often pointed out to me that the current prime minister wields his English language skills and classical education, and that that gives him an advantage. Well there might be truth in that, but there was an element of history in my papers too. My history tutor – who I knew for years afterwards – told me something I’ve never forgotten: “No economist ever makes a good banker. If you want to be a good banker, you have to read history.” I think there’s a lot in that, because it gives you a strategic perspective. It’s not about the numbers, and it’s not just about economic theory nationally. It’s about the ups and downs of life and societal and economic forces – and historians understand those far better than economists.

So in terms of my degree, I feel I learned enough – and I also learned a lot from the practical politics of the Oxford Union. This was at a time when the then Labour government under Jim Callaghan was falling to bits, and Thatcher was on the rise. So the 1979 elections slightly ate into my revision for finals – God knows how I got a degree at all.

It’s interesting to note that Theresa May studied geography, but I think in the end formal education isn’t what it’s all about. Whether you succeed in politics is more to do with your disposition and what you’ve done in life. The problem is I think a lot of people are going into Parliament now without any particular experience – and definitely too little international experience.

I was lucky to gain both in the oil industry. In that industry my best friend was Ian Taylor who died last year – and that friendship, together with the skill I’d acquired in the oil industry, did come in handy in particular when it came to getting rid of Colonel Gaddafi in Libya in 2011. Ian was buying and selling crude oil into Benghazi and we were able to go to the then prime minister David Cameron and explain that if he didn’t follow our strategy, he’d lose the war. Gaddafi was oil, and our approach helped bring him down.

If young politicians ask my advice about appearing on television, I say it’s the wrong question. The trouble is most politicians today don’t think about Parliament first and media second. They have it absolutely the wrong way round.

What I think does matter about being a minister is time management. If you’re not careful, and you don’t administer your day, you can easily be organised by your private office: one of the golden rules of being a minister is always to make sure that you control the diary, rather than let the diary control you. So that means you need to look ahead, particularly for travel and set priorities – and make it clear to your private office that the priorities are as they are, that you will see some people but not others. You also need to explain that you want time to think – or time to call in one of the teams in the foreign office responsible for an area and get into an issue in more depth. So, planning, and not allowing yourself to be just told what to do as a process is the way to do it.

The media doesn’t help any of this. Believe it or not, I’ve never been on The Andrew Marr Show, but I think Andrew has completely lost its way. The questions have become so staid and obvious, and it’s a programme whose time is up. It’s junk because Andrew keeps asking questions to which there can be no clear answer, doesn’t delve deeper and it’s all about trying to trip up the politician. It’s a dead programme.

I did use humour quite a lot in my career – on Have I Got News For You four times in fact. That was absolutely terrifying – they can’t prepare you for that at Oxford!

Photo credit: By Chris McAndrew, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61323695