A look back at Finito World’s mid-pandemic talk with Sir Martin Sorrell who offered advice for the days ahead in April of 2020

Prior to coronavirus, one would have said that Sir Martin Sorrell is a difficult man to imagine confined to his house. With the new normal of global pandemic, we do not have to imagine.

A Zoom interview is not quite the levelling experience one might imagine. True, instead of visiting the 75-year-old’s offices in Mayfair, whose shine and power I am now left to imagine, Sorrell logs on from his central London house. But his energy – which seems part Napoleonic, part East End smarts – is a not a thing to be dissipated on a Zoom call. ‘You look about three years old,’ he says, first up, laughing with typical bonhomie.

Sorrell has been in Covid-19 quarantine like the rest of us for the last few weeks. ‘The house is okay. There’s a bit of outside space which makes it tolerable,’ he says.

Sat in my two-bed flat in Camberwell, his house seems somewhat better than okay. Under a wall of cartoons (‘You can’t see the half of them’) Sorrell will oversee the work of S4 Capital, the digitally-focused firm he founded straight after leaving WPP in 2018, during the indefinite season of lockdown.

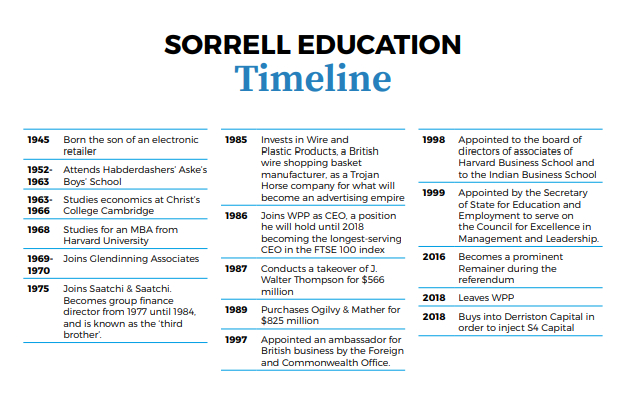

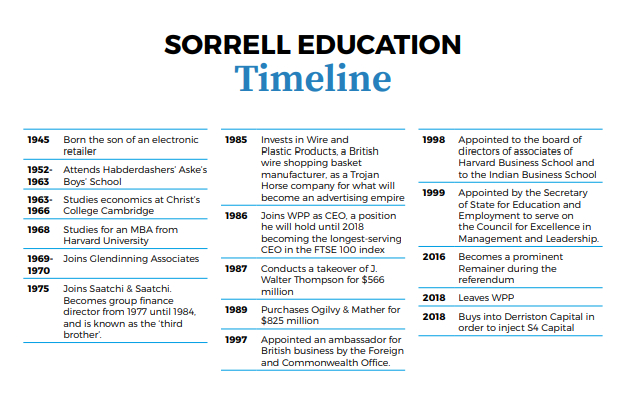

For Sorrell, the coronavirus situation comes across as just another problem that requires solving: he’s seen plenty of these since the early days of Saatchi & Saatchi, through the years of expansion of WPP, taking in the global financial crisis and numerous other shocks along the way.

His bearing is that of a man likely to prosper in this, as in any other era. ‘I actually find I’m doing more work, as there are no interruptions,’ he explains. ‘No breakfasts; no dinners; no surplus travelling. So, on balance I’m more effective and certainly learning more.’

For some, the idea of a more effective Martin Sorrell will be a fearsome notion. Perhaps one such group might be the leadership team at WPP, which Sorrell left under acrimonious circumstances in 2018. It was obviously an unhappy time, leaving the company he had built from scratch. What is perhaps more noteworthy is the swiftness with which he has moved on to the next thing. During our conversation, he refers occasionally to his time at WPP. But he usually does so as a point of reference regarding what he’s doing now at S4 Capital. And he does so far less frequently than he looks forward.

Sorrell founded S4 in 2018, with the mission ‘to create a new era, new media solution…for millennial-driven brands.’ In typical Sorrell fashion, the business has moved fast, acquiring MediaMonks for $350 million in July 2018; MightyHive for $150 million in December 2018; and the Melbourne-based BizTech in June 2019. Sorrell’s modus operandi favours almost hyperactive expansion until scale and geographical presence is established. It seems to work. The firm recently published its preliminary 2019 results showing revenues up 292 per cent from £54.8 million to £215.1 million, and gross profit up 361 per cent from £37.2 million to £171.3 million.

Sorrell cannot prevent noting with a certain glee the morning’s news: ‘I see WPP has suspended its dividend this morning. They were going in the wrong direction before the crisis. But now they have real uncertainty to hide behind.’ How does the present predicament of the firm he founded make him feel? He pauses a moment. ‘How does it make me feel? I think ‘sad’ would be the word.’

DIGITAL FIGHTBACK

But I don’t get the impression that Sorrell ever stays sad for long: he is too pragmatic and tough. Instead, throughout our conversation, Sorrell’s mind whirs about this historical plague moment – how best to navigate it, not just on his own behalf but on behalf of the 2,500 people S4 Capital employs. ‘If I’ve got 2,500 people in the business, and on average three in each family, that makes 7,500 dependents. At WPP it was 200,000 including associates – so that was 600,000, and a different scale – but you feel responsible for that.’

For years now, Sorrell’s mantra has been digitisation. You might say that in his mid-seventies he is an unlikely evangelist for the great tech firms both in the US and China – but then, like Oscar Wilde, Sorrell has never pretended to be ordinary.

And it’s the digital world which is impressing him during these coronavirus times. ‘The technology is very good,’ he says, bullishly, having been particularly impressed by an online seminar he participated in post-lockdown with Harvard Business School. Sorrell was swift to implement their recommendations. ‘We instituted our crisis group Wednesday last week [the first week of lockdown]. It’s very brief but it meets across the business. Every day we cover San Francisco to Sydney. It might have been more in the beginning but now it’s 15 minutes.’

Regarding the immediate economic future, Sorrell already has a clear sense of how the virus will play out: ‘I’m of the V-shaped school. You feel it in the markets already. It’s terrible, it’s shocking, it’s catatonic – a lot of companies will go down. We were dramatically underprepared.’ The sentence hangs there as if it might want to turn into an optimism, as indeed it does: ‘Q2 will be horrendous, Q3 will be tough but better, and Q4 will be a recovery,’ he says.

But it is in the nature of these uncertain times to be continually oscillating from hope to worry. Sorrell is no different, adding: ‘But a lot of companies will have gone to the wall by then. In our industry, a lot of highly-regarded production companies have gone. B-Reel, for instance – very good work, good people. Just gone. I think it’s going to be very difficult. This is a Darwinian culling.’

LIGHT RELIEF

I assume this refers to the business environment but it might also refer to the wider health story of which we’re all so acutely aware. A passionate Remainer in what we must now think of as the previous era, Sorrell has long since kept a businessman’s critical and bemused eye on politics.

This time around, he has observed with bafflement the zigzagging government strategy. ‘I do find the government policy a little bit strange,’ he explains. ‘Going into this, they knew the head count – if I can put it like that – could be 300,000. This wasn’t new information. I think at a certain point Dominic Cummings and Boris Johnson changed their minds from an approach which basically entailed culling the herd to create herd immunity, to one of lockdown. They suddenly reversed their approach; I’m not quite sure why.’

The CEO is also illuminating on the Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s rescue programmes for businesses. ‘They take time to implement,’ Sorrell says. ‘I spoke to someone who’s heading the UK Finance Initiative yesterday: on the loan schemes, you have to give personal guarantees. I have a friend who’s 75: he’s not going to give personal guarantees on a business that could go belly up. A lot of this stuff will be deployed where it is least needed – to large businesses and not to small businesses.’

And what about Donald Trump’s view that the cure is worse than the disease? ‘I’m not one of those who thinks we should have gone down the herd immunity route. But when you’re in a leadership position, you tend to overegg things. Boris Johnson overeggs it; Dominic Cummings overeggs it; and the media focus magnifies it to such a degree that mistakes are made. People who lead companies and government departments err on the side of caution.’

Sorrell adds: ‘And the enquiries into it will be everlasting and all the civil servants are terrified – and ministers are terrified – of investigative journalists who will be poring over the entrails. That makes people overcautious in the wrong way – as it stops them from making decisions when speed and agility is wanted. You see this in corporations – the lack of agility is huge.’

FACING THE STRANGE CHANGES

Beyond the immediate crisis, Sorrell discerns some changes which are likely to remain. ‘It will be an acceleration of what was already there. Consumers were moving online; now they’re going to move faster.’ Sorrell gives an example. ‘Harvard Business School has a virtual classroom. So now, with Zoom, you’re on a screen with me, I’m on a screen with you. Imagine 80 times that with three professors in the pit. You can email in, you can text in, you can raise your hand technologically.’

So the virus will make us think differently about gathering together publicly when we don’t absolutely have to? ‘Before all this happened, you’d have to go to Atlanta or New York for a call like the Harvard one. But we did it in an hour and a half without all the concomitant waste, the travel, climate change.’

Sorrell also expects there to be other profound structural changes to our leisure. ‘I am on the International Olympic Committee (IOC) commission, and I’ll probably go to Japan next year. But will I go to the Superbowl to see the Patriots with 100,000 people there? Because one thing’s for sure, Covid-19 will re-emerge. We may have a vaccine to deal with it – or it may come back in the cold weather of Q4 this year which will make the recovery more difficult.’

Again, our conversation keeps swapping cautious optimism for melancholy pessimism. Our current condition is to be continually subject to revelations about how the virus will affect some hitherto taken-for-granted aspect of our life. Sorrell, you feel, has done more thinking than most, but he still has some thinking aloud to do. ‘This summer, where will people go for holidays? Very few people can take private planes, and there will be attendant risks to flying. There was a newsreel of the Chinese travelling in China. Everyone’s dressed in these spacesuits. You turn up and you’ve got these face masks. You’re assigned a seat before you get on, distanced from everyone else. Behaviour will change.’

And the wider media landscape? Sorrell is more decided on that one. ‘It will accelerate media owners’ use of digital and also accelerate the decline of linear TV. I was on a call yesterday with a Morgan Stanley analyst. Of course, the tech giants will feel the short-term impact on SMEs, but in the long-term it will result in Google and Facebook having a more dominant position. Imagine the data that Amazon is buying on consumer buying patterns: it will give them a huge data advantage. The same will be true for Tencent, AliBaba and Tik Tok in the east.’ This in turn feeds into Sorrell’s business model at S4: ‘We will benefit as long as we get through the next few quarters’.

SCHEMES, STRATAGEMS AND SPOILS

At other times, one has a sense that the reckoning of Covid-19 has created in Sorrell, as in most of us, a desire to pause and reflect. This sends our conversation – perhaps to our joint relief – away from the present crisis to wider questions of business.

So how to be effective in business? First, he says, you have to learn how to manage teams. ‘Even at small scale, you have the same issues around siloes and fiefdoms and people looking with blinkers,’ he explains. ‘When you have two people in a company, you have a cooperation problem. To get 2500 people to think as one, or to leverage whatever knowledge the 2499 have – that’s the game. If you can get people to share knowledge and insight, you have a much more potent organisation.’

Sorrell is in full flow now: you have a sense that these are the issues he has turned over in his mind for 50 years, and he enjoys sharing his knowledge. ‘My favourite question to anyone I’m talking to is: ‘What’s your biggest problem? The answer in most cases is lack of agility.’

What does he mean by that? ‘The siloes, the empires, and the fiefdoms within big organisations’. Sorrell is often known as a legendarily hands-on CEO, and this is sometimes presented as a flaw. But it might also be an aspect of impatience with barrier and impediment coupled with a strong sense of responsibility towards the workforce and its dependents.

Sorrell also recognises that talented people can present problems of their own as much as those who aren’t performing. ‘Good people are by nature not cooperative,’ he explains. ‘There are very few good people who work well in teams – and understandably so. They have good track records, and tend to think they’re right and don’t take advice easily.’

The job of a CEO is to get everyone facing in the same direction. ‘Implementation is very difficult in large and complex organisations,’ he explains. ‘You’ve got functional matrix; geographical matrix; brand matrix. It’s very difficult.’

So how to conduct the orchestra? One part of the answer is incentivisation. ‘At S4, we all own big chunks of the company. The WPP employee ownership schemes probably amounted to about three or four per cent. At S4, we’re smaller obviously, but about 50 or 60 per cent of the company is owned by people who work in it.’ This is an area too, where Sorrell’s education – Sorrell studied economics at Cambridge – has been helpful to him in his career.

‘At Cambridge, there was a book by a left-wing economist called Robin Marris – a left-wing economist – called The Theory of Managerial Capitalism. In the capitalist system, there is a separation between management and control. Managers manage; shareholders control – but there is a split between the two. Out of that, you get the view that all you need is share ownership: if people own shares in the company then their mindset is different.’ Is that his view? ‘Well, it can produce too short-term an attitude but broadly I don’t disagree with that. In WPP, in the early days, I always insisted people put their money where their mouth is. Interestingly, after a couple of plans, the institutions preferred us either to pledge stock we already had or just waived the need to put cash in. That was a terrible mistake. It’s like Warren Buffett’s comment on share options many years ago. You wouldn’t give an institution a call on your stock for 10 years at zero cost so why do you give it to management?’

HIRING AND FIRING

The other way to keep a company in shape is to get the hiring right. To those who might be ruminating on a magic hire, Sorrell has this warning: ‘I used to call it the Jesus Christ syndrome.

The person running this area of the business is no good. We should get rid of him or her. And I’ve got this fantastic person I want to hire.” Then the person comes in and three months later, Jesus Christ didn’t walk on water!’

Sorrell also argues that talent departments can get it wrong at both ends of the spectrum. ‘The hiring process is often too cumbersome or else it’s too intuitive,’ he says. ‘You either put somebody through 20 interviews, which anyone who’s good will not tolerate, or you have one interview and that person becomes a hero or heroine – a salvation. Advertising businesses are notoriously bad at hiring.

Individual predilections or preferences overcome what you should or shouldn’t do.’ He adds: ‘Another problem is to segment human resources and talent from the rest of the organisation. You shouldn’t rely on your head of HR to hire good people. The head of HR might supplement the list, but you should know who you think would be good to do x, y or z from your knowledge of your industry.’

Somewhere in here is the key to Sorrell’s success – the need to be hands-on isn’t some bizarre need to micromanage but a sort of prudent due diligence, and a tacit acknowledgement of the complexity of the job. He draws the conclusion: ‘People are an investment not a cost – and we spend so little time maximising that investment. sixty per cent of our net revenues are invested in people. Our revenues are £400 million, and we represent £250 million. At WPP it was £20 billion, so £12 billion went on people. But most people think much more about how we should invest in computers.’

And this, incidentally, is why government often moves with such little – to deploy one of his favourite words – ‘agility’. ‘In government, you don’t have the commercial levers or incentives: what you get is a splintered mess,’ he says.

HANG-UPS

Our time is nearly up. Towards the end, Sorrell strikes another note of cautious optimism: ‘I’m sure there will be a relief rally in the sense that when people are released from all this purgatory, there will be excesses. But I was talking to a client last night and I said, “I’ll call you in Q4 and we’ll say we overegged this.”

He continues: ‘I look at in a historical context. HIV has killed 36 million people. The two big flus killed 1 to 2 million. I’ve got a lot of friends in Brazil who are terrified about what the impact of corona is on the ghettos. We’ve lost proportion. That sounds callous, every life is important.’

Such are the times we so suddenly live in: we wish to retain optimism but we have taken a collective decision to endure economic hurt in order to protect the vulnerable. It is the hardest time the nation has known since World War Two, and yet all our technologies remain intact giving – at least for the time being – an undeniable flavour of technological affluence even to this unprecedented stricture.

Deprivation is still allied in a certain sense to plenty: we are in our homes, but many of us still eat, drink and are entertained to standards which would be the envy of a Renaissance king. We retain a sense of our intelligence and scientific skill, and the power of the economy which the likes of Sir Martin Sorrell have been instrumental in building. But we also know all over again the scale of the obstacles – of disease and nature’s indifference – which we had to overcome to build it all in the first place. There are no guarantees of our success; it’s up to us.

Perhaps that’s why Sorrell – so self-reliant, and capable – is someone we should especially heed in these times. We need the likes of him as we have never done before. ‘Someone sent me a diary from the great plague,’ he tells me near the end of our call. ‘It was a world of self-isolation; there was the Peak District village of Eyam which cut itself off for a year. This is nothing new.’

So nothing new – and everyone keep calm. Wisdom, like crisis, can often have an antiquated flavour. And with that, instead of the handshake at the lift, we say our Zoom goodbyes, and Sir Martin disappears out of my computer back into his improbable life.