Christopher Jackson is impressed with the art of Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood at Tin Man Art

The Internet may have wrecked the opportunity for tactile nostalgia. When Radiohead’s OK Computer came out in 1997, I experienced it on CD and part of that experience was to be confronted with the physical object itself in the shape of the artwork. There was nothing quite like the album cover – allusive, weirdly beautiful – to prepare you for the album itself.

Had the Internet not been invented I’d probably have kept my CDs and be able to find the cover. Now I have to google it. Alternatively, I can look at the new pictures of Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, which have been showing at a two part exhibition ‘The Crow Flies’ at Tin Man Art.

These works have been done in collaboration and are remarkably good. The first picture which catches my eye is ‘Let Us Raise our Glasses To What We Don’t Deserve’ – which sounds perhaps unsurprisingly like a Radiohead song title. This shows what might be a sun dominating the canvas, with tendrils coming out of it. Beneath it, a green world told in oil paint seems to be mapped in some way: patterns recur as if they have been pinned down as having special significance. The effect of the oil is to create the memory of its application: it feels as though we can see its movement into place on the canvas.

Let Us Raise Our Glasses To What We Don’t Deserve

“That was what I found incredibly exciting. It just stays active for so long,” says Yorke in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition. He draws a lesson about the similarity between oil painting and music: “I became so conscious of the fact that the two processes are almost exactly the same.”

The first thing you sense with these works is that a lot of thought has gone into it – that there’s some been some heavy-lifting behind the scenes. Donwood tells me: “Our aim is to make work that functions, that does what it is supposed to do, what we intend it to do. Which is, in essence, to convey meaning. Although what that meaning actually is must remain unclear. It’s necessarily quite vague, otherwise we would just write slogans on billboards and leave it at that.”

I mention that there is a playfulness to ‘Let us Raise our Glasses…’ and Donwood agrees: “One of the influences in these works was the way that Mediaeval paintings have no sense of perspective – if something is not important, it’s small, if it’s vital and interesting, it’s huge. This idea of representation is kind of funny to us, because we’re used to perspective and photography, so to us it looks playful, but it’s just another way of looking at things. All painting is play to an extent; it’s something all children can do, and some children just don’t stop doing it.”

These pictures therefore provoke a range of responses – and you know you’re in the presence of exciting art when it’s making you smile at the same time as it’s making you think.

The large sun in ‘Let us Raise our Glasses’ cannot help but evoke climate change – the psychological nature of a hot day has changed these past years to become a cause for foreboding.

Would Donwood and Yorke shy away from having these works incorporated into that conversation? “Not for a moment. It’s hard just to get up in the morning without thinking about our rapidly changing climate, and that’s putting it incredibly mildly,” says Donwood. “Everything that we rely on, not just for our amazingly comfortable way of life – clean water, electricity, somewhere to live, safety, freedom from harm – all of these things – everything, absolutely everything is at enormous risk from the breakdown of the patterns of climate that have made civilisation possible. There’s no way anything can happen without the menacing spectre of annihilation looming over us.”

Yorke is also comfortable with these sorts of interpretations: “I’m completely incapable of creating anything without a kind of narrative.” But he adds a post-modernist twist to this, explaining how narrative is rarely linear – and more than that, that the viewer will make their own narratives independent of the artist’s intention. “I see narrative happening in different kinds of ways. You make associations because you need to make associations,” he says.

Their art, then, is about freedom – it strikes me as an exciting moment in the history of art where the initiative is seized back from the photograph. Yet there’s a paradox here too, because by working in collaboration each has surrendered what we have come to think of as the freedom of working individually.

I ask whether there is a competitiveness at work here, but in asking the question realise that I have underestimated the long history of working in bands which Yorke has had, and how genially Donwood has fitted in with that ethic. “Not really,” Donwood explains. “We used to take turns at a canvas until one of us ‘won’ it; which is to say that one of us would have the better way of continuing with whatever was emerging, but for these paintings we’ve worked together on the pictures at the same time, and we realised quite quickly that each of us had ingredients which we were more suited to using, techniques of painting or ways of depicting images, but this time these energies were complimenting rather than battling against each other. Neither one of us could have made these pictures alone.”

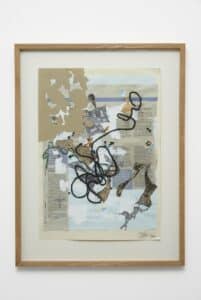

I say that I particularly like the picture ‘Membranes’ where the main portion of the canvas is taken up with what might be intertwining rivers – or alternatively may be, as the title suggests, a landscape plucked out of the land of the very small – the universe of the cell or the subatomic particle.

Bob Dylan once said that all his songs ultimately meant: “Good luck, I hope you make it.” In these pictures there is a gallant sense of mysteries being mapped. Donwood tells me about its genesis: “These paintings were made in two sessions; the first from some time in 2020 (I forget exactly when, but it was back in that strange lacuna which was entirely coloured by the coronavirus) until early in 2022, and the second from early 2023 until the summer of the same year,” he recalls. “The first series became a sort of collection of navigational aids, a set of maps or diagrams of somewhere that had never existed and never would. The second were, perhaps accidentally, some kind of depiction of what you might find if you followed those maps.”

Membranes

So how did’Membranes’ evolve? “It wasn’t planned in any way – none of these paintings were – but it became a sort of deluge, a flooded landscape, a floodscape really, a rushing tumult that was in the process of swallowing everything it could. Or at least, that’s one way of looking at it. At the same time it’s a huge sound, an immense outpouring of volume that drowns out everything else that might be heard.”

That reminds us that music is never far from the pair’s collaboration: it is inwoven both in the context of their friendship and in their methodology. But Yorke and Donwood differ here too: “Obviously Thom is a musician and perhaps less obviously I am most definitely not. I can’t play music and I don’t begin to understand it, but I can listen to it, and I have always listened to it. It’s always affected how and what I draw and paint.”

Yorke’s music continues to mature – in 2023, he debuted a new band in collaboration with Johnny Greenwood and Tom Skinner called The Smile. Their debut album is A Light for Attracting Attention. Do they listen to music while they paint? “The results of making art while listening to classical music are completely different to what they would be if you were listening to jazz, or heavy metal, or someone telling you a story. While we were making these pictures we listened to the music that was being made, the music that would be on the record that would be inside the sleeve that had the artwork we were making printed on it – so we heard a lot of The Smile. But it wasn’t finished music because it was being made at the same time as the pictures, so neither were finished but both were on that trajectory. We also listened to quite a lot of techno.”

For Yorke, something of the process of The Smile has found its way into these paintings: “Because it is a three piece, things would happen extremely fast and you didn’t really know what it was until you came back. It’s very fast. It’s very fluid.”

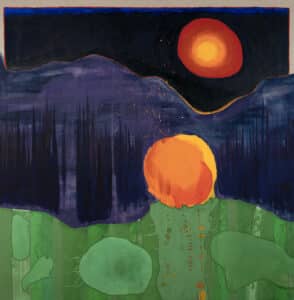

One example of this is the magnificent picture ‘Two Moons’, where I find myself particularly drawn to the sparks which fly out of the moons, suggesting some sort of charge or quickening energy. I ask whether Donwood and Yorke painted these works quickly to capture a rapid creativity or whether the process was more careful than it might appear.

Donwood is enthusiastic: “This, like all of these paintings was one that revealed itself as it came into being. I didn’t know what would happen; I didn’t know there would be sparks, but right at the end of making the picture it was very obvious that it needed that explosive energy – but just enough, not too much. Any more would have ruined it. It was, counter-intuitively, a really careful and considered action, but one that had to look fast and energetic.”

Two moons

I suggest to Donwood and Yorke that the hardest thing about abstract art is to know when it’s finished – when you’re in a process of complete invention, there is no natural moment to finish as there is when you’re seeking to render a literal description of the world. “This is something very difficult – or more precisely, very nearly impossible – to explain,” Donwood admits. “Mostly because I don’t understand it myself; I know for sure when a picture isn’t finished, when it needs more, or when it needs change. But I frequently don’t know what that ‘more’ or ‘change’ is, so there’s necessarily a lot of experiment, much trial-and-error. Mostly error. It’s very useful not to work alone because a second opinion is fantastically helpful when you’re a bit lost.”

This then is another instance where collaboration can free you of the bafflement which accompanies creativity. “I think it’s a question of balance in the picture – I can’t define what that balance is, but it’s probably something like the difference, when you’re out on the world, perhaps away from everything, between a view that excites your senses and a view that means nothing that doesn’t register as ‘a view’.”

So what has been achieved here? I think it’s the transmutation of the seen world into something which answers to the complexity of our experience. Take for instance ‘Somewhere You’ll Be There’, where we find a sense of the earth’s upwards force and the volcano-like shapes themselves seem to undergo a metamorphosis into figures – ghosts even.

Donwood explains: “The notion of inanimate objects or landscape features coming to life is something I am fascinated by. Sleeping giants below the hills, being watched by trees, your surroundings reassembling themselves while your back is turned – I love these ideas. The ghostliness of our surroundings, a kind of hauntology of everyday life… In many pictures that we’ve made there are eyes where perhaps they shouldn’t be. It’s also startling how two simple marks can give such a sense of watchfulness and of a kind of life to almost anything.”

Somewhere You’ll Be There

This is marvellous – and speaks to a joy in the work which we might not always feel we’re hearing on a Radiohead album. I ask the pair whether they’re happy during and after painting, or should we be thinking more in terms of struggle and surmounting obstacle? “I don’t think anyone should be thinking too much in terms of struggle or of surmounting obstacles! Life is hard enough as it is, no? But as to whether I feel happy, that’s kind of a little too far in the other direction. There’s definitely a form of satisfaction when a picture is finished, and there’s certainly a kind of joy when everything is going well. This is always tempered with the frustration, misery and sometimes acute depression and what feels like depthless melancholy when things are going awry. I guess it’s the same for all work of this type. Swings and roundabouts, hey?”

Yes, but after all that fluctuation in experience, it seems that, if we’re lucky, the artist gets us to a worthwhile endpoint which is the picture itself. I hope these pictures will continue to attract viewers and critical attention; they certainly deserve to.

As the Crow Flies: Part II is at Tin Man Art from 6th December to 10th December