Waterstones CEO talks to Georgia Heneage about the threat of Amazon, the pandemic and the future of the high street bookshop

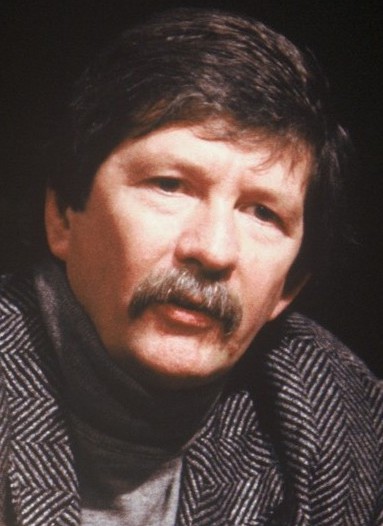

Despite the number of obstacles which stand in the way of high street bookshops thriving, bookselling giant and CEO of Waterstones James Daunt is infectiously optimistic. His passion for the paperback and belief in the physical experience of standing in a bookstore is compelling, even over Zoom.

High street retail was stuck in a mire long before the mass closure of shops over the past year. The pandemic has, of course, been the final nail in the coffin for many shops across the country – apart from those like M&S, John Lewis and Next all of which, Daunt points out, have had the resources to pivot online and create “more modern and dynamic” systems. This response has placed further pressure on other businesses reliant on the footfall: “It’s a kind of self-perpetuating domino effect,” Daunt says.

Bookshops, one might think, have not escaped this vicious cycle. Daunt, 57, points out that they’ve also suffered from the government’s “perverse definition” of what constitutes an ‘essential’ shop, and been in direct competition with those that have been able to stay open and sell books, like WHSmith and supermarkets. Like the majority of other shops, Daunt warned back in January of this year that Waterstones faced closures due to continuously high rent rates.

But bookshops have also bucked the trend to some extent, both during the pandemic and pre-pandemic in what was sometimes called the slow death of the High Street. Daunt has been highly praised for leading Waterstones during what have been dark days for bookshops. And if the brief periods of reopening in the past year are anything to go by – and Daunt says they’ve been “very busy” during those times – bookstores have a better future than has often been predicted.

Other kinds of retailers, though, he’s far less optimistic about. “It’s a savage environment,” he says, ever the fierce competitor. “If you’re not on top of your game, then you disappear.”

Daunt is also keen to point out that this is the unique nature of bookselling. “I think the problem is that other retailers don’t have the same benefits as bookshops. At the end of the day, it’s actually not that much fun to go into a shoe shop or clothes shop. The great thing about a bookshop is that everybody likes being in it, whereas most other shops appeal to a narrow demographic.”

Despite the looming threat of Amazon on the book world, Waterstones has been “able to prosper” over the past ten years and sales have been gradually increasing. This, says Daunt, is mostly down to the experience created in-store, which remains the main point of differentiation between Waterstones and Amazon, with the latter providing neither customer-facing relations nor a warm “social” environment.

“Bookshops are nice places,” Daunt continues, “where you can find a book by recommendation or have the serendipity of picking up a book and thinking ‘Oh, I’ll read this’.” And the book you buy is “just better”. “I truly believe that there’s pleasure in walking out of a bookshop with a bag and feeling the weight of the book. You feel kind of virtuous – like you’ve almost read it.”

If Daunt had to point out the singular most important ingredient of bookshops, it would be the people. If at the start of the 21st century everything was about “cutting costs and getting rid of staff”, the past decade has been marked by reinvesting in the people of the industry. “The personality of your shop is, at the end of the day, embedded in your staff. If you invest in knowledgeable people who care about what they do, you’ll run a much better bookshop: this is what underpins the strength of Waterstones.”

And of course, this is another differentiator with Amazon, which has, in the past, been criticised for bad customer relations.

Waterstones dominates a quarter of the book market, and has been able to thrive in recent years. But what of smaller independents, who collectively hold a mere 3 per cent share of the market? “The good ones are actually in a better position than chains like Waterstones,” Daunt says, pointing to the backing such shops receive from their local communities. And again, it’s “survival of the fittest”: “If you’re good enough, and you genuinely create a nice environment, you’ll be fine. The rise of Amazon actually weeded out all the weak ones, and it’s the good ones that remain,” Daunt argues.

The other tech-oriented threat facing paperbacks is, of course, Ebooks. But if they surged in popularity around 2014, their retreat back into the shadows is testament to the difficulty of actually replicating the feel and texture of a book. “I can’t see how that’s ever going to be replicated in a way that also gives you all the other tangential pleasures that come with owning a book, or having a bookshelf- they are almost a diary of your life,” says Daunt.

The really powerful new trend permeating the book world is Audiobooks, which has boomed in popularity – especially amongst older readers, with downloads increasing by 42.5 per cent in the first half of 2020 alone. Daunt is now also CEO of Barnes & Noble, which Elliott Advisers bought in 2019 for a reported $683 million, and the firm has started to set its horizons on the medium, with the launch of its Nook 10 HD tablet.

Even so, Daunt doubts whether Waterstones will be able to follow suit. “The market share is tiny, because at the end of the day Amazon will always undercut. They invest much more, and they’ll always have the advantage of having created the market in the first place. Everybody else is just playing catch up.” He says that unless he can work out some way of “piggy-backing on the Barnes & Noble capability which, with different publishers and associated rights, will be complicated, Waterstones won’t be able to launch an audio subscription service.”

Despite all this, Daunt remains ever-positive regarding the prospects of the book world. “There’s still the majority of people will prefer reading physical books. I think you just leave Mr Bezos to make all his money, and the rest of us can just prosper at what we do.”

And if recent book-sale figures during the pandemic are anything to go by, appetite for reading is as voracious as it has been – if not more so. Daunt sees this as a pivotal moment for reading – a bit like the inception of the Harry Potter books, which changed many people’s book habits irrevocably and led to a “permanent elevation” of reading. “It may not stay at this level, but I’m optimistic it won’t fall back to the old level. I think there will be a permanent shift upwards.”

That the majority of soaring book sales during the pandemic were non-fiction titles points to the fact that people are thirsty to learn about the world around them- a world increasingly beset with existential issues and polarised political debate. People are “energized”, says Daunt, “and books play a massive part in that.”

Though for many the biggest single threat the world faces is climate change, Daunt says racial issues brought to the fore by the Black Lives Matter protests will be what people WILL remember of this year. How does he know this? “Our bestsellers last year were books essentially about race and inequality. And our market share as a bookseller was dramatically higher (up to 60%) on those issue-led books. People wanted to come into a bookshop and find out what works.”

Reading – and if we take Daunt for his optimistic word – bookshops, too- are a reflection of the interests, passions and problems of an entire society. Daunt puts it simply and exactly: “Books sit at the heart of what matters.”