Has poetry been demoted on the national curriculum? If so what does that mean? And do poets really know anything about work? George Achebe did a little digging

When Finito World spoke to former shadow schools minister Margaret Greenwood recently, she recalled an episode during the 1970s, before the national curriculum even came in. Greenwood was teaching a particularly difficult class in secondary school. “It was a real challenge, but then I hit on an idea. I was going to give them all poetry books to read to themselves, and I was going to say: ‘This is a quiet reading lesson’.”

It was the sort of inspiration which could be permitted to strike in those comparatively targets-free days. What’s more, it worked – though some of her fellow teachers were sceptical. “I remember one teacher looked at me askance and said ‘You’ll never get them to sit still’,” Greenwood continues. “But I went to the library and got all the poetry books and dished them out and explained that this was what we were going to be doing every Tuesday.”

The strategy took time to yield results. “It was fascinating. At first, there was a struggle and a bit of resistance. Then they got into it. We need to let teachers be the professionals they are.”

It’s a story about teaching, yes, but it’s also a tale about poetry. It posits the idea that poetry is capable of crossing boundaries, of overcoming indifference – and ultimately that a poem – even a line of poetry – can alter the course of a life.

And yet if you look at recent government policy, it seems rather to tend in the opposite direction. It began with a storm last year – in the world of poetry, a storm usually amounts to a single article in The Guardian. In this case – a measure of the seriousness of the issue – there were two articles in The Guardian.

The cause of the storm? This was to do with Ofqual’s decision to make poetry optional at the GCSE level. The ruling states that for this year students must compulsorily take a paper on Shakespeare, but that they can choose two out of three from the 19th-century novel, a modern drama or novel, and poetry. Poet and teacher Kate Clanchy summed it up: “For the first time, poetry is a choice.”

The indignation – in Clanchy’s article, and also evident in a similar piece by poet Kadish Morris – was open to some objections. In the first place, Shakespeare is nothing if not a poet – and has for five hundred years proven a pretty good ambassador for poetry. Meanwhile, much modern drama – especially TS Eliot – deals in verse, and its prose dramatists – one thinks of Pinter and Beckett – tend to be poets as well. So it wasn’t quite the dagger through the poetic heart which it was reported as.

Secondly, teachers are, of course, able to teach poetry anyhow regardless of what Ofqual says. When I spoke to a secondary teacher friend, who asked not to be named, she said, “It’s not like my children aren’t exposed to poetry; they are. All this sort of thing does is demoralise teachers.”

When Finito World approached Ofqual for an explanation, a spokesperson further explained that the changes are temporary and “designed to free up teaching time and reduce pressure on students”. In other words it’s a specifically pandemic-based change, which should be repealed once we return to normal. Even Clanchy seemed to admit this in her article: “Plenty of teachers will stick with the poems, especially if they’ve already studied them,” she wrote.

In addition to this Ofqual pointed out to us in their statement, that exam boards retain the freedom to add to the common core if they wished. Meanwhile, the Department for Education didn’t reply to our request for comment.

So is the whole thing a storm in a teacup? Well, not quite. In the first place, Clanchy surely has a point when she draws attention to a double standard: “The content of double science – the popular three-in-one science GCSE – is presumably also, as Ofqual says of poetry, difficult to deliver online, but Ofqual isn’t telling teachers they can pick between chemistry and biology next year providing they stick with the physics.”

It’s a reminder that this decision feeds into poetry’s worst fears about itself – about its sliding into irrelevance. This is probably misplaced: when we have a funeral or a wedding – that is, when we really want to say something important to one another – we tend to reach for the music and springiness of poetry ahead of prose. That will probably always be the case.

But there wasn’t a similar storm over the optional nature of drama or the Victorian novel to quite the same extent. In the first instance, in an age of theatres closing, drama writers are more concerned about their works being put on again than they are about their texts being studied. And the Victorian novel, regularly adapted for film, seems invulnerable.

Poetry is different; it feels fragile. As Alison Brackenbury, one of our greatest living poets told Finito World: “Many people only know – and value – those poems which they encountered at school, especially if they learned them by heart. If they don’t come across poetry which appeals to them in their curriculum, the one chance may be gone.”

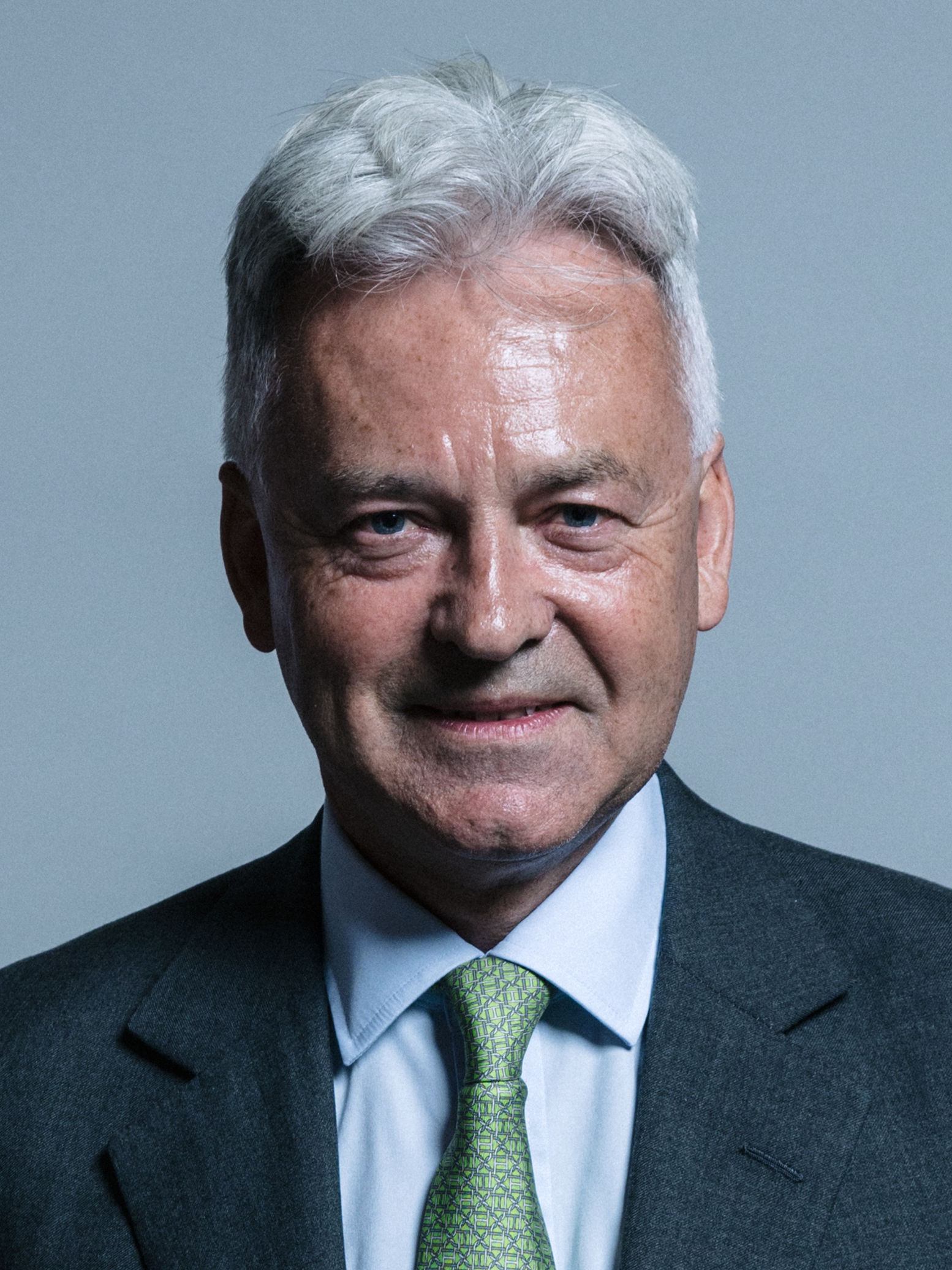

The Chair of the Education Select Committee Robert Halfon MP also expressed his worries: “In some ways what the government has done is understandable because of Covid. There are worries that with the Fourth Industrial Revolution 28 per cent of jobs might be lost to young people by 2030, and so the curriculum has to adapt and change.”

But then Halfon pauses, thinks and delivers his verdict: ”Having said all that, poetry and literature are one and the same. In my view, you can’t promote one over the other.” He is also uncertain over whether it’s really such a temporary thing. “DfE is saying this is a temporary measure, and it’s designed to help take the strain off pupils because poetry is perceived as difficult. But temporary measures can become precedent and poetry trains your mind in a very different way. If this becomes permanent it would be very worrying.”

It can seem to some that since the hyperactive tenure of Michael Gove as Secretary of State for Education, aided and abetted by Dominic Cummings that “English has been shrunk, confined and battered into rote learning and stock responses,” to use Clanchy’s phrase.

Halfon agrees: “Culture has an absolutely important role, not just in the economy but in our society and shaping our lives. It’s not just good for our learning – it’s good for our mental health, and it’s good for expanding our horizons. We don’t want to be a society of Gradgrinds where all we want is facts.”

Halfon is reminding us that just at the moment when we are all looking at our mental health, the government appears to be demoting the branch of human affairs most designed to improve it.

Christopher Hamilton-Emery, the poet and former director of the immensely successful Salt Publishing adds that the question of poetry’s status on the curriculum is relevant also to the increasingly discussed area of social mobility: “There’s a wider context to this and that’s the way kids come into contact with poetry, or orchestral music, or ballet, or opera, or theatre. In this sense, education is the gateway, the space that gives permission to children, and in this context there’s a political and egalitarian component to this debate around poetry.”

But Hamilton-Emery adds, only half-jokingly: “I also recognise that poetry is a pain in the arse. Yet it’s meant to be awkward, tricksy, resistant to authority, dissonant – things that are hard to teach and accommodate, things that can’t easily be measured or controlled. Poetry provides a critical citizenship and, I think, helps form the unity of the person and offers a living communion today and indeed through history.”

This goes to the heart of the matter – the sense that the Conservative party represents authority, and that poetry is somehow being punished for being anti-establishment. Of course, these sorts of generalisations can never be the whole truth – even if there is often some truth in them. You could probably make a case that from Philip Larkin and WB Yeats to TS Eliot and Ezra Pound, there were more ‘great’ right-wing poets in the 20th century than among their left wing counterparts.

And yet one wonders whether there is a sense in which in our technology driven, factual lives we have ceased to credit marvels and insodoing come to see poetry as somehow wishy-washy, and even insufficiently grounded in the commercial. Tishani Doshi is a world famous writer and dancer who continues to make poetry the centre of her life. She speaks revealingly of the poetry and the administration sides of her being: “I studied business administration and communications before ditching it for poetry, so I can get around economics and accountancy alright, but that’s not to say I thrill in it. I move in waves. Sometimes I’m terribly productive about everything – to-do lists and all. Other times I want to be left alone to watch the flowers.”

It is this idea that the government no longer wants us to watch the flowers which riles people so much when this kind of decision is made. But Doshi is adamant that we need a more nuanced conversation: ‘One of my first jobs was to teach an introduction to poetry and fiction class to students at Johns Hopkins University. It was a required class, most of my students were pre-med or engineering. I like to think as a result that in future dentist waiting rooms, there may be a volume of Elizabeth Bishop lying around, or that someone designing a bridge might dip into the poems of Imtiaz Dharker for inspiration.”

Halfon agrees: “My reading goes into my subconscious. It helps me when I’m writing articles – I may think of things and quote things and use metaphors. It just infuses my thoughts and the way I think. Something permeates like a beautiful stew that’s been cooking for a long time – and it always tastes much nicer on the second or third day of eating it.”

Doshi adds: “I don’t know what the UK government’s motivations for demoting poetry are, but I hope usefulness was not a factor. Everything is connected. I can’t imagine any kind of life that doesn’t need the intuition and imagination of poetry.”

WH Auden once wrote that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’, adding that it ‘survives in the valley of its being said, where executives would never want to tamper.” And yet in being so lofty it has made itself vulnerable to demotion.

Yet the poets one meets tend to be tougher than you might think – they cannot afford to be Keatsian and head in the clouds. They have to work. We’ll update on progress in a subsequent issue.