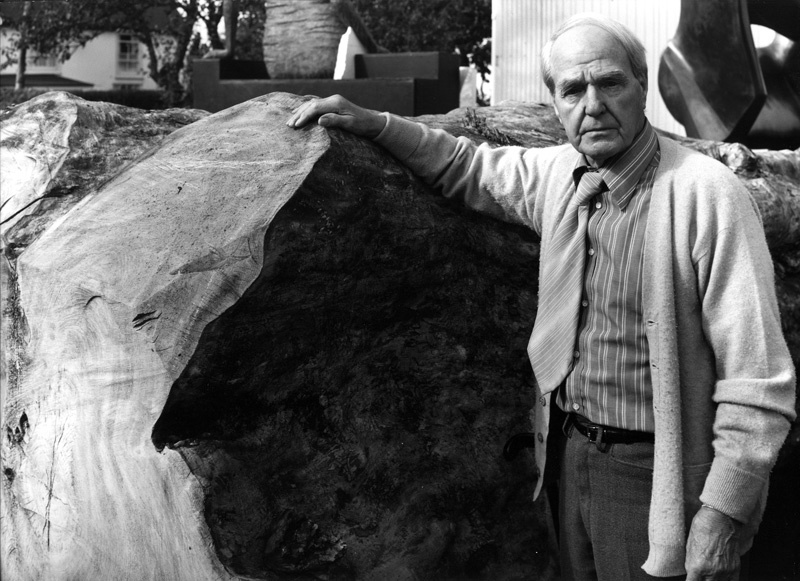

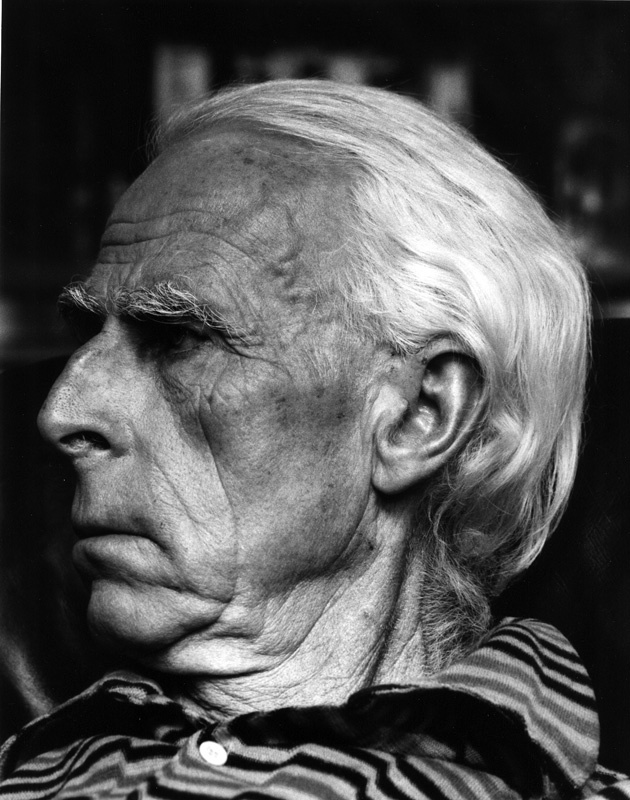

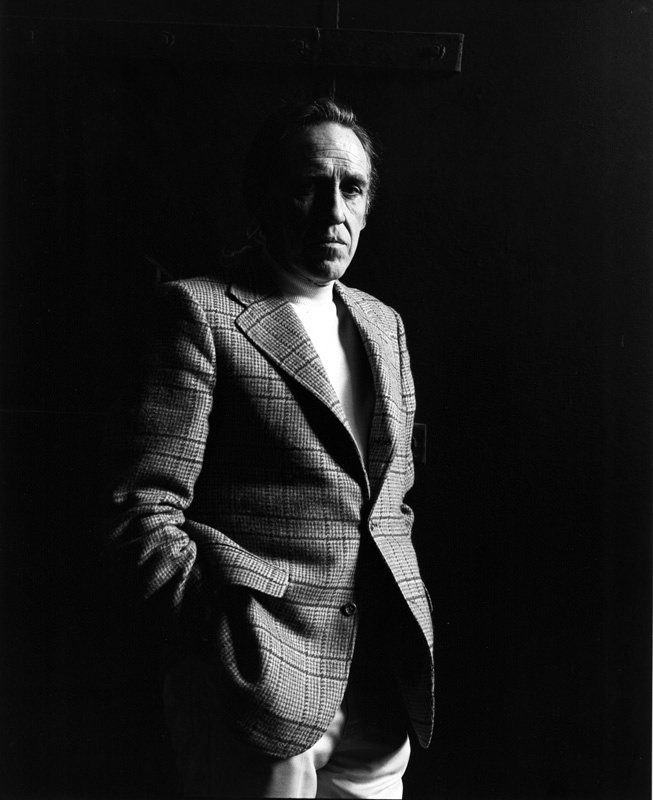

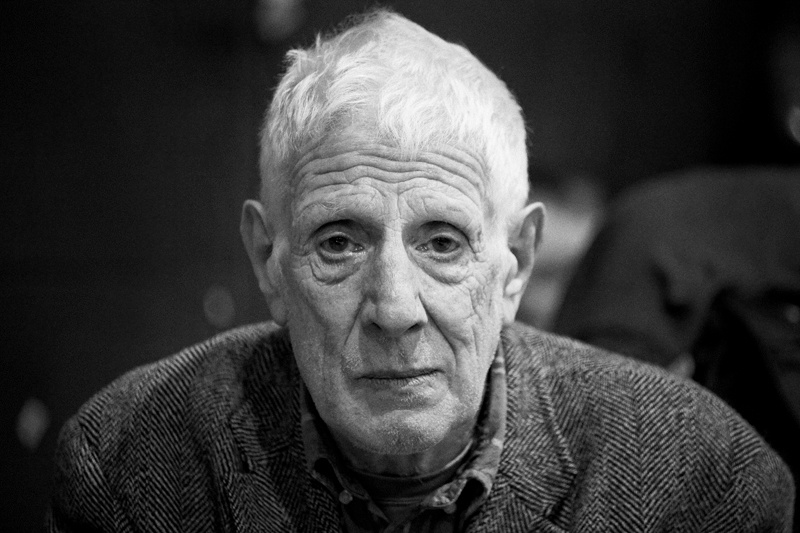

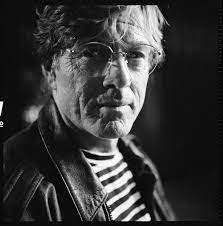

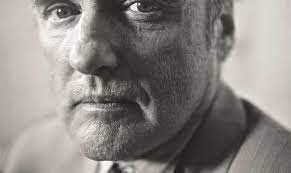

Christopher Jackson meets divorce lawyer Jeremy Levison, the co-founder of Levison Meltzer Pigott, and finds the art collector on top form

If I were starting out my legal career again, I’d be a divorce lawyer. But I wouldn’t be doing it specifically for the pay, or for the ringside seat on marital breakdown. I’d be doing it with a more specific intention: I’d be aiming to work in the offices of Levison Meltzer Pigott.

There again, I’d have a particular reason in mind, other than the quality of the firm. This, incidentally, is beyond question. Jeremy Levison and Simon Pigott (and later Alison Hayes) have been a regular fixture among lists of top family lawyers since founding the firm – their partner Clare Meltzer sadly died in 2003. Even so, I’d be going there for the art.

Many workplaces have fine art collections. One thinks particularly of Deutsche Bank (‘the art collection probably keeps the bank afloat for liquidity,’ says Levison), and I recall stumbling out of a meeting at UBS once to be standing in front of a sea of Lucian Freud sketches. But Levison’s collection is different.

For one thing it’s personal. It’s also part of a smaller business and so feels more special. So does he paint himself? “At school, I had no artistic ability whatsoever,” Levison tells me. “A couple of years ago, I went on a two-day oil painting class in Sussex. I absolutely loved it. However, the experience convinced me not to give up the day job.”

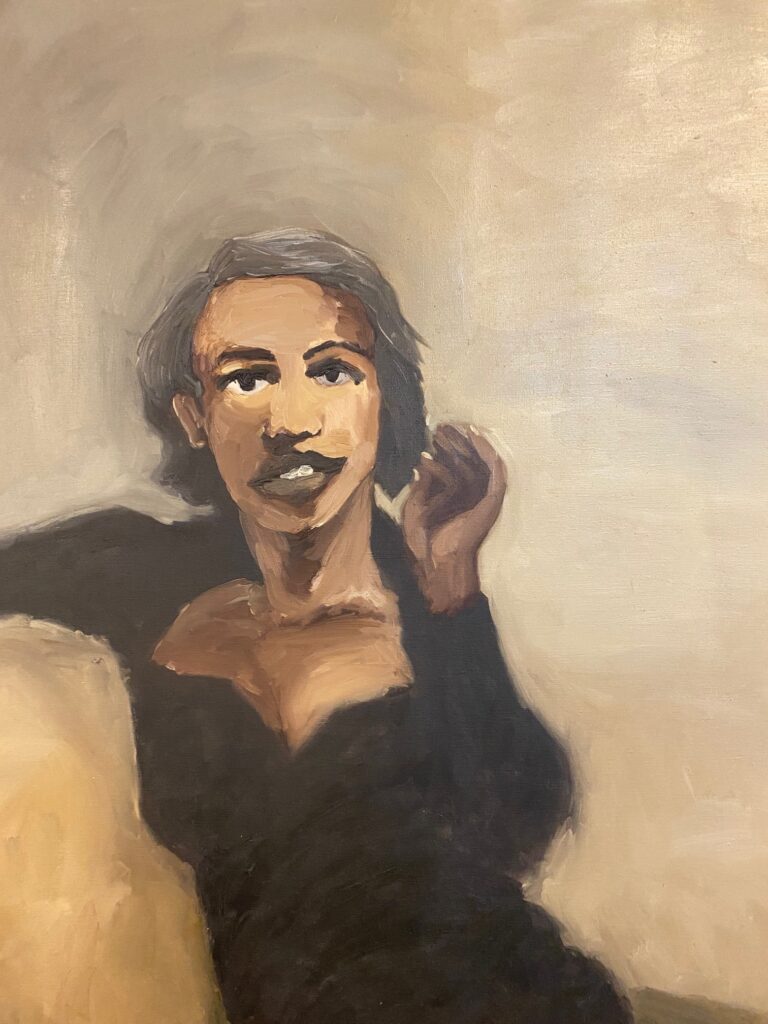

So when did he first start collecting? “It started in the 1970s. I met a chap who was doing prints; he had created a print and I liked it so I bought it. The next major purchase was in 1979. I had a broken heart at the time and there was this beautiful painting of a woman by an artist called ‘Molinari’ in a very ordinary shop window in Rome. That day my worldly wealth was 32 pounds, and this cost me 29 pounds then. I couldn’t resist it, and I still love the work to this day.”

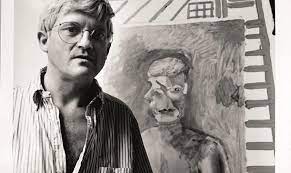

Over time, art collecting became an aspect of travel. His full success as a solicitor was in the future, and at that time he couldn’t have begun to realise how his collection – which now stands at around 500 pieces – would expand. “Whenever I went away anywhere I would buy a piece of art as the souvenir from that trip,” he recalls. “It just sort of went on from there. I was very fortunate, in that I became friends with someone who came into the office from off the street. He wanted to change his name from Christopher Holloway to Christopher Bledowski. He was not able to pay me, but he gave me a drawing. He was very influential in introducing me to various artists and the infinite creativity of the art world.”

Bledowski is an intriguing figure in his own right and deserves more attention. Bledowski would kill himself in Switzerland some time later, and Levison maintains that the quality of the work, which he has come to appreciate ever more over the years, might well have led to world fame.

But Levison’s art collection is a legacy of sorts for Bledowski. In time, Levison joined the firm Collyer Bristow and his art collecting continued. “We had all these bare walls,” Levison recalls, “and we had lots of artistic clients. I thought to myself, “Well, why don’t we give the clients an art exhibition on our walls. We did and it was great fun.”’

The idea of a more formal art gallery at Collyer Bristow was born. This was based on a belief that there is far more talent in existence than the art market – always caught up in the almost random anointing of the ‘next big thing’ – has time to recognise. In fact, Levison regrets the notion of the art market, preferring to talk instead about the art world. “The art world has morphed into the art market,” he explains. “I have a lot of time for the art world, but I don’t worry about the art market.”

It’s this essentially generous estimate of the talents of those who aren’t famous – or in some cases, aren’t famous yet – which informs Levison’s approach to buying art. “I love living with art, so it’s never worried me if a piece becomes valuable or not. If it does, that’s an added bonus, but if it doesn’t, it doesn’t matter in the slightest because of the joy of living with it.”

There is always generosity at work in Levison’s collecting. “At Collyer Bristow, I thought, ‘Well, we’ve got an acre of wall space here, and within 100 miles of London you’ve got probably 5,000 artists of real talent. Let’s do something to put them together.” The resulting space was a great place to work, and it began to alter the lives of clients and employees. “From an initial sort of quixotic curiosity among the members of staff, suddenly they all became more involved and began to look forward to the various shows. For instance, we had this young secretary and she began to take an interest. There came a time when she found herself needing to make a choice between whether to go on holiday for two weeks in southern Spain or whether to buy this little sculpture. She chose the sculpture. That sculpture over the years will have given her so much more joy than those two weeks of Sangria-fuelled sunshine would have done.”

For Levison, art continues to be a no-brainer. “At some restaurants in London you can go out to dinner with four of you and it’ll easily cost you £1,000 and we all know how that ends up the next day. Or you can go to any number of artists, and buy any number of works for up to £1,000, and enjoy them forever.”

So has the pandemic altered his approach to collecting? “Well, the one thing I did do was to buy a much larger house in order to have more wall space. The problem with my collection is that as it’s grown so has my ability to display it, so I lend a lot of it out.”

I mention that my first stop in New York is always the Frick Collection, just as my first stop in Cambridge is always Kettle’s Yard. Would he ever consider a Levison Collection somewhere in the UK? “I mean my collection is very modest compared to those. But I own this building down in Bermondsey and I wonder whether at some point that might become a home for the collection. I think my collection is an example that quite a lot can be achieved by someone who doesn’t have a great deal of money.”

It certainly does. I recall my own training at Stevens and Bolton LLP in Guildford – a perfectly decent firm but notable mainly for its blank walls. To some trainees, especially if you’re not sure if you want to be a lawyer, life at a law firm can seem like the end of the world. I say I hope the staff realise how lucky they are. Levison replies: “I think they do. And the clients love it as well. It gets constantly talked about, and a lot of clients ask for tours around the gallery.” Levison also concedes that it can be ‘quite a useful PR exercise because we can do evenings where outside organisations come in, and I can talk about how the collection came about.”

And of course, when you’re getting divorced it must be something to see such a collection on the walls – to know, in effect, that there are other narratives beyond your own, especially if the divorce is contentious.

Levison laughs. “Yes, I think coming to see your divorce lawyer is ten times worse than going to the dentist. It’s the moment when you’re admitting that your marriage is definitely over. I often think of myself as being, to a certain extent, a doctor. Some just can’t think about anything other than their predicament. But for others, the art collection is a relief – it’s something else to talk about.”

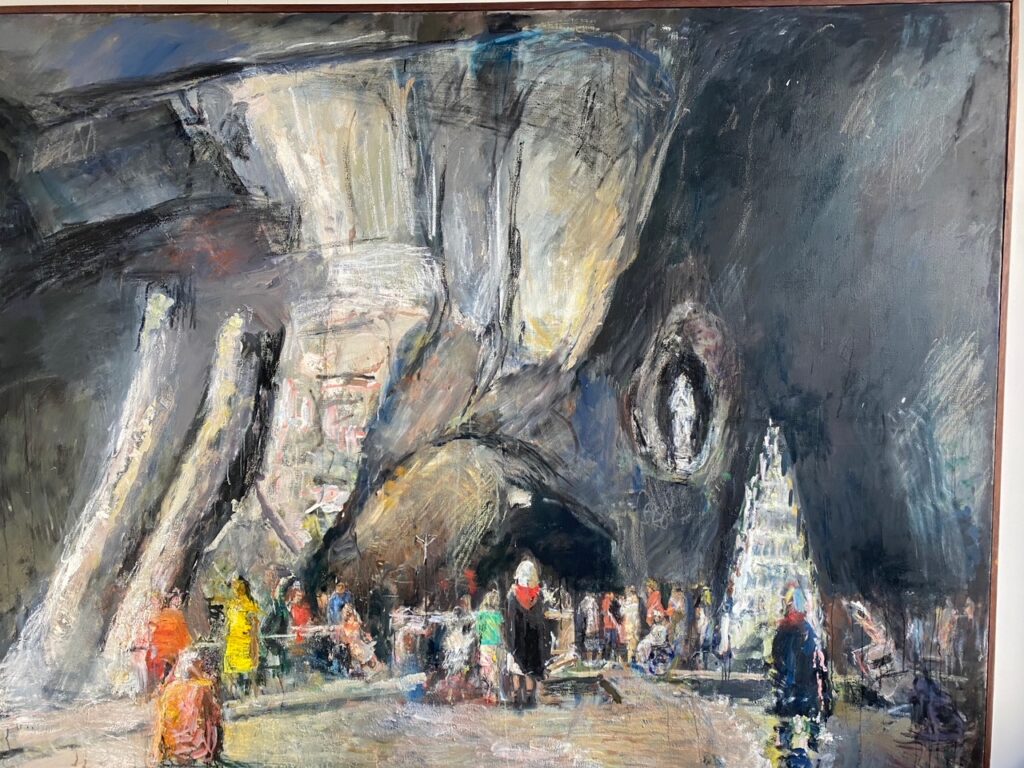

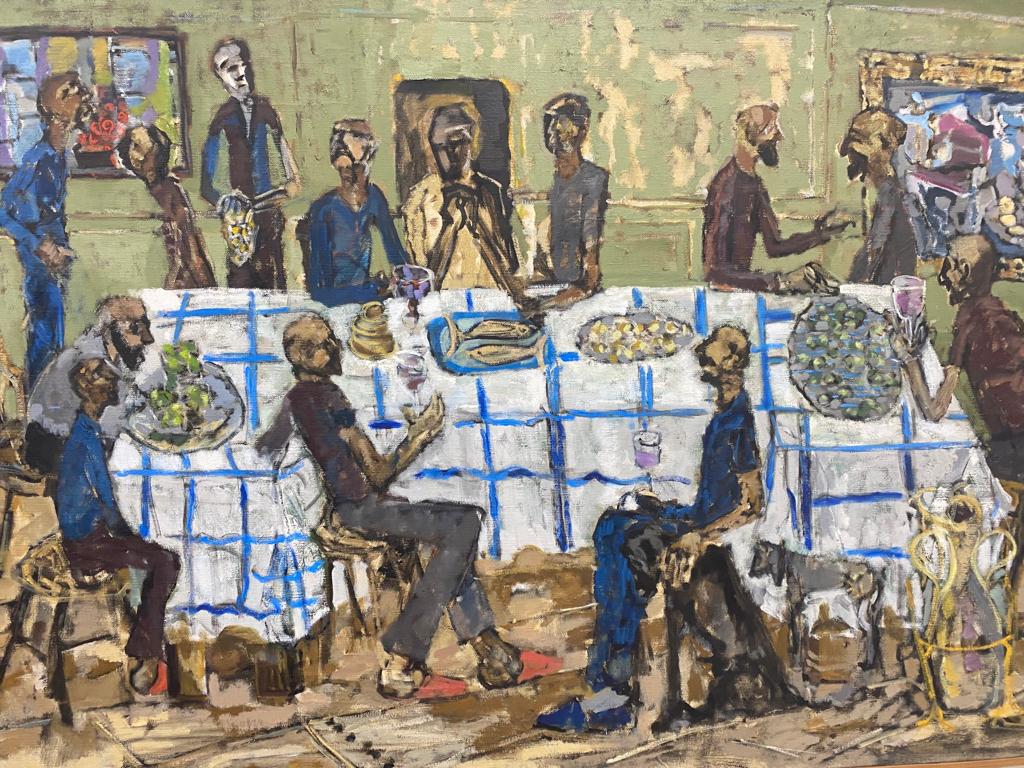

I’ve done the tour many times with Jeremy, but I am always ready to do it again. I happen to know that some of the best works – the Rose Wylies, a Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and a truly wonderful Ollie Epp are now at his new house. But the disappointment of that can easily be met by the fact that what’s here is still remarkable. There’s an Andrew Marr over a photocopier (“I’m not sure how good he really is, but I like it”), a wonderful picture by Anthony Eyton called “Our Lady’s Grotto at Lourdes”, a superb Still Life by John Bratby, various Eileen Coopers, a host of Stanley Spencer drawings, a Last Supper by Conrad Romyn and many, many others.

With the possible exception of Spencer, Bratby and Cooper, who feature in most surveys of 21st century art, all the artists here deserve more recognition – but each has also met with a superb champion in Levison. As always I return out into the street, not exactly regretting my decision to leave the law, but thinking that things might have turned out differently had I had the good luck to train at Levison Meltzer Pigott.