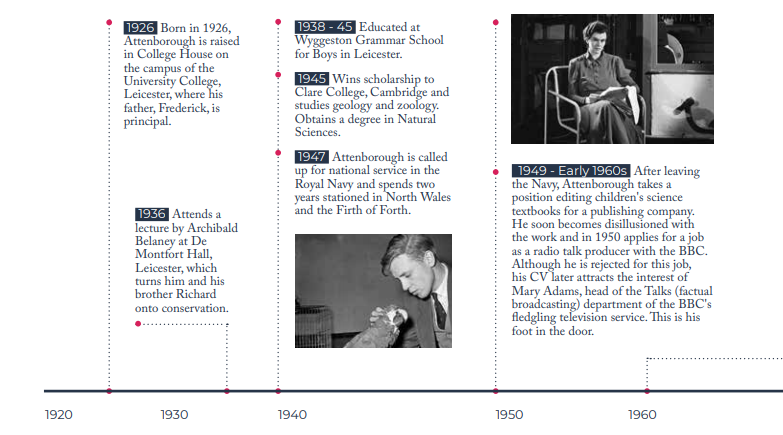

This week Sir David Attenborough’s new series Asia airs. We look back at Robert Golding’s exclusive interview with the great man at the start of the pandemic

‘This is a man who answers his phone,’ a mutual friend has told me, and Sir David Attenborough doesn’t disappoint. He picks up after just one ring.

The voice at the other end of the phone is the one you know. But it’s gravellier and without quite that voiceover theatricality it carries on Blue Planet. Those are performances; this is real life.

This is Attenborough on down time, conserving energy for the next program. His work schedule might seem unexpected at his great age. But Attenborough, 94, exhibits more energy in his nineties than many of us do in our forties. ‘I’ve been in lockdown, and it does mean I’ve been a bit behind on things. But I keep myself busy.’

To interview Attenborough is to come pre-armed with a range of pre-conceived images. Part-benevolent sage, part-prophet of doom, is this not the unimpeachable grandfather of the nation? Perhaps only Nelson Mandela towards the end of his life had comparable standing within his own country.

In 2016, when the Natural Environment Research Council ran a competition to name a research vessel, a very British fiasco ensued whereby the unfunny name Boaty McBoatFace topped the poll. This was plainly unacceptable, and so in time the competition reverted, with an almost wearisome inevitability, to the RRS David Attenborough.

Which is to say they played it safe and chose the most popular person in the country. One therefore has some trepidation in saying that these assumptions don’t survive an encounter with the man. It is not that he is rude or unpleasant; it’s just that he’s not as one might have expected.

‘Yes, this is David. What would you like to ask me?

Perfectly Busy

Though he has agreed to talk to us, the tone is adversarial. But there are strong mitigating circumstances to this. This is a man who is aware of his mortality: our conversation has a not-a-moment-to-lose briskness to it. He could also be forgiven for sounding somewhat tired. He can also be especially forgiven for having long since grown weary of his National Treasuredom. Throughout our call, he will refer to the claims on his time, of which I am one of many. ‘I get around 40 to 50 requests a day,’ he explains, adding that he seeks to hand-write a response to each. ‘I have been shielding during lockdown and am just coming out of that.’

But there’s another reason he’s busy: habit. The stratospherically successful enjoy a pre-established momentum, and continue to achieve just by keeping up with their commitments. So what has he been up to? ‘I decided to take this as a moment to write a book on ecological matters and I continue to make television programs,’ he says, referring to A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement, but not in such a way that makes you think he wishes to elaborate on either. He refers to a ‘stressful deadline’ and when I ask for more information about the book, he shuts it down: ‘Just ecological matters.’ There is a hush down the phone where one might have hoped for elaboration.

Nevertheless, Perfect Planet, one of his upcoming programs, is being filmed in his Richmond garden, and it has been reported that he is recording the show’s voiceovers from a room he made soundproof by taping a duvet to the walls.

Generation Game

In his courteous but clipped tone, he asks about Finito World and I explain that it goes out to 100,000 students. ‘I am often heartened when I meet the younger generation,’ he volunteers. ‘Their attitude to the climate crisis is very responsible.’

This is the paradox of Attenborough: a man of considerable years who has found himself aligned with the young. He’s that rare thing: an elderly revolutionary.

Perhaps we underestimate the sheer importance of his presence within the landscape. He is the benevolent sage who its bad form to disagree with, and he’s single-handedly made it harder for anyone in power to pitch the climate change question as a quixotic obsession of the young.

But he’s a revolutionary only in the face of drastic necessity, and refuses to be drawn on the question of our sometimes underwhelming political class. ‘I wouldn’t necessarily say that: we actually have some very good politicians.’ He declines to mention who these might be – but it suggests that Attenborough doesn’t want to ruffle unnecessary feathers.

Instead, he wants progress.

Transparent Medium

‘The thing about David is he prefers animals to humans,’ says another person who has worked with Attenborough for years. I ask him if the coronavirus situation will accelerate change. Again, he is careful: ‘I don’t know about that. On the one hand, I can see that our skies are emptier now and that’s very welcome. I suppose the extent to which the aviation sector will return will depend on the price points the airlines come up with.’

I suspect that some of his reluctance to be drawn into detailed discussion is that he doesn’t wish to claim undue expertise on areas outside his competence. There’s an admirable discipline at work, alongside a refusal to please

Bewilderingly honored – Attenborough has a BAFTA fellowship, a knighthood, a Descartes Prize, among many others – he has learned that the only proper response to fame is self-discipline. At his level of celebrity – up there with prime ministers

and presidents but with a greater dose of the public’s love than is usually accorded to either – he is continually invited for comment, and has learned when to demur.

‘I am sometimes asked about the well-known people I’ve come across in this life – the presidents and the royalty.

I’ve been lucky enough to meet,’ he says. ‘I say, “Look, if you saw my documentary with Barack Obama then you know him as well as I do.” Television is very intimate like that. My job is to create transparency.’

So instead of what one half-hopes for – backstage anecdotes at the White House or Buckingham Palace – one returns time and again to the climate crisis. This is the prism through which everything is seen, and our failure to follow his example, he says, shall ultimately be to our shame.

He will not be drawn into negative comment on Boris Johnson or Donald Trump. Instead, he says: ‘Overall, I’m optimistic. All I can say is we have to encourage our political leaders to do something urgently about the climate situation. We have to all work hard to do something about this.’

The Fruits of Longevity

For Attenborough everything has been boiled down to raw essentials. And yet his career exhibits flexibility. His success must be attributed to open-mindedness about a young medium which others might have thought it beneath them. It would be too much to call him a visionary. But he was in the vanguard of those who saw TV’s possibilities.

Fascinated by wildlife as a child, he rose to become controller at BBC Two and director of programming at the BBC in the 1960s and 70s. ‘Television didn’t exist when I was a young man, and I have spent my life in a medium I couldn’t have imagined. It has been a wonderful experience,’ he says.

The very successful glimpse the shape of the world to come, seize that possibility and enlarge it into something definite, which they then appropriate and live by. What advice does he have for the young starting out? ‘My working life has taken place in television. I don’t know how we will see that change over the coming years as a result of what’s happened. Communication has proliferated into so many forms. It is very difficult to get the single mass audience, which I had something to do with creating, thirty or forty years ago.’

There is an element of well-deserved pride about this. Attenborough’s original commissions at BBC2 were wide-ranging. The included everything from Match of the Day to Call My Bluff and Monty Python’s Flying Circus. One can almost convince oneself that he was a BBC man first and an ecologist second. ‘The world has become very divided in a way,’ he continues. ‘We prepare for a world when we’re young that’s gone by the time we arrive in it. To that I say, ‘It depends what your life expectancy is!’

But all along it was nature that thrilled and animated him. Attenborough is one of those high achievers who compound success with longevity. His is a voice that speaks to us out of superior experience – he has seen more of the planet than any of us. He speaks with a rare authority at the very edge of doom – his own personal decline, as well as the planet’s.

Urgent Warnings

He says: ‘Whatever young people choose to do with their life they must remember that they’re a part of life on this planet and we have a responsibility to those who will come after us to take care of it.’

I ask him what we should be doing to amend our lives and again he offers a simple thought: ‘We’ve all got to look to our consciences. Inevitably, some will do more than others.’

He sounds at such times very close to washing his hands of the human race. But then everyone in their nineties is inevitably about to do just that.

What Attenborough has achieved seems so considerable that one wishes to ask him how he has managed it. ‘I am sometimes asked about how I manage to do so much, but I don’t particularly think of it like that. I just reply to the requests that come my way: you can accomplish a lot by just doing one thing after the other.’

Again, the simplicity of the answer has a certain bare poetry to it: Attenborough is reminding us that life is as simple as we want to make it. Interviewing him at this stage in his life is like reading a novel by Muriel Spark: no adjectives, no frills, just the plain truth.

In his curtness is a lesson: there is no time for him now for delay, but then nor should there be for us. We must do our bit – and not tomorrow, now.

He is interested in Finito World and very supportive of our new endeavor: ‘This is a time when the circulations of magazines and newspapers appear to be falling. A lot of newspapers are aware of the climate emergency and the way in which we disseminate ideas has diversified.’

A thought occurs to me that stems from my lockdown time with my son, where we have been in our gardens like never before. Should gardening take its place on the national curriculum? ‘It’s obviously very important,’ he says, although he also adds – as he does frequently during our conversation – that he knows little about the topic. (Opposite, we have looked into the matter for him.)

Hello, Goodbye

I will not forget this interview with a man whose voice will always be with us. Part of Attenborough’s power is that he continues to warn us in spite of ourselves. He deems us sufficiently worthwhile to continually renew his energy on our behalf.

I mention that we watch his program with our four-year-old in preference to the usual cartoons on Netflix when possible.

At that point, perhaps due to the mention of my young son, he sounds warm: ‘Thank you very much, sir. It does mean a lot when people say that.’

It’s a mantra in journalism not to meet your heroes. Attenborough in extreme old age is brisk and sometimes even monosyllabic. This in itself tells you something: the world is full of the canonized but in reality saints are rare. Conversely, I have met those whose reputations were fairly low, but who turned out to be generous beyond expectation. We should never be disappointed when the world isn’t as we’d expected. It is an aspect of the richness of experience to meet continually with surprise.

But age will come to us all. If it finds me in half as fine fettle as David Attenborough I shall be lucky indeed. Furthermore, if it finds me on a habitable planet at all that shall also something I’ll owe in part to him. ‘Good luck,’ he says as he puts the phone down. This isn’t the man I had expected to meet. But I can persuade myself that he means it.

‘David prefers animals to humans’. Afterwards, it occurs to me that he saw me not so much as an individual, but a representative of that foolish ape: man. While Attenborough has been acquiring hundreds of millions of viewers, what he really wanted – and urgently required – was listeners.