By Christopher Jackson

To say it’s Vincent Van Gogh season in London might be to overstate the case: it always is. Every day people come from all over the world to see Sunflowers in the National Gallery – that great tour de force which reinvents the colour yellow for all time.

The artist’s fame would have seemed odd to his contemporaries, especially those who knew his eccentric habits in Arles, in southern France towards the end of his life. There was a time when Vincent Van Gogh couldn’t get anyone to look at his paintings. Today, it’s hard to get in front of one long enough to have a proper look without a tourist straying in to spoil the view.

But great fame is often reductive: in loving his pictures so much, we’ve tended to simplify him. We attribute his current reputation to ‘madness’ – as if Starry Night were primarily an expression of insanity. It’s true that Vincent struggled all his life with what we would probably label today ‘bipolar disorder’, but the truth is that Vincent was always sane when he was painting, and that painting was in fact his best method of staving off episodes which occurred throughout his life. These were frequent and he was heartbreakingly honest about them in letters to his brother Theo: “It appears that I grab dirt from the ground and eat it, although my memories of these bad moments are vague,” he once confided.

It is an arresting image: the great painter literally eating the earth. It might even serve as a metaphor of his achievement: Vincent was always imbibing real life, insisting on it to an unusual extent. His is a world of peasants and down-and-outs: he might be the only great painter in history whom it’s impossible to imagine as a courtier.

If you look at the popular image of the artist, you could almost imagine that Vincent is a completely separate case, someone we can’t expect to learn from at all, because we are not mad and he was. But his greatness cannot in the end be assigned to insanity, but instead to skill, vision and application. This means that we have more to learn from Vincent and his methods than we might think: this is true if we want to work creatively, but true also no matter what we wish to do with our working lives.

The first thing we mustn’t do is think him a uniquely hopeless case as a man in order to consider him a uniquely remarkable artist. As the pandemic has brought into focus, the world is always liberally stocked with mental ill-health. We might be deluding ourselves if we consider ourselves well, and Vincent not. It may even be that the reverse is the case more than we might realise or wish.

Secondly, we mustn’t forget how much hard work underpins Van Gogh’s achievement. The popular caricature of Vincent’s life still seems to invite us to imagine the world binary, divided between the sane and the insane. In actual fact, his life increasingly makes me think that we are instead divided between those who are committed and those who are not.

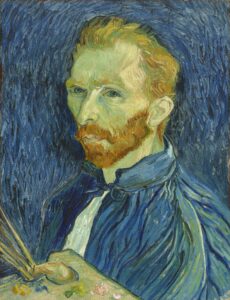

With all this in mind, I have come to the Courtauld Institute to see a remarkable exhibition housing 27 Vincent self-portraits collected together across two rooms. The Institute has spent a fortune renovating itself, and emerged on the other side of £57 million in expenditure looking almost identical to what it looked like before.

Anyone who wishes to get upset about this financially alarming decision however, can seek solace in being restored to one of the great collections of the world. Among them is Vincent’s famous Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear, which he made after the terrible and incomprehensible incident in Arles which most people know about: after experiencing increasing tension in his friendship with Paul Gauguin, he cut off his own ear and delivered it to a prostitute with a cryptic note attached.

The exhibition may be said to build towards this picture as towards a crisis. But there is another way of looking at it: here, spanning over a decade of helter-skelter work, is a celebration of the joy of discovery. We might be disinclined to cut off our own ear, but we should certainly leave open the possibility that there is an activity waiting for us in life which we can grow into over time: a room we might walk into without ceilings or impediments where we might become more and more richly ourselves. By that measure this exhibition is extraordinarily valuable: it shows the sheerness of Van Gogh’s application to the art of painting and might even unlock something within ourselves.

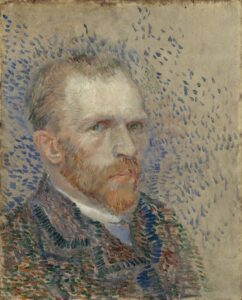

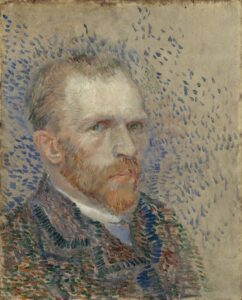

The early pictures, drawn in his native Holland, are sombre affairs compared to what he would later produce. As such, they are a very precise measure of how far he would develop. By the vigour and the colour they lack, these pictures imply both an openness to doing things in a different way and also state an uncompromising desire to make his craft secure before he did branch out. The dominant influence here is Rembrandt. Here again there is a lesson which might apply to other disciplines: seek the best in what you wish to do, learn from it respectfully, and only then stake out new territory.

There’s another lesson, stemming from the fact that so many self-portraits exist. Vincent was a little unnerving as company, partly due to his physical appearance which was by no means prepossessing, and partly because of his unpredictability. As a result, throughout his short life, he found it difficult to find models willing to sit for him. The only model always willing to do so was himself.

This points to his resourcefulness and to his determination. In his letters to Theo – some of the loveliest documents in the history of art – we get a lot of detail about materials Vincent is buying. Here again, he is always sensible with money, frugal with what he’s able to afford, and a fortunate beneficiary of his brother’s generosity. Unfortunately, because Theo’s letters weren’t kept, and Vincent’s were, we rarely get a sense of Theo’s view of Vincent, though what we do know points to fraternal adulation. But this absence further augments the sense of Vincent as a man alone.

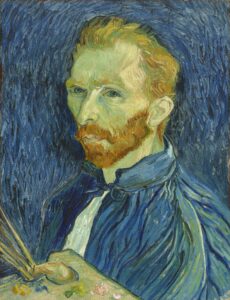

The Courtauld exhibition shows that Vincent always left himself free to experiment, without ever losing the intensity of work ethic which always marks out his pictures. He studied his own face from every angle. He told us his every mood. By the end of this exhibition, we feel we know him. It’s this intimacy – together with the perennial simplicity of his signature – which makes us comfortable (think Don Maclean’s song of the same name) enough just to call him ‘Vincent’. We do not call Cezanne ‘Paul’ or still less Monet ‘Claude’. Vincent is touching in a way few great artists are. One of his virtues was always humility. It’s this which has brought him so many posthumous champions. Knowing what it was to be despised, he never despised anyone. He is always in the trenches of life with us. It is difficult to think of another artist who cared so much for the downtrodden and the outcast.

In these self-portraits we see always the same determined mouth, the slightly watery eyes, the hooked and even austere nose, and the receding hairline. But this is where the similarities between each picture end. Given that the same subject recurs throughout, it is an exhibition so various in its mood and techniques as to cause astonishment.

The main reason for this versatility is that Van Gogh had made himself open to the gigantic discovery of the age, Impressionism, and then moved swiftly forward, making out of it a unique and wholly personal achievement.

But here again we must be careful. The truth is that in a pre-Internet age, Vincent never could have discovered Impressionism without having been immersed in the art world through Theo’s work as an art dealer. He couldn’t google Seurat; he had to meet Seurat.

In actual fact, if we might look at the matter objectively Vincent made all the right moves, which makes his achievement no accident at all. In fact, he often foresaw in his letters that his victory would have to be posthumous. There was a worldly, even calculating side to him at odds with the stock image of the freewheeling madman.

Other lessons can be found in his life. He moved away from a career in the priesthood to which he was unsuited, though he took what he had learned there – the importance of the numinous in life – and applied it to his art. Nothing was ever wasted. He then applied himself with rigorous dedication to painting, and connected himself in that world, making sure that he was working not according to some outdated understanding of his craft but to its latest developments.

As he carried out all this he was frugal, careful, and utterly committed. He also had an unfailing instinct for the next subject, and was prepared to subject himself to upheaval in order to pursue those instincts to their logical conclusion. The most famous example of this is his decision to leave Paris and move down to Arles in southern France.

He did so because he craved another light. It was a masterstroke – when what Vincent calls that ‘high yellow note’ has entered his pictures, we feel he has come home somehow. It looks like something which had to happen. But this again is an illusion: he made it happen. Again, because his life ended tragically, we forget that he was possessed of exceptional self-reliance to have got as far as he did.

Of course, a more organised person would have found somewhere less depressing than Arles to settle. It’s true that it had a few places going for it – the old Roman amphitheatre and some decent museums in towns nearby. But one senses that almost anyone else would have pressed on to Italy – or to Tahiti, as Gauguin did and follow their decision to relocate to its logical conclusion and find their way to a more appealing town.

It was his hyperactive fascination with what he saw which made him stay. The fields, the café, his chair, his room: these were enough for him, because he realised that just by going to Arles he had learned to see things in a way which nobody before him had been able to do.

No-one has seen like that since – and it must be that no artist has communicated to so many people with such immediacy. In fact, his work has the immediate comprehensibility of photographs: it is mass art in the way in which magazines are. And yet it stands up.

This is abundantly clear at the blockbuster Vincent Van Gogh: the Immersive Experience now touring the world where huge crowds, including children, experience Vincent ‘interactively’. At times the exhibition – as in its roomful of sunflowers – feels somewhat gimmicky, but sometimes it astonishes.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a vast, almost cubist cinematic experience, where we see the familiar story of Vincent’s life written in subtitles while music contemporary to Vincent’s life plays and his paintings are shown in detail on large screens. The fascination of the show is that it’s impossible to see all of it at one go, and we’re reminded of what a complicated thing a life is, and especially a creative life like Vincent’s.

But the principal reflection is this: it’s very hard to imagine a show on this scale for any other artist dead or alive. Picasso, perhaps. Hockney, just maybe. But in each case, I doubt that their work and life has the deep appeal of Vincent. Picasso is at heart too grotesque and misogynistic; Hockney’s work is probably not quite good enough, especially in the last 20 years or so.

What accounts for this? It is that Vincent truly loved the world and truly loved all people. In his life, he imagined creating an artists’ colony alongside Gauguin and others where the world would be righted. Sometimes, Vincent had little self-awareness: he had neither the organisational skills, nor the money, nor really the personal magnetism, to make such a thing happen.

But it happens today at any Vincent exhibition where people gather in a kind of loose arrangement of fascination, seeing the world again through his eyes. Of course that arrangement dissolves swifter than Vincent had in mind when he imagined a colony of artists. But it is something – more than something.

And with every passing year we need to understand that Vincent’s popularity isn’t a quirk of madness. It was because his life in its way was exemplary, and there is much we can learn from him.

Van Gogh. Self Portraits runs at the Courtauld Institute until 8th May 2022