Christopher Jackson looks at the question of whether we inhabit an age of consensus – and asks whether there’s anything we can do about it

Our cities are so far advanced down a misguided aesthetic that even revolutionary projects must be undertaken in bad architecture. Michaela Community School is located opposite Wembley Park tube station. Adjacent to a ring road, its surroundings feel like a testament to generations of bad urban planning linked to the demands of the car. Despite this you somehow suspect that Michaela Community is revolutionary before you’re even through the gates.

Even amid the squalor, banners proclaim central Michaela precepts: ‘Work Hard’, ‘Be Kind’, ‘Top of the Pyramid’. It also reminds you of its excellent results: “Ofsted rated Outstanding. Over 75% to Russell Group Universities including Oxbridge, LSE and Imperial.” These messages feel somehow incongruous when set alongside the mess we have made of this part of North London.

Inside the impression of difference sharpens: you know straightaway this isn’t a normal school. You are greeted by examples of the children’s excellent artwork, including portraits of David Cameron, Queen Elizabeth II and Boris Johnson. Newspaper clippings detail the visits of dignitaries and interviews with Michaela’s Headmistress Katharine Birbalsingh, Britain’s so-called ‘strictest headmistress’. Lauded by the right, and despised by the left, Birbalsingh has done a difficult, almost unprecedented, thing: she has acquired fame as a teacher.

As I am escorted up to see her, I am aware of a mood in her administrative team which doesn’t usually accompany my visits to schools. It is, in fact, the sort of awe which surrounds rock stars and Cabinet ministers. And yet the respect surrounding the headteacher has a distinctive strain often absent in those other cases: it is genuine love and respect.

In place of the usual din of schools – places which are usually full of vaguely located cries, as in a shopping centre – at Michaela there is only the hush of concentration. Famously, Birbalsingh has created a regime where there’s no talking in the corridors and students regularly submit to having their mobile phones put in storage to aid their learning.

As I walk on up to Birbalsingh’s office, I walk past a group of children moving between lessons. They remind me of contented nuns and monks shuffling through a cloisters. One looks up at me and offers a wry smile. In the context, it’s subversive – a moment of independence within a strict regime.

I will find I like the school a lot. What has been achieved here is beyond doubt. But I think afterwards about that boy with the smile. It feels emblematic of the independent streak.

Blair and his Heirs

Independent thought, it might be said, hasn’t had a particularly illustrious 25 years. It is now a quarter of a century since Tony Blair came to office and proclaimed a new dawn. You can look at Blair’s government in a number of ways. It might be considered a ratification of Thatcherism insofar as Labour altered Clause Four, making the party far friendlier to business. It can be remembered for its miserable foreign wars. It can also be seen as a period of devolution away from Westminster, with results which we’re seeing today in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

But in spite of the controversies, Blair’s electoral success was so great that, in ways we might not appreciate, we still live in the aftermath of that 1997 landslide, and his subsequent victories in 2001 and 2005.

That’s because large majorities are reflections of consensus. In 2010, David Cameron’s Coalition government adopted a strong dose of Blair’s Europhilia (with a few concessions to his backbenchers), and continued New Labourish policies when it came to the academisation of schools, international aid, civil partnerships, an interventionist foreign policy, and many other areas. The similarity between the two culminated in the spectacle of Blair and Cameron – alongside Blair’s predecessor John Major – campaigning together on the same losing side in the 2016 referendum. Furthermore, the three of them argued for the same Covid restrictions in March 2020.

This has left a gap into which some conservatives – including the likes of Peter Hitchens, Toby Young and Douglas Murray – have been arguing for things outside the Blairite consensus. For Hitchens, the Conservatives’ failure to promote a return to grammar schools is a particular point of criticism, as is the laxity of the police. For Young, lockdown was an outrage perpetrated against the great tradition of English freedom. For Murray, the Blair-Cameron axis is wrong over immigration, and was deservedly repudiated in 2016. All three of them would argue that there are far too many woke MPs, some of whom nominally belong to the Conservative Party, but who aren’t really conservatives at all.

Most heretically of all, each of these thinkers would reserve the right to subject the climate change orthodoxy to proper scrutiny, if only because questioning things is in the British political tradition, not to mention the broader scientific tradition. Whether we agree with all this or not, each of these writers reads today bracingly if you grew up under the Blair consensus: they read like people thinking for themselves.

Past the Age of Consent?

Consensus is, of course, not a bad thing per se. We have, for instance, been governed by a consensus that murder is a punishable crime for millennia to no-one’s disadvantage but murderers. Likewise, our shared consensus that Shakespeare is a great playwright has preserved Shakespeare, and is another example of what might be called profitable consensus. When Tolstoy cantankerously announced towards the end of his life that Shakespeare was no good, he was thinking independently, but not particularly well. There is a distinction then to be made between useful polemic which ultimately turns out to be true, and wilful contrarianism, which causes a lot of noise and misleads a lot of people.

But despite these reservations, it must be admitted that consensus sometimes feels flabby. When too many people have arrived at the same conclusions it might be that those conclusions are dated, or have lost some spark.

So which kind is the the Blairite consensus? There are some warning signs which stretch beyond Tony Blair’s own personal unpopularity. It certainly isn’t quite as popular as its holders would wish, or suppose. This fact was made clear to Remainer voters in the 2016 election: it turned out that a surprising number of people in the country were, while being ostensibly civilised, quietly thinking the unthinkable: that the Blairite worldview might be wrong somewhere at its Europhilic core.

But what really brought the question of independent thought into sharp focus was the Covid-19 pandemic. Whether lockdown might be deemed an overreaction or a wise necessity, it forced government into our lives like it has never been before and this in turn raised considerable questions around how we receive and sift data, what is true and what is false, and above all, what our personal relationship is with the notion of government interference.

It brought to the fore the whole question of statistical modelling and for some thinkers has ramifications not just for how we tackle the spread of viral disease, but also for the broader way in which we use scientific data. “The models were completely wrong,” the economist Roger Bootle, another independent thinker of the right, tells me. “And it’s the same in relation to the climate models – although not to quite the same extent, because the most unpredictable thing about the Covid-19 models was human behaviour, and that has slightly less bearing on the climate change models.”

But the fact remains: by 2022, a generation of professionals in senior positions had come to maturity thinking and feeling roughly the same things about most things. If their worldview is wrong at all, then remarkably few ramifications have come their way: on the contrary, they have usually found their sense of consensus ratified by professional success. Lockdown caused the consensus-bearers no harm since, financially, little can. Lawyers and accountants remained for the most part in spacious housing doing jobs which it is possible, and in many cases enjoyable, to do from home. Doctors were designated key workers and spared the strains of home schooling.

Even so, there are some warning signs that what the consensus bearers have been thinking and feeling might be wrong after all. If we look at inflation or high energy prices, the dubious tactics of Extinction Rebellion, the increasing extremism of wokeism, the long waiting times on the NHS, the former Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s tax rises to pay for lockdown, and the relatively settled landscape post-Brexit, there is a sense that there might be value in listening to voices, from both left and right, that lie outside the consensus. We might not change our minds on policy but we’ll certainly learn something about how to think.

The question is not just: “Who is right on these issues?” It is also: “What does independent thought look like in this day and age? And who has a motivation to practice it?”

An Audience with Katharine the Great

To promote independent thinking, what kind of education system do we need?

For the right, Birbalsingh has arrived as a kind of saviour in this realm, seeming to embody some better method. Of course, as the writer of Ecclesiastes understood, there is nothing new under the sun: her new way of doing things is tethered to the old. Put simply, Birbalsingh argues for the importance of promoting knowledge of a shared cultural tradition in order to foster the independence of thought which might ultimately free us of what she views as the groupthink of wokeness.

When I sit down with Birbalsingh at Michaela Community, I tell her that the place reminds me of grammar schools. She doesn’t find it a helpful comparison. “There are a couple of grammar schools round here,” she admits. “But they take the top slice. Any good teacher knows that it’s really complex when teaching the bottom sets. If you’ve only got the top students, you don’t have to think about learning in the same way. When you have a great cognitive diversity you have to do more.”

In this sentence, ‘more’ means strictness and standards. I wonder aloud whether there’s any danger about the regime, and whether it might over time create conformity instead of individual inspiration? I tell the story of my old English teacher at Charterhouse, Philip Balkwill, who was famous for his eccentricity. In one English lesson, he came in, played Beethoven’s 9th symphony and then left the room without explanation.

Birbalsingh is amused, but not especially impressed: “The thing is, you can only do that kind of thing when you’ve got a selective intake. If you do that in an inner-city school, the kids will all just be laughing and jumping around and running out of the lesson. And then you say, “Well, what have you achieved?” You’ve just created chaos. The kids have just lost all respect for you and you will find it very difficult to build up your resilience again.”

Here then is one obstacle to independent thought: it can’t be something you do overnight. You’ve got to lay the groundwork with discipline first. I mention that Balkwill’s lessons for me operated on a kind of time bomb. I came to realise years later that he was talking about the porousness between disciplines and how music and literature might be interconnected.

Birbalsingh laughs: “The fact that you only realised that ten years later: that’s ridiculous. Teaching is about making things explicit. He was doing things like that for himself and so that he could say to himself: “I’m the most amazing teacher.” He liked being eccentric. In the end, how much did he really teach?”

I say that it felt like being bequeathed a certain permission to roam freely across intellectual disciplines. Birbalsingh doesn’t think that approach will generally work: “You need to realise that the kids here have no idea who Beethoven is unless we teach them that. Once I gave an assembly about Beethoven’s Fifth, as I wanted them to at least recognise the tune which you hear all the time. I was talking about how it was difficult for them growing up in a time of grime and drill.

The worst for me when I was growing up was Kylie Minogue and how everyone was scandalised by her shorts. I put a picture of Beethoven up on the slides. Later when I was having lunch with the kids, I realised they thought Kylie Minogue and Beethoven were contemporaries because I hadn’t made it clear. They don’t know that there’s music from the 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th century and how it’s changed. When they learn music here we start with A, B, C, D.”

She continues: “What you mightn’t realise is just how impoverished some children are and that’s what an inner city school is. Those antics of your teacher you described are not helpful.” I think again of the boy smiling in the corridor. I agree with Birbalsingh, and yet some small part of me wants to retain the idea of another approach. I find that Mr Balkwill’s lessons can’t be so instantly jettisoned. Something would be lost.

Uncle Toby

Sometimes of course having a good education culminating in all the expected excellent results might not be a spur towards independent thinking: in fact, it might lead you up too obvious a career ladder meaning precisely the opposite – that you never have to think for yourself at all. It used to be that a dose of failure did a little good.

I talk to that noted independent thinker Toby Young – so much a bugbear of the left, that he seems to exist in a permanent ferment of being cancelled and recovering from his latest bout of cancellation. He tells me about his somewhat chequered early education: “I initially failed all my O Levels, and went to two different comprehensives. I retook and got three Cs, which was enough to scrape into the sixth form of William Ellis. I did well enough to apply to Oxford. I didn’t meet the conditional offer, but was sent an acceptance letter by mistake. When that was pointed out to me, they then offered me a place – it was an unconventional route.”

Young, who would go on to set up The Modern Review, The Spectator Online and, in 2020, The Daily Sceptic, credits the entrepreneurial side to his upbringing. “My father was one of the people behind the Open University. He created over 50 organisations of one kind or another during his life. A couple of those got torched in David Cameron’s Bonfire of the Quangoes. He was a lifelong socialist and one of this country’s first sociologists in addition to running a Research Institute in Bethnal Green, he implemented these institutions. That gave me confidence.”

Young was then exposed to the left-of-centre culture of Oxford, before relocating to America, and landing among the uber-left campus life at Harvard. This was the era when Alan Bloom published his famous Closing of the American Mind, a sort of prophetic cri de coeur about the encroachment of what we would now call ‘wokeness’ onto campuses.

Young recalls: “Within my year group at Brasenose [at Oxford] studying PPE, we had the full gamut from a Monday Club tubthumper to a member of the revolutionary Communist party and every shade in between – and there were only ten students.” And in the US? “At Harvard, there was nothing like that range of opinion even in the entire government department, which encompassed hundreds of students. The main debate was between two types of liberalisms – Nozickian and Rawlsian liberalism – that was the extent of the disagreement, and Nozickians were a real minority!”

This sounds like the sort of landscape which Katharine Birbalsingh, in her different way, is committed to pushing back at. Young agrees: “I’m a big fan of Michaela – it’s incredible. In Michael Gove’s wildest dreams I don’t think he’d’ve anticipated the free schools programme would have given birth to such a perfect embodiment of what he views a school to be.”

So is the encroachment on independent thinking less to do with some sort of Blairite inheritance, and more to do with groupthink migrating from America to this country? Young replies: “I certainly think that as British universities have admitted more American students and grown in size, they have attracted left-wing academics with a sense of social mission who want to change the world by converting and evangelising. But it’s partly a generational shift; most of these people were radicalised in the 1960s. You gradually see more of a left-wing imbalance in the professoriat.”

This mindset in turn has infiltrated, or so the argument goes, every strata of society, achieving numerous coups: it captured most of the major cultural institutions; the BBC; and even large swathes of the Conservative Party. In response to the professional calamity which can sometimes assail those who speak up against this consensus, Young founded the Free Speech Union in 2020.

I ask Young about the future of independent thought and he initially strikes a surprisingly optimistic note: “The curious thing is that even though all our main cultural institutions – the BBC, heritage institutions, performance arts companies, the National Theatre – they’ve all been captured by this rather small-minded illiberal ideological cult, at the same time you’ve had right-of-centre figures winning elections. The professions and the educated elite are beholden to this woke cult, but it hasn’t filtered down to ordinary people.”

This, in Young’s view, is a sign that most people still retain the habit of thinking independently. “There’s a disconnect,” he explains. “You see that in the way in which the trans lobby has got into trouble by trying to give trans women access to women’s changing rooms in department stores without trying to persuade the public it’s the right thing to do. That’s proved quite unpopular and authoritarian. All is not lost.”

Even so, he also issues a note of caution. “One of the reasons to be doubtful about how quickly the spirit of liberty can be restored is that it was revealed to be in a very decrepit state during the last two years. It was surprisingly easy for the government and various public health agencies, civil servants and the BBC to persuade people to exchange their liberty for safety and much more so than it would have been in the Asian flu in the 1950s. That was true not just of Britain but of most liberal democracies.”

Of course, we must be careful here not to attribute all independent thought to lockdown sceptics. For instance, the vaccines – not to mention the inventive way in which those vaccines were rolled out – arguably constitute a greater example of initiative than anything shown by those who stood from the touchlines arguing against lockdown.

But Young, Murray and Hitchens aren’t arguing against science. What they would say is that science has become dangerously allied to politics, that it is poorly reported leading to a bogus consensus (usually in the direction of the exaggeration of danger), and that an atmosphere of intolerance has grown up around some of the conclusions it has arrived at. Clinchingly, they would simply defend their right to ask questions about it.

A Question of Method

So how would Young go about teaching independent thought? “I’ve been wondering whether, under the guise of teaching schoolchildren how to debate, you could teach them some critical thinking skills,” he replies. “It’s extraordinary when you argue with young people how often they fall back on what they think of as the trump card of their own lived experience. It doesn’t matter if you present them with data that contradicts their claim.”

I ask for examples. “Let’s say you’re arguing with a young black student about whether or not Britain is an institutionally racist country,” Young says. “You could point out, for example, that more black boys go to university from underprivileged backgrounds than do white boys. Or you could cite the fact that Indians on average earn more than white Britons.

You could also point to the success of boys of African heritage at university and in the professions. There’s actually all sorts of evidence that not being born with a white skin isn’t an insurmountable handicap in this country. You could present that case as reasonably and calmly as possible but they could just say: “That’s not my experience, but you’re a white man and from my point of view, that’s bollocks.” Nearly all children nowadays fall back on this Megan Markle ‘my truth’ trump card.”

So what do we do? Young has clearly been thinking deeply about this: “It would be really helpful to teach children why that isn’t a knock-down argument, and why it isn’t a trump card. It’s also important for them to know why data is more important than anecdote and how you can merge lots of different people’s lived experience to come up with a more objective balanced view as to what the collective experience is.”

Does he think the teaching profession will be able to do this? Young isn’t sure. “Teachers these days are shy of challenging emotional impassioned teenagers – particularly if they’re members of disadvantaged groups. In taking that stance, they allow these irrational ideas to flourish.”

So would that require some kind of shift in the curriculum? “The main thing we need to do is to teach them the rudiments of how to build an argument, recognise a good from a bad argument, and teach what the most common logical fallacies are. Those analytical skills would mean you’d develop a bullshit detector.”

Avenging Angel

It’s interesting that Young’s background is predominantly entrepreneurial and I begin to wonder whether I’m really talking to a journalist or to an entrepreneur. Is there something about being an entrepreneur which fosters independent thought? To find out, I talk with James Badgett, the CEO and founder of the enormously successful Angel Investment Network. Badgett, 40, isn’t just a well-known entrepreneur in his own right, but, given the unique nature of his business, also the centrepoint of a vast amount of economic activity.

So does he feel that as an entrepreneur he’s under greater pressure to think independently? “It’s quite straightforward. When I wake in the morning, first I have to check I’m okay. Then I have to make sure my team is okay. You can’t lie to yourself as a business-owner because you’ll get found out. That means that if the government tells you to work from home, or if The Guardian tells you leaving the European Union is a disaster, or if Greta Thunberg tells you the planet is about to burn – you have a responsibility to go away and check if those things are actually going to happen.”

Badgett is known for holding unpopular opinions, but he views it as important for his many businesses to make sure he holds firm. “I think I’ve got to the point now where almost any view I hold isn’t held by the majority,” Badgett says. “I’ve grown used to people thinking I have an unusual take but I’m not going to stop saying what I think.”

Badgett’s success can partly be attributed to an ability to cut through the range of information he receives in order to decide on the right strategy for his businesses. He tells me of his dislike of corporate settings: “You just feel yourself become cretinised when you sit in these big firms.

You ask for the coffee, and sit back and feel somehow flattered to be in there – and I think that happens to a lot of people who become quite limited in their outlook. They’ve first become too comfortable. But I’ve learned that in business you’ve got to be careful not to fall for all that. You have to remain rooted – and you have to surround yourself with the right people.”

He is sceptical of anyone too who “suggests strategies which are easier to say than to do” and is always creative in the way he runs his companies. Badgett has a Nepalese office of the Angel Investment Network, and realised before the pandemic that it would be affordable for the company to have a top chef cook for his workforce and that it would also be a great boost for the company. “I went ahead and did it – though I expect the BBC would have told me it was impossible.”

Like Young, Badgett opposed lockdown in March 2020, and also counts himself a climate change sceptic. “One thing I disagree with in relation to Greta Thunberg is this elevation of the child to the level of sage. She’s still very young and her predictions are likely to be wildly inaccurate just as Dr Niall Ferguson’s were during Covid-19.”

I ask Badgett whether he thinks we need to do more in education to teach commercial acumen. “The truth is that most people walk into working life absolutely financially illiterate and what you’re seeing today is the effect of a woke university system on the workplace,” he replies. “Basically, people don’t have the skills by which to sift information or to judge what’s true and what’s false – what is theory, and what is fact. What I think does happen though is that people who run businesses become more attuned to that – again, if you don’t your business will go under.”

Whether one agrees with Badgett or not, he is a reminder that the ability to think independently as a society must be tied to a greater commercial sense.

Approaching the Source

If independent thought is under threat then there are a number of clear possible reasons for it. One is the influence of American wokeism on our university system as outlined by Young. Another might be the impact of the Blair-Cameron axis. A lack of commercial acumen is another: some have noted that epidemiologists were more likely to make gloomy predictions about coronavirus since, being in the pay of the government, they didn’t have to live with the commercial ramifications of those predications.

But most people accept that the media, and the way in which we receive our information, also impacts our ability to make up our own minds effectively on important issues.

One person well-placed to consider these matters is Sir Bill Wiggin MP, who represents North Herefordshire. He has spent 20 years in Parliament, and has had a front row seat on the way in which reality can be distorted by the media – and how this causes both misery for beleaguered MPs and confusion in the electorate who are often unable to find their way to primary source material.

After years in the public eye, Wiggin says he’s become acutely aware of what journalism is and how it should be read. “When you read the newspaper, you’ve got to be careful,” he explains. “I’ll read whatever’s lying next to me – but I don’t read it believing it to be the gospel. I’m happy to read The Sun, The Guardian or The China Daily but I’m always reading it in a certain way with the awareness that they will have an agenda.”

And what, in Wiggin’s opinion, is their agenda? “It’s quite simple really, it’s trying to outrage you or to terrify you.” So what would Wiggin’s advice be to people in respect of reading the mainstream media? “Don’t base your life on a publication: be broader than that. You need to be. And also realise that this sensationalism is driving all aspects of the media. For example, I get The Daily Express online. It has wonderful headlines: “Brexit delivers huge increases in British business.” Two days later it will say: “Brexit cuts British business”. They’re playing us! We’ve got to stop thinking that journalism is a Christian and pure-spirited thing. It’s as commercial as Star Wars.”

I mention to Wiggin that I value the way in which my history degree gave me a habit of going to the primary source in order to assess the events of the past.

Wiggin agrees but worries that these skills are being lost in the contemporary media maelstrom: “Today, The Guardian and the BBC are going to the source for you. When you watch the news tonight, you will see Vladimir Zelensky make an announcement about how Russians are losing in Ukraine, and the newsreader will say: “Now, we go to our Ukraine correspondent.” I want to hear from Zelensky not your correspondent! Then you might cut to another correspondent or expert: it was second hand when you got it from the BBC – now it’s third hand.”

The Mp also points out that we tend to practice critical thinking better in other areas of our lives: “Anyone reading this article will know that if they go to a football match, what they see is different to what they read about it afterwards: but they don’t apply those lessons to their politics. Soak it up but don’t close your mind. When you read that x is wicked or that y is good a little voice in your head should say: “Well, that’s what it says here”. You shouldn’t be prepared to die in a ditch according to what you’ve read.”

Good Humours

One notable thing is that some right wing thinkers often seem to injure their case with a certain cantankerousness which somehow makes their case less persuasive. Of course, there might be mitigating circumstances. Most of them haven’t been listened to throughout their professional lives, and must feel a sense of mounting frustration at always feeling in the right and then watching governments continually make catastrophic moves.

Although Peter Hitchens can be funny, it is probably the case that there has rarely been a less Christian-sounding Christian in the public sphere . There can sometimes be a sense of infinite probity about his public persona which feels somewhat tiring – reading him sometimes, one feels that nobody could manage long in his ideal state. One would want to be free a moment, like that boy in the Michaela Community corridor. There is a frequent note of exasperation – a sense of being almost tired of being so in the right – which makes one want to lodge objections, and which has probably led to his ideas being infrequently taken up by government.

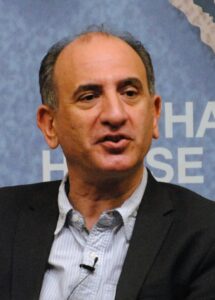

This brings me to Armando Iannucci and the importance of comedy in the realm of independent thinking. John Cleese recently observed that there is no such thing as a ‘woke joke’, but it seems to me that there are still vestiges on the left which are able to raise that profound laugh which lets you know an independent truth has been arrived at.

Iannucci has always been able to do this – most notably in The Thick of It and Veep – those superb comedies which could only have been written by a unique cast of mind. Sure enough, Iannucci has been in fine form during the pandemic having penned an epic poetic satire on the first years of the Johnson administration called Pandemonium. We need only read its opening page to know that this is a voice of the left which is hardly caught up in groupthink:

Tell, Mighty Wit, how the highest in forethought and,

That tremendous plus, The Science,

Saw off our panic and Globed vexation

Until a drape of calmness furled around the earth

And beckoned a new and greater normal into each life

For which we give plenty gratitude and pay

Willingly for the vict’ry triumph

Merited by these wisest gods.

It is worth noting how the big laugh comes from the line ‘that tremendous plus, the Science’ – the same Science which is in its way is poked at, and queried, by Young, Hitchens, Badgett and others. Here it is being mocked too. Blairism itself was full of those ‘tremendous pluses’, whose validity we were never meant to query.

Pandemonium mocks Johnson, Matt Hancock, Tory donors, and Dominic Cummings. It suggests again that this era of consensus needn’t necessarily be worried at in a misanthropic spirit. It might be done with wit and laughter too. It is an enduring fact that many of the great thinkers of the 1930s – one thinks of George Bernard Shaw and Ezra Pound – fell for Stalinism and Nazism respectively. It took Charlie Chaplin and PG Wodehouse to laugh them out of town.

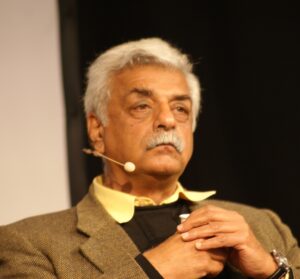

Iannucci doesn’t extend his mockery to the Labour Party in the poem – and perhaps it would have been a better poem if he had. Bu one leftist intellectual who is prepared to query Starmerism – currently a kind of low energy Blairism – is the philosopher and poet Tariq Ali. Ali has just published – to the right’s dismay – a book attacking the legacy of Winston Churchill called Winston Churchill: His Crimes, His Times.

For Ali, the habit of consensus thinking began further back in time during the post-War period: “I would refine the analysis slightly,” he says, when I describe the theory of the Blairite consensus. “The post-War consensus which was more or less agreed by Labour and the Tories after the Second World War, was that we have to go down the social democratic route. In Britain, this consensus was implemented and never altered in any meaningful sense, until it was broken definitively by Margaret Thatcher.”

For Ali this is all bound up in the Churchill cult which began at that time, and has been continued by Johnson. Interestingly, Ali says that he prefers reading thinkers like Peter Hitchens to those on the centre right. “Obviously Peter and I won’t agree on most things but I have some respect for him. There is a degree of honesty and integrity in Peter which I don’t find in liberal writers. Look at the stand he’s taken on Julian Assange. I am amazed he’s still a columnist on The Mail on Sunday: it’s much sharper than things I read in The Guardian.”

It’s this which often marks out independent thinking: integrity and the desire to conduct our thinking for the right reasons. And what does Peter Hitchens say in return? “I think Tariq Ali is a valuable independent voice because I think freedom dies without dissent. He’s undeniably intelligent, and undeniably thoughtful. I disagree with him profoundly on many things, and have done so publicly on such matters as the nature of Fidel Castro’s Cuba.”

And what has it been like when they have sparred? “He has responded courteously, as a civilised person should, though he should have a higher opinion of The Mail on Sunday, which has a strong record of independent thinking. I think we both come from an era when an opponent was not necessarily an enemy. I also suspect him of having a sense of humour. I wouldn’t say this feeling has anything to do with my own Marxist past. Most of my former comrades dislike me personally, though I can’t be bothered to return the compliment.”

So perhaps the surest route to independent thinking is an education like that offered by Birbalsingh at Michaela Community, but with just that hint of a smile offered by that boy in the corridor, and by Philip Balkwill back at Charterhouse in the 1990s.

But we also need much more: better commercial education as suggested by the examples of Toby Young and James Badgett; a deeper awareness of the need to go to the primary source as espoused by Wiggin. We also need Tariq Ali’s perspective of the deeper past.

But it is Armando Iannucci’s ability with a joke which can sometimes seem most pertinent. It is this which verifies where we really stand on an issue, and which clears the decks and allows us to think clearly about problems.

I didn’t tell Birbalsingh about another one of Philip Balkwill’s lessons. He would show us Beyond the Fringe and the great sketch where Peter Cook plays Arthur Streeb-Greebling who has spent his life ‘underwater teaching ravens to fly’. It was the silliest thing I’d ever heard – and it made me want to watch more. ‘Is it difficult to get ravens to fly underwater?’ asks Dudley Moore. “I think here difficult is a very good word,” Cook replies.

The same is true in the realm of independent thinking – but as the problems of the world mount, and the implications of groupthink become clearer, this is increasingly a conversation we need to have as a society.