By Robert Golding

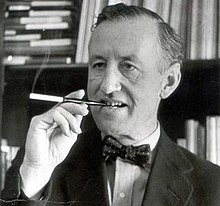

I’m lucky to possess an attractive vintage edition of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963). Whenever I take it down from the shelf, as I do now, it reminds me that more people should read Ian Fleming. The writer may be best known now for the multimedia phenomenon he has given the world, but he began as a good prose stylist. For instance, this book, the twelfth Bond novel Fleming wrote, begins with a description of a seaside sunset: ‘Then the orange ball would hiss down into the sea and the beach would, for a while, be entirely deserted, until, under cover of darkness, the prowling lovers would come to writhe briefly, grittily in the dark corners.”

This isn’t writing of the first rank. Anyone who’s ever watched a sunset knows that the setting sun doesn’t hiss at all and I don’t think lovers prowl the beach so much as loiter – but if we’re seeing all this through the eyes of Bond, then perhaps they do. In Bond, women are always an aspect of struggle. His weakness for them is the thing most likely to get him killed.

Any discussion of Bond and the question of work must always come back to that crucial fact, also punchily described in the opening pages of OHMSS: ‘Today he was a grown-up, a man with years of dirty, dangerous memories – a spy.’

Empire Broccoli

But before we get to life at MI6 in No Time To Die, it’s worth noting that each time a Bond film comes out, it’s a reminder that we exist just after the greatest shift in human experience since the advent of Guttenberg’s Bible – namely, the move away from print towards the moving image.

It might be that Bond encapsulates this change more vividly than any other character. That’s partly because of the sheer enormity of the franchise. It’s also because someone whom the previous generation got to know through language in Fleming’s books, is now someone we’re acquainted with predominantly as spectacle. Even so, the books remain reasonably near.

And, of course, there are still the books for those who want them. They reliably take up three quarters of a shelf in each outlet of Waterstone’s. But the sheer number of people who see these films is a reminder of their addictive, joyous quality.

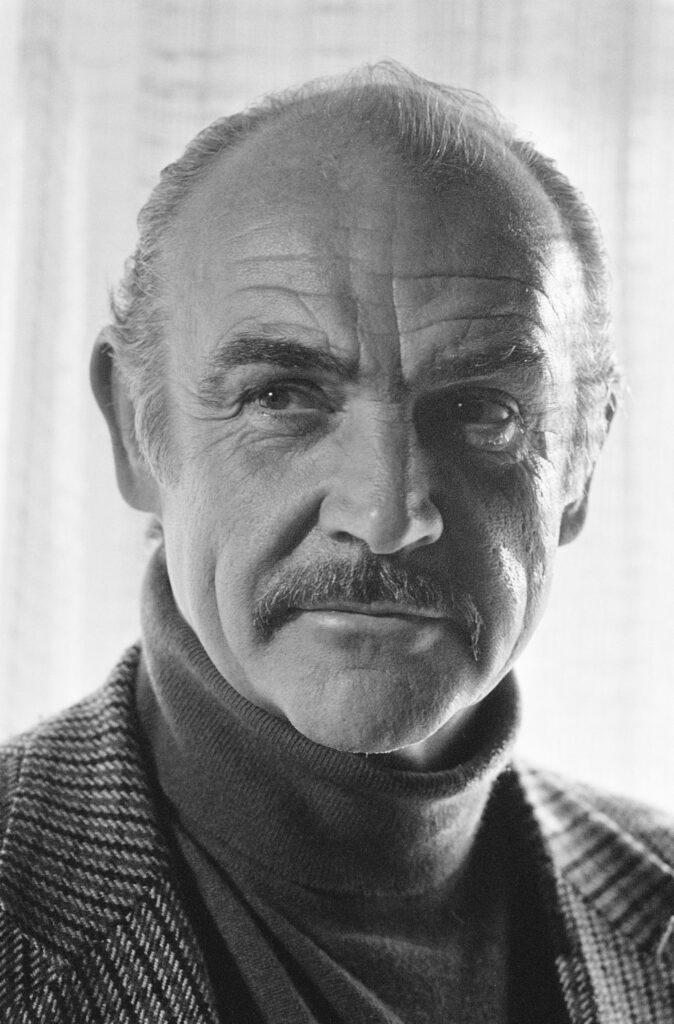

Our collective need of Bond on the big screen stretches all the way back to Sean Connery’s debut in Dr No (1962). No Time to Die is the 25th instalment. During that time, the film industry has grown exponentially: this state of affairs is best illustrated by the credits at the end, which denote a bewildering array of jobs in the sector from casting directors, to stunt men, makeup artists, production crew, runners, textile technicians and others. While a film of this scale is being made, it exists as something between a camping site and a corporation.

The figures continues to impress. In 2019, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport estimated that there were 289,000 jobs in the UK film, television, radio and photography sector.

From the Pandemic with Panic

No Time to Die arrives at a time when all these jobs are in flux, and the industry in peril. This is a situation which, one suspects, only James Bond can remove. As punters, we are separated for the most part from the stress of the impact of the pandemic on the film world.

But we do glimpse it occasionally. Earlier this year, audio was leaked of an apoplectic Tom Cruise on the set of the latest Mission Impossible 7 haranguing crew for failing to take proper Covid safety precautions.

If you heard Cruise’s stressed pep-talk, you’ll know that the industry has never needed a good Bond film quite like it needs it now. But the world is in a similar predicament. One thing Covid-19 appears to have wrested from us is a sense of harmless fun. In spite of every attempt to reach for gravitas, Bond cannot help but remain that.

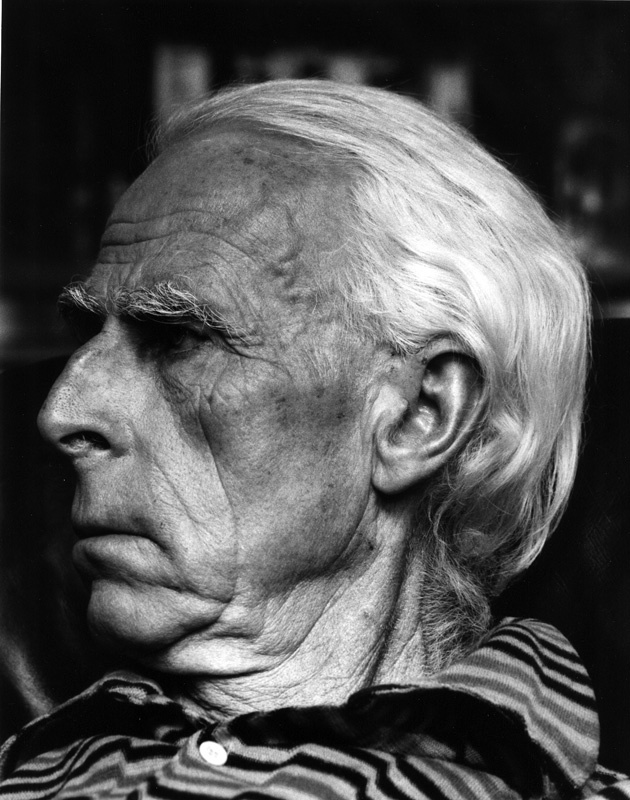

Even so, a desire for seriousness is what has defined the Craig films. This needs to be placed in context. The gritty – and for some unbeatable – performances of Sean Connery kicked off the series. His tenure began with Dr. No and took us through From Russia with Love (1963) – for many purists, the best of them all – Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965) and You Only Live Twice (1967). There then ensued a brief hiatus where George Lazenby, in an underrated film, took over in the filmed version of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), before handing back to Connery for that notable dud Diamonds Are Forever (1971).

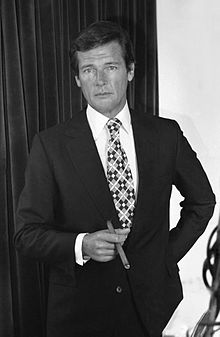

Golden Moore

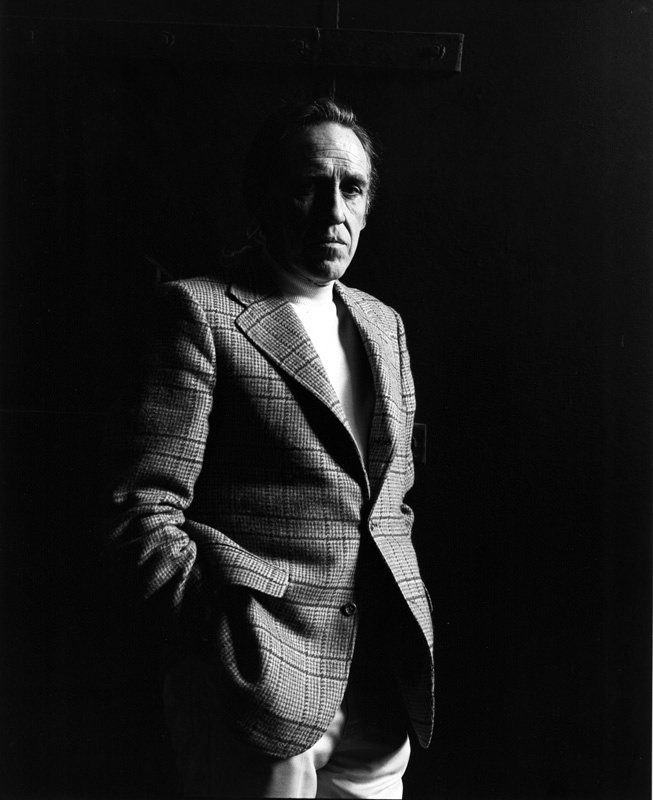

The advent of Roger Moore changed everything. Moore’s spirited and amusing performances moved the films far from the books, and seemed to bust forever the notion that Bond was a character of any psychological depth. These films, beginning with Live and Let Die (1973), and ending with A View To A Kill (1985), where Moore looks almost elderly as he puffs his way up the Eiffel Tower in pursuit of Grace Jones, are great fun, though not untainted by a casual imperialism and misogyny which wouldn’t pass muster today. Even so, few Bond fans would want to be without them. They are of their time – but more than that, they were undertaken with the understanding that Fleming’s world is predominantly fairytale.

The Moore films have been subject to push back, in some degree or other, by all the actors who have played Bond since. Timothy Dalton, better known as a stage actor, sought inspiration from the Fleming books in License to Kill (1987) and The Living Daylights (1989). Piers Brosnan channelled Moore to some extent, but there were some attempts – especially in the casting of Judi Dench as M – to bring the series up to date. Those films declined precipitously in quality following the credible first showing Goldeneye in 1995.

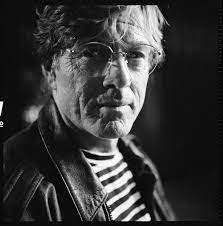

And so to Daniel Craig, where the seriousness has been amped up throughout, and everything possible done to give Craig the opportunity to explore what it really means to be a spy – and especially a 00 with a famous licence to kill.

Low Morale

Underpinning all the Bond films is the unavoidable fact that our hero is a serial murderer. During the early films, we are permitted to consider him a hero because he is always protecting the free world from the diabolical schemes of Ernst Stavro Blofeld. The more diabolical the scheme, the more comfortable we are with the notion of him as a hero, since we can turn a blind eye to what he is capable of.

Geopolitically, we need to feel that Britain is in some sense ‘good’ for these films to work – otherwise the murder is all for nothing, and we can’t quite cheer on the hero.

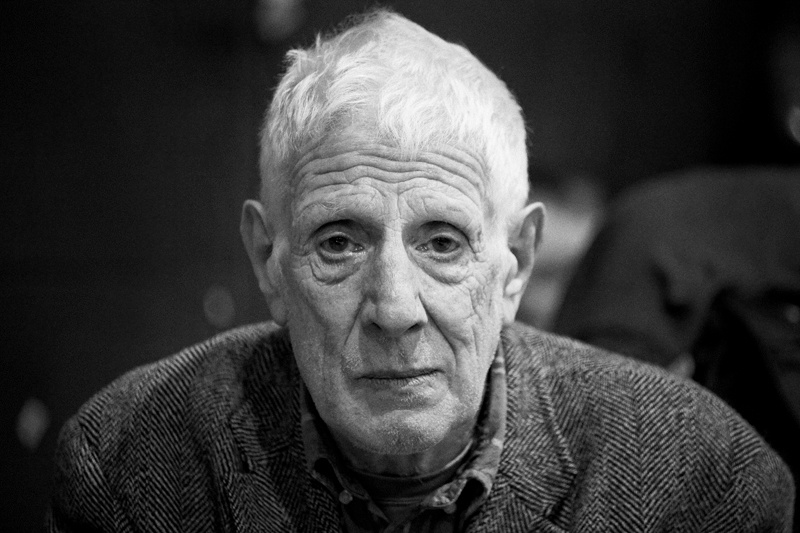

The unseen factor on all these films is the parallel success of the books of John Le Carré. For their style alone, Le Carré’s books will go down as some of the finest of the post-War period. Those books work by intrigue, and make particular use of the device of the double agent. This in turn creates a strange world where the excitement is not knowing who to trust – and whether all the sacrifice is worth anything.

For Le Carré, the British Empire was an object of suspicion. These suspicions had their climax in Brexit, and we now know that the novelist died an Irishman. It’s difficult to imagine Fleming as anything other than British.

It could be argued that Bond was never supposed to be Le Carré-esque. Fleming’s stories work on the implicit assumption that democracy is a more desirable thing than communism – and that there is such a thing as good and evil, and right and wrong.

One also wonders whether the biggest mistake was to try to apply Bond to the world which grew up after the fall of the Soviet Union. The decision to do so can seem as absurd as placing the Three Musketeers in a battle against the Taleban in Afghanistan.

At any rate, during the Brosnan-Craig years, something like the Le Carré worldview was appropriated and smuggled into the Bond movies, where it didn’t belong. It was Lord Alfred Tennyson who wrote of the ‘long unlovely street’ referring to almost any street in London – and the Daniel Craig Bond movies show a London just as drizzly and depressing. It is a city hardly worth fighting for. It’s Le Carré’s London – a city to make you want to get an Irish passport.

Faulty Leiter

In No Time to Die, the role of the spy has shifted still further. Craig’s cold eyes are uniquely able to convince us that he kills for a living – but we are not always sure if we should be supporting him. In No Time To Die, Bond himself seems to be afflicted by a peculiar kind of self-loathing – and, as throughout Craig’s tenure, is continually retiring from espionage. It has been said that the power of the name ‘Bond’ has to do with his being in some way wedded to Queen and country. Here that central bond has loosened.

One of the perennial images of Craig’s time in the role – and it arises again in No Time to Die – is of Bond, who must be on slender government provision, retired from active service in five star luxury, somewhere in the Caribbean or the Pacific. He is always questioning the validity of his own job – the series isn’t a particularly good advert for recruitment into MI6, and very misleading as to pension expectations.

A further complexity is the US-UK relationship which, we are told in this film, has strongly declined. The friendship between Felix Leiter and Bond, which wheels about throughout the franchise, is here not wholly believable. In License to Kill, Bond is very close to Leiter and driven to revenge by the villain’s murder of his wife. But by Casino Royale (2006), Bond is only just being introduced to Leiter at the casino after experiencing a defeat by Le Chiffre at poker. Yet by No Time To Die, the pair has somehow reverted to a sort of nostalgic friendship which doesn’t feel to have been quite earned by the intervening films.

The Leiter-Bond relationship is always a yardstick for describing the nature of the US-UK ‘special relationship’. In Casino Royale, when Leiter offers to stand Bond at poker, the moment expresses the benevolent view of America which formed during the Obama administration. In No Time to Die, Bond observes that operational coordination between the two countries has become all too sporadic: “That’s not good,” Bond says grimly.

If we’re being strict about it, this is probably wrong historically, since during the Trump administration, when this film was made, the former president made repeated promises of an imminent trade deal with the UK: cooperation was actually somewhat better than it has subsequently been under President Biden. But the point is that whatever political observation is being made – and it’s not particularly clear – the moment doesn’t work as drama.

Artistic Freefall

This sort of thing wouldn’t matter if the film didn’t continually present itself as high art. This makes one want to nit-pick. The fact is that slips and inconsistencies have beset Craig’s time as Bond, all marked by a slightly cavalier approach to the way the world actually works. There often appear to be logistical difficulties in the villain’s enterprises which are skimmed over. I have sometimes – though I realise I’m not supposed to – wondered about the property ownership situation of the farmhouse at the end of Skyfall (2012). Out of nowhere, Bond reappropriates his childhood home in order to lure Javier Bardem’s villain to it. Inevitably, it is destroyed, and Bond assisted in its defence by Albert Finney, who seems to be a sort of steward of the manor – but who owns it now?

If the film is to end with a meaningful death scene with an actor as good as Judi Dench doing the dying, then this must all be put in context, as it always is in Shakespeare. We are entitled to wonder whose house she’s dying in.

Even so, the films do show the way in which the world – and the workplace – has changed. Diversity and inclusion is now represented by Naomi Harris as Moneypenney and – in No Time to Die – by Lashana Lynch as having taken over Bond’s number 007. The presence of women generally in powerful positions had been addressed by Dench’s six appearances as M, and it is now thought acceptable to revert to Ralph Fiennes. Perhaps this in itself might be a truthful indicator of the sometimes slow progress of equality in the workplace. Whether we like it or not, many CEO positions are still filled by men who resemble Fiennes, and many secretarial roles by women: there’s still a long way to go, and it’s good that the Bond films reflect this.

Meanwhile, a more modern attitude to sexuality is shown by the casting of the tremendous Ben Whishaw as Q, who in this film is shown preparing for a date, and the identity of the date referred to as a ‘him’.

The film contains some references which feel prescient – the central plot, as is also the case in other Bond films, involves the development and possible global dissemination of a deadly toxin which can kill millions. This brings in human touch as an aspect of the plot, and the word ‘quarantine’ features – this has a weight now in our lives which it can’t have had when this film was being made.

But in general this movie entails people being back in a room together. We see crowded bars, and no social distancing – almost as if the whole pandemic had never happened – which is, of course, precisely what we want to feel as Bond returns to our screens.

And so Bond continues to reflect the times, even though there was never any real need for him to do so. Bond was always a creature of the Cold War, and my sense is that this alone is what makes the Connery films superior: they’ve kept Fleming’s context. That might yet turn out well for the franchise. As Vladimir Putin ramps up his attack on the world’s gasoline prices and democracies, Bond may soon be relevant all over again, and sooner than we think.