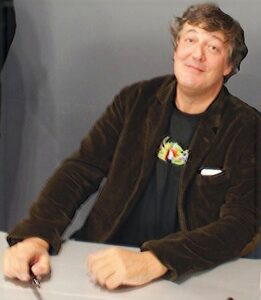

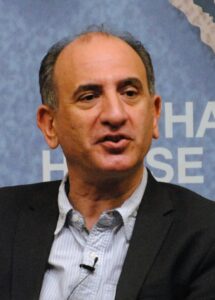

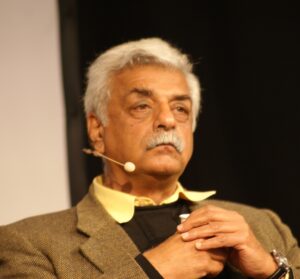

In a special Finito World interview, the 2024 Masterchef champion Brin Pirathapan and Fortnum & Mason CEO Tom Athron are brought together on the third floor at the famous Piccadilly store

The real joy of networking isn’t to meet people for oneself: it’s introducing people to one another. When the opportunity came up to interview Brin Pirathapan, the brilliant Tamil Sri Lankan winner of 2024’s MasterChef, we put heads together at Finito, with help from Janine Stow at The Quorum Network, to decide what to do about it.

The answer came in a flash of inspiration: Fortnum & Mason is being altered by its brilliant CEO Tom Athron, and the third floor, formerly the menswear floor, is now set up for food experiences. There is a gin bar, and a cooking area where the store hosts masterclasses, as well as the beautiful Fortnum & Mason culinary products.

Once we’d decided that might be a good idea, we thought we’d go one further and interview Brin and Tom together and see whether anything came of it.

Brin is there as I arrive, looking resplendent in the sort of outfit which Federer used to wear at Wimbledon in his pomp. So I ask Brin if it was always food for him? “I have always loved food. I almost took it for granted because my parents always cooked so well. The table was always full of delicious Tamil Sri Lankan food.”

Perhaps unknowingly a standard had been set. “When I went to university,” Pirathapan continues, “there wasn’t really a conscious decision that I was going to learn to cook: it was just a thing that happened. I wasn’t willing to eat the same bland meal plan every day. But I didn’t have the funding or the finances to be going out for food all the time or to be buying the most expensive ingredients. That situation created the chef that I am today.”

Let’s be clear what this wasn’t: it wasn’t a decision not to have that Deliveroo. It was more financially constrained than that. “I never had to refuse to lazy route. I would cook instead of having a takeaway just because I had to: it was either that or cook boring meals. I never leant towards takeaways. I thought: ‘I can probably do it as nice or nicer myself and learn a new skill’.”

At that time, Brin can have had no way of knowing where it would lead. “Really, I like to eat!” he says simply. “I like nice food and I wanted to do it myself. It was essentially self-reliance and learning a skill. I started cooking for friends, when they came over for dinner. And they’d compliment me. I’d want to do more because it was nice when people said I’d done a good job.”

It seems as though we all need to find that thing in life where we feel there’s no particular ceiling: that we can continue to develop across the whole course of a life. “Something about food makes me want to learn more and more about it. You’d watch people on television or online and the chef has these intricate skills. And I wanted to know how to do that: I was so invested in it. So it probably comes back to just it being a pure passion that I wanted to be good at.”

But even here – he didn’t know how far it would take him; but he had found his passion. “I’d been a veterinary surgeon for a good few years, and I didn’t necessarily think food was ever going to give me a new career. But I think I knew that if I didn’t give MasterChef a go, I would never be able to make it a reality.”

It’s as if you find a thread in life – and it’s not that you’re pulling it, but it pulls on you and leads you on. “It seemed a bit unsafe. I’d been planning on working in veterinary. When you do that, at least by the age of 15 you’re already committing time; you’re committing your holidays to work experience you’re committing your evenings to studying. It’s quite hard when you are within those walls of a structured education and a structured career to dream outside, because it seems really unsafe. And let’s be honest, the food industry isn’t exactly the safest industry to be in. It’s tough – but MasterChef has given me the platform now.”

Brin has long been a fan of MasterChef so it was a huge thing to apply for the show. “I’ve watched it since I was a young age, and it’s made me the chef I am today. When I started the show, I was so worried about being knocked out in the first round. But my fiancé was very firm – she’d seen me moaning about my normal job.”

I say I find it hard to imagine being able to focus on cooking when the cameras are rolling. “It would have been impossible to play to the camera,” he says.

“Every dish I created I pushed myself to the absolute max – so timings were incredibly tight. Obviously within each cook, you need to have an interview with the judges too – other than that, there was no room for error, and I got used to the cameras being there. I needn’t to know there was no time left over for each cook – that there was physically and mentally nothing more that I could have done.”

Reminding myself of the formidable MasterChef judges John Torode and Gregg Wallace, I ask whether their verdict ever affected his concentration. “It’s hard – especially at the start. When they come round, all you’re thinking is: “Do they think I’m doing this wrong?” You start questioning yourself. But as you get to know them, they’re actually very good at calming you down and making sure you’re relaxed.”

I find it hard to imagine Torode or Wallace in calming mode. What stays with Brin is the long silence when the judges give their verdict. “From the first cook to the last, that silence when they are eating, to when they say their first words – that will haunt me. It was an eternity, and it never got easier.” It all came down to the last cook, and I think the way in which Brin approached the most important moment of his life speaks volumes about his character.

“I’d felt so proud to have just gotten to the final and I felt that no matter what, I now had a platform to make a new career in something I love. I wanted to show the judges what my journey in that competition had been – and what the competition had given me. So within every course, you could see multiple elements that reflected a certain dish or a certain opportunity we were given, or a restaurant we went into.”

It is that humility, combined with a willingness to learn which seems to mark out Brin: these traits, when they are combined, place no limits on a person’s potential development. There is throughout our conversation a sheer fascination with cooking – the timings, the sourcing, the service – everything. When we come onto Brin’s famous octopus dish, he is fascinating about the complexities of making the dish work.

“It’s a difficult meat to cook actually. It’s really easy to make an octopus tough and you want a good couple of hours, but in the MasterChef kitchen you only have an hour and a half. So, then you also add in the difficulty of cooking it within a pressure cooker, which can change its texture – and the thing about that is that it’s blind – you can’t see what’s going on inside.” I could listen for hours to anybody talking with passion about the detail of what makes them love it.

Brin continues: “Five extra minutes in a pressure cooker is probably the equivalent of a half an hour of standard cooking. So there’s a lot of margin for error and the texture is one of the main aspects in an octopus. It’s a little bit like a scallop. It’s really easy to get that texture wrong.” You can see why someone who can talk like this will have a long and exciting career: because they’re interested in the task itself, independent of any reward it may bring.

As Brin went through the competition, he kept his head down, until he found himself caught up in that iconic moment when the winner is about to be announced. “Throughout the entire process, I didn’t allow myself to look too far ahead. When I look back, I think one of the reasons [KL6] I did well was because I didn’t give myself the pressure of dreaming about winning. I was simply thinking of the need to execute everything to the best of my ability. So when they did call my name, it was more of a shock than I can ever imagine.”

And, of course, in that moment – even longer in reality than it looks on television, according to Brin – he was crossing over from one world into another, one of considerable opportunity.

Surveying the landscape of options now, Brin is characteristically level-headed and sensible: “I don’t think you have to win MasterChef and open a restaurant immediately. The food industry in 2024 is so much broader than what it was probably 20 years ago, which is so exciting for me because I think in my life I need variety anyway, to keep interested.

Private dining and supper clubs are really interesting to me. They’re the areas where I can show off and kind of going back to when my friends used to come to dinner. I’ve loved all the services that I’ve done throughout the show and any private dining I’ve done afterwards. So I want private dining to be a decent portion of what I do, and I’d also love to write a book.”

There is a sense then in which Brin is going full circle – or rather, moving forwards without forgetting where he came from. “The reason I want to write a book is because, going back to how I started cooking, you can cook amazing food without having to stretch your budget. And it can be very cost-effective. We’re at a time now where people are struggling, because ingredients are so expensive.

I want to bring that through in a book but also, I want to give that to people online because that’s how I learned. I would see these incredible chefs doing amazing dishes – all these techniques I’ve never seen and then I’d go read about it and work it out myself. So if that’s the way I learned I’d like other people to learn that way too. So creating that content online that’s going to be really accessible for people to go and do that themselves is going to have to be a large part of what I do as well.”

By this point Tom Athron has joined, and there is a period where the pair of them are introduced, and huddle together. I have a moment to consider the pair: the latest star in the world of cooking, and the CEO of a business which began in 1707. But I find that the two of them seem to fit in some way: that’s because Brin clearly has such respect for people and is so hungry to learn – and because Athron, as I shall discover when he sits down, is bent on driving Fortnum & Mason forwards towards the future.

Athron is immediately kind about Brin – and explains how right it is that they should be sitting next to one another. “When I joined – and my predecessor actually did the same thing – we’d been asking ourselves as a business some existential questions about what we want to be, what we want to stand for, and who we are. Over the last ten years or so, we’ve become less of a department store, and more of a business which sells extraordinary food and drink.”

For Athron, having Brin here is a moment to reflect on that journey: “Ten years ago, no one would have thought to bring a MasterChef winner into Fortnum’s. And yet now it seems an obvious place to spend a bit of time – whether it’s cooking in the food and drinks studio, or having lunch in our boardroom.” He gestures at the surrounding floor, as if to gauge the extent of the change.

“This whole floor used to be menswear,” Athron says. “But in our quest to become a food business, and to become famous for extraordinary food and drink, our thinking was that that menswear was probably a category of products as a retailer that’s too far out from that particular core. So it’s not that I want everything here to be food, but it needs to be sort of connected within concentric circles. And it just felt to me that menswear was a sort of a circle too far out.”

Once this decision was taken, Athron had 1000 square feet to play with, and had to decide what to do with it. “We had to think not so much as a retailer, but more as a brand-owner and content producer. We needed a space that was going to allow us to showcase our talents – and the talents of chefs around the country. We have 100 chefs who work in this building – but they’re all secreted away behind the walls in the kitchens, and nobody sees the mastery and the craftmanship which goes into making the food.”

So Athron is a MasterChef fan? “It is such a watchable, brilliant show,” he enthuses. “That’s because what you’re seeing is what used to happen behind closed doors. You never really saw the skill that goes into it. So what we wanted to do was create a space that allowed us to show off our mastery a bit and show off our craftsmanship. So again, I was just talking to Brin saying that, that this food and drink studio is glassed off, and that counter over there behind the pillar is actually a chilled top, which is brilliant for pastry work.

The idea is that if you’re a customer walking around in the morning, you probably will see chefs from the tea salon prepping food for that day on that counter. They might be making Scotch eggs or macaroons – and just showing customers a bit of the work that goes on here. a lot of the food that they buy here is actually made in Piccadilly – it’s not just brought in.”

The rise of online shopping, and of Amazon in particular, has taught many shops that they need to be offering experiences which sets them apart. “Our customers are looking for a bit of theatre,” Athron says. “Retailers don’t just exist to sell product. They exist to provide experiences. In here, we have our “Conversations With” series, and we’ll have 50 or so people in here in conversation about, say, Borough Market, and why that started and why tinned fish is the most incredible products that we should be all eating more of. We can do book launches, masterclasses, supper clubs, all sorts of things. It’s just brought the whole floor to life.”

Fortnum & Mason was founded in 1707 when Queen Anne was on the throne – and I wonder what it is she’d recognise about the business if she were permitted to walk through London today? “William Fortnum was a footman to the Queen, and he asked for permission to take the candles that had been melted down in St. James’s Palace, and took the wax away to reconstitute them as new candles – and he sold them on this very spot. And so we still sell candles to this day, largely as a nod to that, even though candles are probably a step away from food although I can actually make quite a strong connection to it.”

I ask Athron about this and he says: “One of the things that we do in the Food and Drinks studio, for example, is a masterclass on how to dress a table for Christmas. I’m interested in those concentric circles that sit around food. We want to make Fortnum’s joyous and I think food really lends itself to that. We are a luxury business, and aim to be at the pinnacle of food and drink – but I don’t think of luxury in the same way as Bond Street thinks about luxury.

We’re not exclusive: we’re warm and welcoming and friendly and inclusive. Quite soon after I joined, we had a chef down from Cumbria whose first course was this chicken wing. And it was a Korean chicken wing, and we had 100 people on the ground floor all eating chicken with their fingers – it was the world’s best chicken wing, but it was also just a chicken wing.”

Many customers at Fortnum & Mason love the packaging but Athron realises that what the packaging contains must make good on the promise of how the brand’s produce is presented: “We’re not a packaging business. We’re a food business and the most important thing to me is that the food justifies the label. And I would never want us to get into a situation where the label justifies the food.

When I joined, we brought in a new commercial director who’s responsible for all our buying and merchandising. I sent him a hamper to say: ‘Welcome to the job’. I thought I was going to get a thank you letter but actually he wrote to me to say the shortbread was overbaked. I remember thinking: ‘That’s exactly why you’re coming’. The food has to stand up to scrutiny.”

This new attitude to the business has enabled Athron to think creatively about where the brand is seen. We’ve got three shops in London in addition to the Piccadilly store: there’s one at Terminal Five at Heathrow, one of St Pancras and one at the Royal Exchange in the city. But we want to give people access to the Fortnum’s brand outside London. The online business is one way of doing that: another way of doing it is to show up in slightly unexpected places. So you might think that you know we should be at Glyndebourne or Ascot – and actually we are at Ascot. But we also like turning up at Glastonbury.”

Last summer, Fortnum & Mason did a pop-up in Watergate Bay in Cornwall. “We had this beautiful beach house, beautifully decked out with lots of things that you can buy – picnic equipment and rugs and all sorts of accessories. But in August, there was a storm and in conjunction with the high tide, it all got washed away.

We thought: ‘What are we going to do? Maybe we should just come back to London?’ But then we thought: ‘No. This is what a British beach holiday is like. What you do is you rebuild and then you sit there in the rain’. And we did. And actually, the weather was so good in September and October that we ended up extending the season. It was the best thing we ever did.”

During Athron’s tenure, the business has pivoted towards 70 per cent on the domestic side – a trend which, Athron says, was already in evidence before he came into the job. “Ten years ago, it was about 70 per cent international customers and 30 per cent domestic, although it depends a bit on the time of year: in the summer we tend to be much more international because it’s a big tourist influx into London, but at Christmas we’re much more domestic.

But we need to appeal to a domestic audience and if you do that, the international customers will come anyway. If I position to foreigners as a tourist brand, no one from Britain will ever want to come here; I want it to be the other way around.”

So what are the career paths for young people, looking to work at Fortnum’s? “You can you start in one of our restaurants or one of our shops. In fact, most people do that. My view is that the very best retailers in the country are typically those people who started stacking shelves. Providing careers to those sorts of people is hugely important. So you can start in the shop, or you can start in our cocktail bar.”

But there are office jobs as well. “There are lots of ways into the industry: buying and merchandising is a really good way and we have a lot of young people who want to get into social media marketing and actually we tend to find young people to do that for us because they are much more savvy about what works and what doesn’t work.”

Athron enjoys walking through the store in order to see how things are working: “We’re a small business and so we’re lucky in that respect. So you can definitely spot talent, and you can sort of move them through move them through the business. There’s a lot of what my dad used to call management by wandering about: in retailing and in restaurants you have to do that. If you do that, you spot mirrors that aren’t straight or shelves that are empty.”

So how does Athron manage his time as CEO? “It’s a constant juggle,” he says. “This is my first role as a CEO though I’ve been on an interim basis before but previously I’ve been a finance director. I was the CFO at Waitrose for many years and, and I knew what I needed to do and what I needed to spend my time on: it was quite defined.

Even though, as a CFO, you have a view across the whole business, my output was defined. The great thing about finance is that it works in a set rhythm, and you know what you need to be doing at any particular time of the year. With the CEO role, it’s different because you can apply yourself in any area, and so I have to make sure I’m giving equal airtime to the whole business, and not just gravitating towards the sparkly fun bits.”

It sounds rather similar to what one sees in politics when the Chancellor of the Exchequer becomes Prime Minister. “I do find that I go from a budget meeting into a meeting about what the summer campaign is going to look like, and into an ice cream tasting. And then back to what we’re going to do with the apprenticeship levy: each day is incredibly varied.”

Coming from the CFO side also means that Athron has to, in his own words, not to be too technocratic: “I’m married to an artist, who is creative and chaotic. So I spend quite a lot of time thinking about not trying to tidy everything up, but trying to give room for people to express themselves: that’s incredibly important in a business like this.”

Would Athron ever participate in MasterChef? “I wouldn’t! I watch it and of course I do what everyone does, which is to become an armchair expert, and say: ‘Well that’s never going to work, is it? Ultimately what Brin does is a creative endeavour, I think. When I cook, I follow a recipe and it’s a logical endeavour. And what will the future hold for Brin? “I’m self-taught and so I’ve still got gaps in my knowledge. I just want to continue to learn in years to come.

I need to make sure I’m I’ve learned enough and mature enough. If I start a restaurant, I want it to be the best. Now’s not the right time.” But happily, it is the right time for lunch – and I am pleased to see Tom and Brin head off for discussions which I suspect will prove fruitful for both of them. They certainly look like they have much to discuss – and more than that perhaps, work to do together.