Kate Bright, CEO and founder of UMBRA International, spent the first 15 years of her career working in the private office sphere. During this time she worked for three international families, with varying degrees of needs for security. After rising through the ranks she became Chief of Staff in charge of the families’ operational, lifestyle and security functions, from the supply network through to the recruitment of all members of the household and security staff.

Bright decided to do her Close Protection bodyguard training in order to understand the role’s function better. Bright found that she stood out, not just as a woman but also because she did not come from a military background. “I then started to look around, network, and connected with other women in the industry, and the seedling of the idea for the business started,” she tells me.

Bright launched the business in 2015 with the goal of “focusing on doing security differently, making it more accessible, more lifestyle-oriented, hence our phrase ‘Secure Lifestyle’ was born.” When I ask about the different roles for women in security, she counters with “everyone can do all aspects of security, man or woman. It’s also not the preserve of rich and famous people. We’re trying to make it accessible to all, to create clear pathways to not just protective services, but corporate security and all the different angles, particularly cybersecurity. I advise young women and people from non military backgrounds that want to get into security to get onto a pathway like the government’s new initiative, the UK National Cyber Task Force for example. It would make me very proud for one of my young nieces and their friends to consider this as a legitimate career path in the future.”

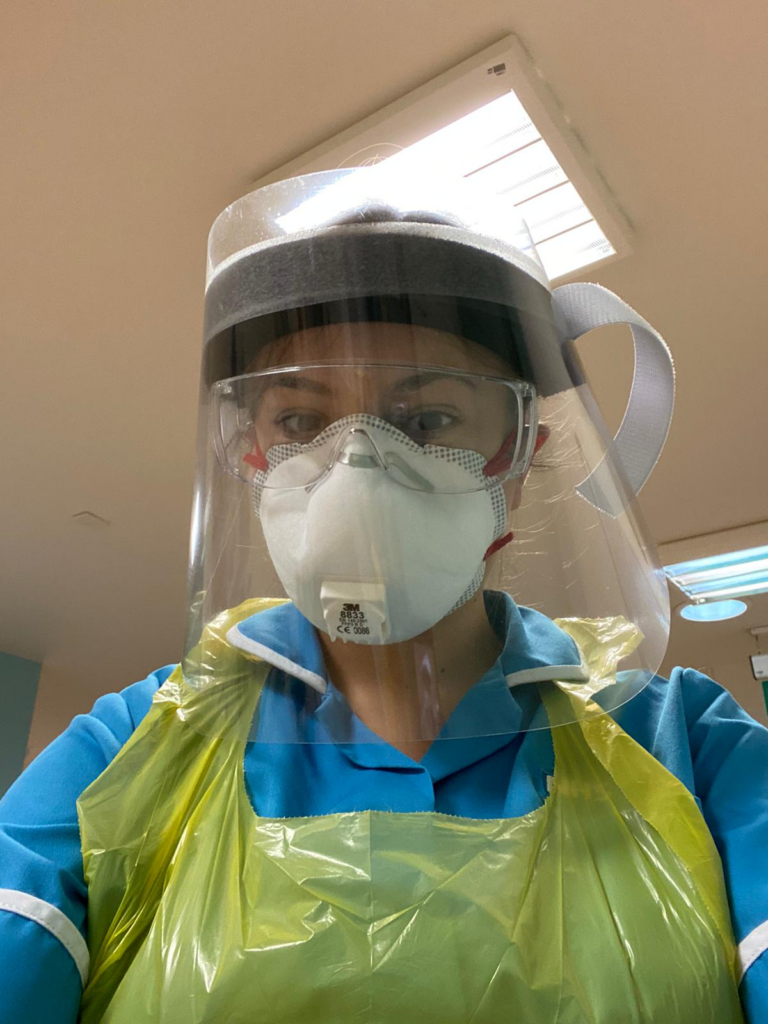

There is currently more demand for women in security than there is supply. “I’m always trying to encourage particularly my former PA community to do the training because I think it’s really useful and very important for us all to have a sense of safety and security.” It was from directly experiencing individuals from former professional sporting backgrounds such as rugby in her private office career that UMBRA now has partnerships with Saracens and Harlequins and the Welsh Rugby Players Association to encourage ex-elite sports men and women to move into the security industry. “It’s a great transition coming from a teamwork disciplined structure into a similar environment,” Bright explains. “We’ve had a lot of success in particular with women’s rugby, even despite the pandemic.”

Bright’s clients come from various parts of the world, are different ages and from different cultures. “What I noticed when I was working operationally was that ‘invisible security’ is supremely useful, and I was asked to do a TEDx talk about it in 2018.” Invisible security is the idea that protection can be discreet and able to maintain a low profile for clients. Some clients may be the super wealthy, but have no public-facing profile and others are instantly recognisable but do not wish to draw attention to themselves. “As my mother used to say: every lid has a pot. Lady Gaga would need a completely different set up, protocol and team composition to go unnoticed compared to somebody who may feature on a Sunday Times Rich List, but who may not be a household name.”

Invisible security also encapsulates digital and cyber safety as well. “The invisible threats that you can encounter online are just as important to counter in a very discreet way,” Bright explains. “UMBRA doesn’t just help clients with their physical safety – we’re also taking into consideration the whole lifestyle online and offline, because one risk will affect the other.”

UMBRA works in partnership with trusts, law firms and fiduciary advisories, to help families to achieve what Bright describes as a ‘secure lifestyle’. “Clients and their advisors come to us either proactively or reactively with problems, increasingly before they happen, or problems as they’re evolving.” This can include everything from home security upgrades through to protective or intelligence-based projects. “There’s a lot of psychology involved. It’s a lot about the feeling of safety. Insecurities, as well as securities, things that are going on in someone’s life, big litigations or disputes. House and family disruptions can cause a lot of security considerations by causing a rupture in the norm.”

Indeed, UMBRA also helps clients while they navigate difficult situations such as a private or company court hearing that is in the public interest. This can involve working with reputation lawyers and dealing with press intrusion. “The sudden shining of a light on someone is not something that I would wish on my worst enemy, it has implications that are far reaching.” Another area is divorce: “When a family separates, the two different structures that are created as a result is a big area of work,” Bright explains.

Another consideration in Bright’s “blended approach” to creating a secure lifestyle is the idea of hyper-personalised security. As clients return to travel again despite the difficulties of the Covid-19 landscape, UMBRA has received a lot of requests for people to be travelling with either someone that’s security-trained, or just someone to provide an extra pair of hands and set of eyes, such as chaperones, particularly for younger family members. Yet Bright emphasises that she wants to avoid “the ‘gilded cage’ where there is too much protection which she believes “ultimately takes away and disempowers the understanding of what it is to be safe.”

I’m interested in the technology angle, particularly the role of social media, having read about sensational heists that have taken place after a traceable social media post. Bright answers that she always keeps abreast of crime trends including burglary tourism, where people post where they’re going on holiday then organised crimes gangs easily locate them.

“Particularly in the last five years it’s been a very experimental time, a very interesting time for digital and online risk to be emerging. Certainly clients are more interested and more willing to understand how to protect themselves online.” UMBRA’s approach is to always be proactive. “It’s less stressful, it’s less expensive, much more process-driven, and incorporates protocol. It’s a very good approach, particularly for those that are coming to security for the first time, whether they’ve come into a large amount of money suddenly, eg through the sale of a company, or a valuation such as a Unicorn founder, and therefore come into some sort of fame or profile in a relatively short space of time.”

Bright also holds a number of prestigious non-executive committee roles such as sitting on the board of the Security Industry Authority, the wider security industry regulator, as well as in the charitable sector as a trustee of the Worshipful Company of Security Professional Charitable Trust. She is a keen military charity supporter, as an Ambassador of both Supporting Wounded Veterans and Veterans Aid. Last year she was invited to join the Gender Advisory Council for the British Army. “It’s actually really parallel, the security industry and the British Army,” Bright explains. “There is 10% representation across both for women and in both you’re looking at ways to create opportunities for women within their roles, and look at issues they face as well as encouraging the next generation and pipeline for the future, to give young women role models and a career path to aspire to.”

Bright adds that she’s always looking at“how to create safe spaces, particularly for women, who so often are victims of gender-based violence and crime worldwide, so they can feel safe – for example at night or, travelling around.” This has never been so at the forefront, after the tragic case of Sarah Everard’s abduction and murder. “Women have this duality of at once our invisibility being our strength, but also, we need to speak more about where we need to be counted, and that we are not just small men.”

“Both myself personally and the UMBRA business are trying to have positive conversations, and realise I’ve got ‘first’ syndrome, in being the first to do, or vocalise new ways of working and approaching big problems. It can sometimes feel like we’re having conversations that we just shouldn’t be having in 2021. But I’m more than happy to keep having them. If I leave behind a slightly more empowered and safer world, that will be a good job done.”