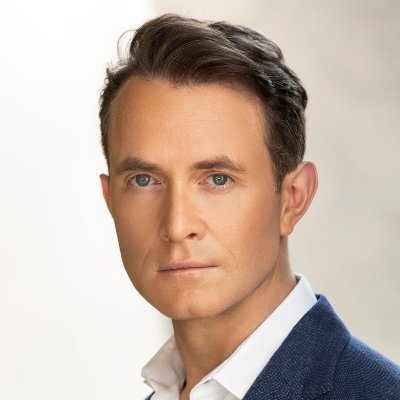

When the investigator Jeff Katz died suddenly in December 2020 it was a shock to all of us at Finito. In this tribute, friends and colleagues remember a classy, kind and remarkable man.

Jody Freshwater, Director of Corporate Investigations at Bishop Group

“Let’s give ‘em a call.” A common refrain that would emanate from our office, overlooking Pall Mall, when a case had reached a dead end and we needed a new line of enquiry. Who we needed to speak to was dictated by the matter at hand, but for Jeff Katz the late Chief Executive of the investigations firm Bishop International the answer would always be found from a conversation, speaking to someone new and sharing ideas.

Having worked in various investigative guises over the last 15 years, in the public and private sector, I have come across a number of different types of investigator. Jeff definitely fell into the category of an investigator who delivered results and broke cases open through sheer will and determination, coupled with a sharp intellect and his enduring interest in the human condition.

Born in the Bronx, New York in 1946, the son of first- and second-generation immigrants Max and Mollie Katz, and older brother to David, Jeff was fiercely proud of the city of his birth and the path he forged which led him to his adoptive home of London. He spent his childhood and adolescence immersed in the written word, often retreating to his personal oasis of the Cloisters in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where he found time and space to transport himself to the worlds of Twain, Steinbeck and Beckett.

That passion for reading and writing, along with an inherited strong work ethic, meant he was a high academic achiever and quickly found his first love, journalism, at school. As co-editors of the school magazine, he and his friend would catch the train at night and venture down to the paper’s printers in Greenwich Village, a coming-of-age adventure that opened their eyes to a world that existed beyond the Bronx.

It would surely have been beyond Jeff’s expectations at the time to realistically think that his own journey would involve the crossing of continents, meeting characters that could have come out of one of his books and being involved in seminal cases that attracted worldwide attention, all during the emergence of a new industry: corporate investigations.

Jeff was drafted into the US Air Force in ‘66, moving into the world of intelligence when he was assigned to RAF Chicksands, near Bedford in England in 1969. Enjoying how far his US dollars, and most likely his US accent, took him in the London of the 1970s, he decided to stay and pursued a career in journalism (interspersed with a first class degree in English Literature), working at the first incarnation of Time Out, followed by a punchy regional paper in Bedfordshire and finally freelancing for Fleet Street up to the mid-1980s. It was around then he met Frances, the love of his life and his partner of 40 years. Despite coming from very different backgrounds, they made a formidable team, with a shared love of literature and the theatre.

It was in 1987 that Jeff came across his true professional calling, the evolving sector of corporate investigations, and joined Jules Kroll’s eponymous Kroll Associates. Key to the company’s success in establishing the London office, Jeff was tasked with recruiting a network of investigators and sources across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East to facilitate complex cross border investigations. That legacy remains, with a number of colleagues that Jeff found and nurtured still shaping the industry today in their respective parts of the globe.

In 1999, Jeff joined Bishop International as Chief Executive and set about reshaping the company, bringing in investigators from a diverse range of backgrounds including the Serious Fraud Office. From conducting due diligence for M&A, to obtaining evidence for litigation disputes; from forensic work on homicides, to tracing misappropriated assets, Jeff became known for an ethical approach and moral compass which are now impressed into the company’s DNA. His legacy we will continue – as the following tributes will show.

Vivien Leyland, Author and Journalist

I first met Jeff in 1979 when we worked together on the provincial newspaper Bedfordshire on Sunday. The pressure at the paper was intense and it prided itself on old-fashioned scoops. We only published exclusives at that time, between 1979-85, no matter how small the piece. If another local paper ran a story that we’d been working on, we’d spike ours.

The paper built a reputation for fighting local government on behalf of individuals; highlighting official inconsistences and exposing hypocrisy and corruption, an experience which took us all into bizarre and occasionally dangerous situations, rarely encountered in local journalism. We won national recognition for the strength of our reporting; we fed numerous stories to Private Eye‘s ‘Rotton Boroughs’ column and it was an unusual week when Fleet Street (as it still was) didn’t run at least one of our pieces the following week.

His sympathetic manner and kindness made him the natural and difficult choice for breaking intimate and personal bad news stories

VIVIEN LAYLAND

Though we were a weekly Sunday paper, virtually all our news reporting took place on Fridays, when we’d start at 8am and work through till the paper was rolled off the presses at midnight. This last-minute pressure suited Jeff and also enabled him to concentrate on his own artistic pursuits.

There were just four journalists at the time and we all did everything – from proof-reading, headlines and coroners inquests to ad features, though Jeff held fierce control of the paper’s photography and anything to do with the arts (so he got to review the plays, read the books, tour the exhibitions, and interview any visiting literary figures).

His sympathetic manner and kindness made him the natural and difficult choice for breaking intimate and personal bad news stories. He was the reporter used for the ‘death knocks’, and though I covered all the county inquests, he was the one sent out for photographs of survivors and victims.

Jeff and I lost touch briefly – around 1986 – when I went off to write novels and Jeff took on the editorship of a newspaper in Portsmouth. But he wasn’t very happy there, and a year or so later, he had moved on to new pastures in corporate investigations. Working for Kroll Associates in Mayfair, he joined an emerging, exciting new industry and found a calling that he followed for the rest of his life.

Graham Robinson

Jeff and my paths first crossed when I was a junior investigator at Kroll and he was their UK country head. Although we never met at that time my name must have stuck in his memory because, after I returned to practice as a solicitor, one day he rang me out of the blue and offered me a job. He said “We have just bought this little IP investigations company on the south coast – would you be interested in working there?” I started clearing my desk at the law firm before the call ended.

We ate with Paul Lever at Rules and Jeff’s first love in life immediately became apparent to me – dessert.

GRAHAM ROBINSON

I then met Jeff in what were to become very familiar circumstances – over lunch. We ate with Paul Lever at Rules and Jeff’s first love in life immediately became apparent to me – dessert. With the possible exception of Frances I am not sure Jeff ever looked upon anyone or anything with as much fondness as he did a well-made tarte tatin. I cannot recall ever attending a client meeting with Jeff before or after which he did not find a local restaurant or café to indulge his passion.

Paul Lever, Chairman of the Bishop Group

In 1997 I was appointed by the then Home Secretary, Jack Straw, to be his representative on the Boards of the National Criminal Intelligence Service and the National Crime Squad. With the approval of the Home Office, I subsequently became Chairman of Bishop Group, a business specialising in private investigations. My first task was to find a Chief Executive and I appointed Jeff Katz who had a wealth of experience in this field both in the UK and the US. Katz revived Bishop by recruiting from the Serious Fraud Office and the Serious Organised Crime Agency, as well as taking on intellectual property experts. We worked together for 20 years in a partnership which became a close friendship. Jeff was a voracious reader, extremely knowledgeable about developments in the US as well as the UK and a talented journalist manqué. Two of his most remarkable characteristics were that he was both extremely tenacious and loyal. When his friend Robert Levinson, a former FBI agent and sometime CIA contractor, disappeared off the coast of Iran in 2007, Jeff made many attempts to elicit information from inside Iran on behalf of the family and lobbied at the highest levels in the US to find out what had happened. Despite these and official US efforts Levinson was never traced. He greeted the news that the US government stated that it believed Levinson was dead with great sadness.

Richard Alden, businessman, and client of Jeff Katz

In June 2016, on a date I will never forget, I travelled from Mexico City where I was working to Nairobi, Kenya, where I had previously been working for over three years. I was on a quick mission to move into a holiday home I had bought there to maintain a connection with a country that had become important to me and my family. I expected an uneventful visit but fate conspired cruelly to change that in a shocking manner. By midday on the day I arrived a friend of mine was tragically dead from a single gunshot wound in unexplained circumstances and I was quickly imprisoned and charged with her murder. Any tough business situation I had experienced until that time paled with the challenges I now faced.

My friend had died in my house and my gun was involved. There was no reason to believe she committed suicide so some logic dictated that another person in the house must have killed her despite the fact that there was no forensic evidence to suggest this or any motive. Apart from myself there were two domestic workers in the house but they did not know my friend. I had taken her to hospital after finding her. So suspicion fell on me. And, despite my grief, I was also baffled as to what had happened. I had been in another room at the time I heard the gunshot and to complicate matters the gunshot entry point was at an angle that was neither consistent with suicide nor murder.

In the anguish and pain that followed I was introduced to Jeff by an old schoolfriend of mine who thought he might be able to help me piece together what had actually happened that fateful day. On bail for murder I wasn’t permitted to travel so our meetings were telephonic. My lawyers were not particularly interested in theories as to what had caused the death of my friend, pointing out that it was the job of the state to prove that I had killed her rather than my job to prove what had actually happened. But the justice system in Kenya is slow and a legal process can be initiated on pure circumstantial evidence. Even if the accused is eventually found not guilty it can tie them up for years and I knew I was not guilty. I felt that I had to know what had actually happened that day and Jeff was convinced that he could help me unravel the facts using forensic science.

I wasn’t a large corporate client; my fees weren’t relevant for him but he had really gone out of his way to help me in my darkest hours and I think that speaks realms about the person that Jeff was and always will be for me.

RICHARD ALDEN

This is where the remarkable side of Jeff stepped in. Our conversations were taking place many months after the incident and almost all forensic evidence that could have existed had disappeared. I was actually sceptical as to what we might be able to achieve. But he was compassionate and unrelenting in his desire to help, probing the few facts that we knew and pushing me when I had my frequent doubts. Through his wide-ranging contacts, he engaged one of the best ballistics’ experts in the field and thereafter began a voyage of discovery, scientific simulation, measurement and theory testing that I never imagined would be possible. The result of many months of work led to one scientifically provable hypothesis – that my friend had fired the gun at the ground, probably accidentally, the bullet had ricocheted and entered her body at the strange angle that was noted, sadly killing her instantly. Jeff and his team had proven forensically that the death was a tragic accident and that no other person had been involved.

The meticulous quality of the report that Jeff commissioned persuaded the Kenyan Police to reopen their investigations and they were able to rapidly ascertain that I had not been in the same room (something that was overlooked in the initial haste to charge) and, as a result, the case was withdrawn. It’s a powerful thing to know that Jeff´s efforts directly resolved what was already a terrible situation for me and my family and one that had every possibility of lasting for a very long time with an uncertain outcome.

At last at liberty I had the pleasure of a long lunch with Jeff in London. We spent hours swapping stories. I was particularly interested in his work around the death of Roberto Calvi, my first work experience having been working on the liquidation of Calvi´s bank following his death. I was struck by how interesting a career he had but also by his human element. I wasn’t a large corporate client; my fees weren’t relevant for him but he had really gone out of his way to help me in my darkest hours and I think that speaks realms about the person that Jeff was and always will be for me.

Dr Angela Gallop CBE

In1992, Jeff contacted me to ask if I would review the original forensic science investigation into the death of Roberto Calvi – the Italian banker who had been found hanging from scaffolding beneath Blackfriars Bridge in London ten years earlier, and conduct any further tests which might help answer the central question of whether Calvi had committed suicide or been murdered.

There had been two inquests – the first had recorded a verdict of suicide, and the second, an open verdict. But this was not good enough for Calvi’s family who knew that, as a devout Catholic, the last thing he’d ever think of doing would be to commit suicide. Jeff had been hired by the family to re-investigate Calvi’s death and, by the time I joined his team, he was already a mine of information about the case.

I accepted the job immediately as it seemed a very interesting project, but when I realised how little forensic work had been done at the time, and how few items were available for testing, I began to wonder if I’d bitten off more than I could chew. But right from the outset, Jeff was tremendously supportive.

It wasn’t long before I’d become thoroughly familiar with the foreshore underneath Blackfriars Bridge, the scaffolding from which Calvi had been suspended, and the rope and stones involved. And, with a forensic chemist colleague, I had established a testing strategy which would hopefully be able to gradually remove possible options, leaving us with an inescapable conclusion. And Jeff helped every step of the way – by arranging a boat trip down the river at night – from Greenwich to Blackfriars, so we could check timings and see what it would have been like under Blackfriars Bridge on the night in question, and what would, and would not have been possible with a boat. We went to Milan so I could inspect the rest of the clothing Calvi had been wearing at the time – it had been returned to Italy along with the other possessions he’d brought to London on the fateful trip. Jeff supplied me with other, similar items of Calvi’s clothing and some gravel from Calvi’s driveway at home, and he got hold of some of the original scaffolding so that I could use all this for my tests, he had me crawling all over a dilapidated boat looking for green paint that matched some on Calvi’s clothes, and all the time he kept updating me on his own researches.

Then came the day that I had to pull all my findings together in a report and, with Jeff, present it to Roberto Calvi’s son, Carlo, on behalf of the rest of the family. By this time, there was, as I had hoped, one inescapable conclusion, and that was that Calvi had been murdered and had not committed suicide. This was accepted by the Italian courts and some time afterwards I found myself giving evidence at the terrorist court in Rome about all the tests we had performed and why I was convinced that Calvi had been murdered. This was to help set the scene for the trial of several of the people who had featured in Jeff’s work.

This case ensured that I used all of my scientific skills in erecting and testing hypotheses, I shall always be very grateful to him for all of this.

Oliver Maude-Roxby, colleague

Jeff’s generosity of spirit was evident at every Bishop Group Christmas party. With 20 or more employees usually present, each year he would take the time to choose a book that he thought would be of particular interest to each individual. Jeff would arrive carrying a couple of carrier bags and, at the end of lunch, hand out each individually labelled present. I know that Jeff appreciated my love for his city of birth, New York, and I recall telling him that one day I would join him there to experience the city through his eyes. But it was never to be.

Jonathan Metliss, friend

I would always call Jeff for a second opinion to discuss an idea if I needed any guidance on an issue, or simply to have a chat. He was unfailingly helpful and reliable, and a truly genuine person. I see his mobile phone number in my address book, but sadly realise that if I rang I would now get no answer.

David Glasser, friend

Jeff sometimes asked if I could advise or help on his assignments. On one occasion, he asked whether I would watch a person at a dinner reception to observe who he might converse with. I agreed without hesitation and spent the day in my guise as an interested party. There was panic at 10.15pm when I blinked and he was nowhere in sight. He was not in the toilets. When I asked the cloakroom attendant if ‘my friend’ had just left, he confirmed he had. Thankfully the doorman confirmed where the taxi hailed was directed to go and I went to a famous nightclub in pursuit. I followed and reported back. My reward lunch was almost as enjoyable as my day living my dream.

Elena Egawhary, friend, colleague and mentee

The first time I met Jeff Katz he was in a three-piece suit holding court in front of an audience of enraptured investigative journalists. His slick powerpoint on the corporate investigation industry was famous as one of the highlights of the Centre for Investigative Journalism (CIJ) summer school in London. Jeff was a regular presenter and every year his session on the corporate investigation industry was standing room only. He walked everyone through the origins of the modern corporate investigation business in the UK. Being a former journalist himself, Jeff understood how investigative journalists and corporate investigators operate in very similar worlds even if they have very different aims. Five years ago I decided to embark on a PhD examining the role the corporate investigation industry plays within society by writing the history of Kroll Associates.

If he criticised it was because he believed you could do better, that you were better and he told you so.To know Jeff Katz was to be very lucky indeed.

ELENA EGAWHARY

Jeff immediately made time for me. He shared his contacts, and we would speak on an almost bi-weekly basis over the course of the next five years. He was also an honest critic of the best kind: “this sounds like an advert” he once chastised me when I let him read the draft of a paper I was working on. “You can do better”. If he criticised it was because he believed you could do better, that you were better and he told you so.To know Jeff Katz was to be very lucky indeed.

Ronel Lehmann, friend

In August last year, I asked Jeff whether he could help find one of my oldest friends from City of London School. Oddly, our Alumni Development Office had no record of him either. I provided Jeff with some scant details and his last known address in Italy. Within 24 hours, he had tracked him down. I rang Davide Malliani to tell him that had taken me appointing a Senior Corporate Investigator for us to be able to finally speak again.

I read your restaurant reviews over the weekend and, because I know you and could hear your voice in the writing, I enjoyed reading them. Having said that, I don’t think Jay Rayner has anything to fear.

RONEL LEHMANN

I had myself written some restaurant reviews which were published. Jeff wrote to me: “I read your restaurant reviews over the weekend and, because I know you and could hear your voice in the writing, I enjoyed reading them. Having said that, I don’t think Jay Rayner has anything to fear.”

I proposed Jeff as a possible guest for Desert Island Discs. I received a reply from Cathy Drysdale, Series Producer, Radio Four “We’re always pleased to receive suggestions and thank you for the enclosed cuttings. However, as we’re a very small team, you’ll only hear back from us if we wish to issue an invitation – we hope you understand.”

Jeff supported many good notable causes. He wrote to me: “As someone who benefited from the days when higher education and career advice was free, I am pleased to donate a Finito bursary in the knowledge that it will give someone an advantage they might not otherwise have.”

Jeff was excited about writing for Finito World. When his Letter from an American made the grade in the October issue, he was so encouraged that he submitted a further piece for inclusion in this issue. We received his latest article penned a few days before his death, and include his piece as part of our tribute.

Jeff teased me endlessly by saying that he liked me in spite of me being a Tory and I larked about when he proffered alternative strategies in politics, none of which would actually work.

The last time we had lunch together was a little Italian restaurant tucked away in the middle of Theatre Land. It was exquisite, home cooked Italian cuisine at its best. Jeff was so at home with Pino Ragona who lavished service, lasagne, red wine and crème caramel all over me. Jeff salivated over their delicious selection of puddings. The history of the restaurant is mounted and sealed on the walls with an abundance of photographs. I will return to Giovanni’s to ensure that he too is remembered as a loyal customer and for future generations.