Patrick Crowder

At Finito, we continue to believe that effective mentoring is the one thing which can really make a difference to someone’s life chances. One of the joys of the work the organisation does is to receive testimonials after an assignment. In these we see the numerous ways – both big and small – in which one-to-one mentoring can alter lives.

But it’s also an interesting question as to how mentors are made. What is it which inspires people to give back? And how do we at Finito make sure our service adds value to every mentee which comes through our doors?

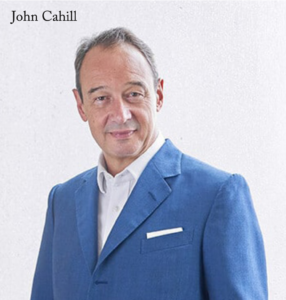

Georgina Badine has just been appointed Finito’s new Head of Admissions. She will be responsible for recruiting new mentees and guiding them through their journey towards employment and a fulfilling career. She oozes passion about her new role and is passionate about driving up student intake, and helping to manage the journeys of Finito candidates.

Badine has had a fascinating and varied career, with extensive experience in finance at Barclays, and then in business, recently setting up boutique commercial property business Treio, which recently paired with Finito World. Georgina has the knowledge and network to guide Finito mentees to success. But even before assuming the role, she had already proved herself a skilled mentor, having tutored students and adults from all walks of life in both French and English.

Ronel Lehmann, Chief Executive of Finito Education Limited, welcomed the appointment, and referred to Badine’s recent client relationship with the business: “We are fortunate that a former client of Finito was so impressed with the work that we do that she immediately wanted to join us. As with all our student and career change mentoring candidates, we always help to make things happen.”

So how did Badine become interested in mentoring? “My passion for mentorship started when I was in school,” Badine recalls. “I was a member of the National Honor Society and, within that, you would be expected to mentor and tutor other students. I got involved and I saw that I really enjoyed it, and then I started helping my friends and children of friends with different issues.”

It is this passion which marks out a mentor: very often Finito mentors will have been doing their own mentoring, sometimes as a kind of private volunteering, before they join us. Recent testimonials show that Badine’s mentoring can be truly transformative.

One mentee, Matthias Alvarado-Schunemann, tells us: “I have been mentored by Georgina from Finito for about six months now. Having her as a mentor has helped my confidence greatly as I prepare for the next chapter of my education with university. She helped me to write a well-presented personal statement for university as well as practicing my interview skills by doing various mock sessions. Her mentoring helped me decide which course I wanted to study and how to best articulate this to the various universities I decided to apply to.”

Badine’s mentoring also has another focus: “I’m very passionate about helping people who are being bullied either at school or in the workplace, and I feel that nowadays, a lot of people might be afraid to speak up,” she continues.

Some of what drives her, then, is personal experience: “I’ve also experienced quite a lot of adversity myself being a young woman in the finance world, when the treatment of women is often not what you would hope or expect. I know that I would have benefited from having a mentor to support me and stand up for me. I think too often people stay quiet if something is happening in the workplace or at school, and I think more needs to be done to help these people.”

Badine’s new role will also involve public speaking and organising events for Finito mentees. When it comes to bolstering the Finito network and creating opportunities to learn from top-level speakers, Badine’s wheels are already turning.

“I have quite a few ideas,” she says. “For example, I’m looking to organise an event within a restaurant, as I have a few connections in the hospitality space. It’s all about getting the word out about what we’re doing and inviting the right types of people to these events,” Badine continnues. “In addition to that, I am thinking about Geneva and Paris, where I have connections – as well as the US. Finito is a unique and trail-blazing organisation and I feel now is the time, with over 60 business mentors, for it to deepen its global ambition, like its magazine Finito World.”

So what kind of events will Badine be running? “We’ll get engaging speakers to come in, and I’ll speak as well, but I’m also really interested in getting people who are being mentored to come. Candidates who are considering joining Finito will want to hear that side of things. My main plan is to organise events, meet with my network, and find the best way to spread the word about our mentorship.”

Badine is also keen to stress that everybody is welcome in the Finito family. When a candidate comes to Finito for help, often they will have an idea of what it is they would like to do. However, Badine points out that this is also not always the case, and it’s certainly not a prerequisite. “We never turn a candidate away and we never let them go until we succeed,” she says.

She also offers some closing advice for those about to enter the world of work: “It’s important to do various internships in different industries because I know what it’s like; I initially wanted to be a journalist. I was convinced that was what I wanted to do, and I did various internships, but when I found that internship in banking I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it. I saw a different side to it, and had I not done that internship I wouldn’t have realised what that side was,” Badine explains.

Badine, then, brings a profound passion for mentorship, a global outlook, and a unique network to the business. She also illustrates the need for businesses to be dynamic coming into a period which few observers of the global economy expect to be plain sailing.

But perhaps as much as any of these things, she brings compassion and empathy to her role. “It’s very difficult to know what you want to do when you’re 18, so I think getting different experiences is very important,” she explains. “I would also say that it’s not just about the firm you’re going to work for, it’s who you’re going to work for. Look at not just what you want to do, but who you want to learn from. It should be someone who inspires you, because having a good boss is very important.”

https://www.finito.org.uk/management_team/georgina-badine/