Friends and family remember the great and charismatic investor and party guru Terence Cole who touched many lives.

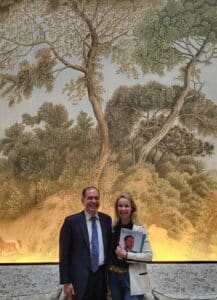

Ronel Lehmann, CEO, Finito Education

I often find myself in, and around, Marble Arch for meetings and can be seen bowing my head as a mark of respect to Terence Cole outside his Upper Berkeley Street office. It was there thanks to Liz Brewer’s introduction, that we first met.

Terence founded MARCOL with Mark Steinberg in 1976 and together they created a multi-billion international investment group. Terence was a true visionary and a creative genius. He was not afraid of sharing his politics and utter disdain for Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London, who he hated with a vengeance for destroying the road infrastructure and transport network. He was a man who understood the importance of retail customers and championed Chelsea Harbour, following its acquisition in 2003.

I remember our many conversations during the pandemic. He shared our passion for inspiring the next generation and adored our work helping young people to find meaningful careers. He loved this magazine and was responsible for coming up with an improved mentoring business strapline, The Employability Experts, for which we will always be grateful.

Before he died in December 2022, he told his staff to ensure that his mobile phone was fully charged and buried with him just in case he could make a call from the other side. Whenever I meet his colleagues, we do ask each other, “Have you heard from Terence?” He must have known that he will be remembered by us all with a smile.

He impacted many lives through his generosity of spirit and leaves an incredible legacy which his family continues, as patrons and benefactors, to many of the charities that he supported.

Mark Steinberg, co-founder and joint CEO, MARCOL

Terence and I worked together as partners for 46 years from 1976 until he passed away. There was a substantial age difference between us – about 25 years – but that never mattered. It just worked. Having faith in each other and having trust in each other was fundamental to a relationship which lasted over 40 years, longer than most people’s marriages. When a business relationship lasts that long, you know how to finish each other’s sentences, and you know what your partner is thinking. In meetings, you intuit who should take the lead. Our roles were very merged together. I tended to deal with more of the financial side – the fundraising and the debt-raising. But strategically we worked very closely.

In 1976, we bought a ten-year lease on a property – a stone’s throw from the offices we still have today. That was £10,000 and it was the start of MARCOL: the name was made up of part of my first name and part of his second name. We worked from his dining room table to begin with and then from a basement windowless room in South Audley Street. We had a part-time secretary coming in and working with us and we built the business up, literally from zero, working with The Portman Estate. We had no capital but we were tenacious. Soon we were working with other estates like Cadogan, Eton College and Grosvenor.

Over 40 plus years, MARCOL grew from nothing into quite a substantial pan-European operation that wasn’t just real estate in the latter years: we went from being a small residential real estate developer to being commercial as well. In time, it grew beyond London across the UK. We went into Europe and invested in Germany, Poland, Romania, France, the Czech Republic, Hungary. Soon we were involved also in operational businesses with real estate foundations such as hotels.

Terence was intensely private, but charismatic, a maverick, a lateral thinker. He had very strong views about how he saw things. He had very leftfield views that really added a lot of gravy and sauce to what might otherwise would have been quite straightforward. There was nothing linear about him. You’d go into a meeting with him with other people and he would come from a complete tangent, and confuse them to begin with – but by the end of it they had bought into the idea.

Terence engendered very strong loyalty from people working with him from his staff. One of his PAs worked for him for 60 years. She also passed away last year but she worked for him way before we were together in a previous life and then left him for a few years and then she came back again. He created this very professional business but which had a family kind of atmosphere. Whether it was dealing with people’s health issues or personal issues he would always be the first to say: “We are going to send them away on holiday” or “We are going to pay their medical bills or whatever it might have been.”

Mentorship was very important to him. Terence was a very good judge of character: when we were interviewing people for roles or looking at businesses, he had a kind of sixth sense about people and was able to take a view on whether we should take somebody on or not.

Of course we had our ups and downs. We have been through numerous recessions: the late 70s property crash; the 1989 property crash; Lehman Brothers; Covid. He was a real personality – a bear of a man, who loved his food and loved people, loved to entertain, and loved to investigate something new.

Claire German, CEO, Design Centre Chelsea Harbour

It was almost as if he’d been here before. It’s been strange since Terence died, not having him involved in my life. He played such a huge role ever since I arrived here 13 years ago – and I knew him before. He was this fabulous mixture of incredible business brain and great vision, who seemed able to predict what could happen. For instance, during the pandemic he said: “Darling, this is the easy bit, the pandemic. It will be post-pandemic with everyone trying to return to normal that will be the hard bit.” He was already thinking about getting people back into the office while everyone else was getting used to lockdown.

Terence had these intense business meetings where he would really put you through your paces. He would not suffer fools gladly: you had to know your stuff – bring in energy and have ideas. He had a twinkle in his eye; this made him quite mischievous. If a situation was getting out of hand, he would immediately see that and disarm it and then bring a lighter tone to it. He had great emotional intelligence.

Sometimes when Terence went off on a tangent, I would start off by thinking: ‘I’m not quite sure where this is going’. But you always had to believe in the journey because you knew the journey was a very well-thought-through one and you had to trust in that.

Every day at the Design Centre Chelsea Harbour, I can hear him in my ear. He would say: “We’ve got to stick to the concept”. He would drill that into me. The space would have to feel lively and create reasons for people to come. Right down to the food, the attention to detail was incredible. The Design Centre Chelsea Harbour is the jewel in MARCOL’s crown: they are very proud of what they achieved and rightly so and they had the vision to create this centre. It’s not just a landlord-tenant relationship: it’s bricks and mortar and beyond.

He was also the party maestro. He wasn’t particularly easy-going about it because he would be very critical if he didn’t like something. He would say that a party had to have the right atmosphere: a heartbeat.

It doesn’t quite seem real that he is not here. I keep expecting him to burst in at any moment asking for food. Food was always a big thing in the meetings. He would arrive; we would be in a meeting and he would always arrive after everyone else and say: “Darling, can you get me an egg sandwich?” I was learning at the feet of the master.

Nigel Lax, Director, MARCOL

I first met Terence in 1994. I was in my late 30s, and had been through a fairly institutional career. I qualified as a chartered surveyor, and spent 10 years in private practice post-qualification in various parts of the UK. Then I came down to London to work for a developer in the late 80s. This was an inauspicious time to come to London: the developer I worked with was going down the tubes like a lot of developers at the time. I had a respite at the Halifax Building Society again very traditional financial institution – and then I met Terence.

He came into my office on the Strand. He was always a larger-than-life character and very self-confident. He said: “I believe you have got an asset in Docklands that you are trying to sell for the Halifax. I would like to buy it.” We weren’t even marketing it at the time. Cutting a very long story short we negotiated a sale of this asset over a period of no more than probably 3 or 4 weeks. I didn’t know MARCOL from a hole in the wall. It was before the internet so you couldn’t check anybody out. There then ensued a long torturous negotiation with Terence in the Churchill Hotel where he would turn up two hours later than scheduled.

After that he made me a job offer. I realised I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life at the Halifax. 30 years later I am effectively still working for the Cole family office and for Mark’s family office: it’s gone in a flash. Terence took you outside your comfort zone beyond the boundaries that you were comfortable with.

That’s the best thing you can do in your career: to be tested all the time is to learn all the time. Now, in my late 60s, I am still looking for new intellectual stimulation. I have also developed other interests which I don’t think I would be doing but for Terence: he was so mind-expanding in the way he approached things.

Nobody was a better litigator than Terence: he loved a fight. If he thought somebody was trying to get one over on him he would be tenacious. I remember we were suing a firm of valuers, a matter which gone on for probably two and a half years before Terence really got involved. We were getting to the final stretch in negotiations with the valuers’ insurers. On a Friday afternoon, we got them up to a plausible number but Terence wasn’t impressed. In meetings, he never had notes. He never wrote anything down. In this one, he got up and walked out and said: “When you see sense come back and talk to us but we are not accepting that offer.” He just walked out and nobody knew what to say. That was the end of the meeting. During the course of the weekend he got them to go up another 10 per cent on where they were on Friday afternoon. He rang me on the Tuesday and asked what I thought. I said: “I’d have been happy to take the number they offered us on Friday but clearly you have done a much better job than I’ve done.” He replied: “I’m only doing it for you.”

He also had this extraordinary attention to detail. My wife worked with him on one of his refurbishments which was hugely frustrating for her but she learned a huge amount. Specifically, don’t put up with second best if you know it can be done better: particularly if you are paying for something, criticise it. My wife is very like him now. We are doing a project up in Yorkshire and for the contractors it’s frustrating at first, but if they get it, people can lift their game.

Parties were Terence’s hobby: that was what he lived for. The Coles always used to throw a party on Boxing Day. On one occasion they took a suite in the Savoy but we turned up at the allotted time and were held on the ground floor in the lobby of the hotel because the room wasn’t ready. We then discovered that 30 minutes before the party was due to start, Terence had decided he didn’t like the layout of the room so he literally got them to take the doors off the hinges so that the space flowed better.

It was certainly never dull. MARCOL isn’t the same without him. There are youngsters in the office who will never experience that. With Terence there were no airs and graces: no aloofness. He wanted to be looked after and respected by people but at the same time he would give that respect and care back.

Victoria Boxall-Hunt, Group Operations Director, MARCOL

I shall never forget the first day I met Terence. He made me laugh so much in my interview that I snorted! It makes me go red at the thought even now – 18 years later. On my second interview, he sent his car and driver to collect me and bring me to Upper Berkeley Street to meet him and Mark. This was no ‘normal’ company and so began my journey with MARCOL, a journey that has shaped my life and given me many experiences that I would never have had. It has taught me a huge amount, introduced me to some incredible people and has tested and delighted in equal measure. There is also no doubt that we have laughed a lot and had a lot of fun over the years.

I genuinely think they broke the mould when they made Terence Cole. He didn’t do things that people expected, in fact quite the opposite. I learned a lot from him, particularly to be patient, stay quiet, listen intently and to stand up for myself and fight my corner. He had an innate understanding of people and a way of asking questions and getting things done that astounded. What seemed utterly preposterous at the beginning of a meeting would seem totally doable (somehow) by the end. He had the most incredible way of talking people into doing things and making people think it was their idea in the first place. He helped me plan my wedding and took great interest in all things. He even said I must have his car and driver to take me to the church and that he would get a taxi.

I have witnessed so many unbelievably kind and thoughtful gestures over the years that genuinely made a positive impact on peoples’ lives. He was driven by making a difference and an impact, which he did. I think of him often an ask myself regularly: “What would TC have done?”

Niki Cole, Terence’s wife

I was married to Terence for 48 years. When I met him, I was a young actress who had just done a movie in LA. I was doing publicity and was asked to go to a fabulous European men’s shop to sign autographs. I saw a big giant limousine pull up outside the shop, and Terence got out with two guys. He looked around and was soon trying on clothes. At the end of that, he said: “I’m going to take all these clothes on the condition that that lady over there delivers them to the Beverly Hills Hotel.”

When I was informed of this proposal, I said: “I’m not doing that.” But he had this power about him and this presence. I went with the driver there, and said: “The clothes are here” and I was asked in for a drink. I stayed him with a week at which point he said: “If you play your cards right, I’m willing to marry you.”

Terence knew it all – he had no lack of confidence in what to say or do in any situation. He was very relaxed and brought people down to earth, and attracted them: he brought them along.

I’ll never forget the party he threw for my son Alex and his wife after they were married. The theme was Hollywood glamour. It was at a venue outside London, with 500 guests. Every single one of them had their own chauffeur and their own car and were taken to the country. The party finished at 5am. There were different-themed rooms and all sorts of music: the Royal Opera; the Black-Eyed Peas, Shirley Bassey. My son and his wife knew nothing about it. There was a Doctor Zhivago-themed room where there were ice sculptures dispensing vodka and Russian soldiers on horseback. There was another room for period films, with ladies dressed in Jane Austen-style costume. We went downstairs and there was a sheet of raining ice, and suddenly everything went ‘Boom!’ and opened like a curtain and Alex and his wife were standing there. Jools Holland sang; José Carreras sang; breakfast was served at five in the morning.

Perhaps it could be daunting sometimes. If I said, “I’m not doing this,” he’d reply. “We are doing this – I know what’s right.” The secret to staying married to him was to know how to challenge him back.

When he died – in London at the Cleveland Clinic, I wanted him to be buried in America. It’s the most beautiful place. On one side you have the sea, on the other are mountains. He is buried in his tuxedo jacket, his pink open-neck silk shirt, white trousers and green velvet carpet slippers. My husband danced to his own tune in life.

Alex Cole, Terence’s son, founder of Elevate Entertainment

My father was a man who created his own destiny: it was his way or the high way. He was a man who’d built something from the ground up in business, and didn’t apologise for it. Why should he? He could humble any mighty person – no matter how powerful you were, he could always teach you something. He had this way of speaking in a low voice, of taming people, and drawing people into his wisdom. I knew if I went into property development and private investment, I would never get close to what he was doing: I didn’t want to interfere with the master. My path in life was a little to his chagrin: “There’s no money in that,” he’d say.

So I now produce and develop big TV shows: that’s very different to what my father did. There were things we each had to navigate in relation to each other’s choices. My father wanted me to always admire what he did, but I could never achieve what he had done in business, even though he would have liked that. For me, it would have been disrespectful to step into those shoes.

I was going to stand on my own two feet. While he was around you knew everything was going to be fine; he was going to see to that. He needed to control the family – and not in a bad way. I felt secure in my family; you knew you could always go to this wise man for help, whether it to be personal or to do with business. If you were under his watch, you were taken care of.

When he went we all felt lost: me, my mum, Mark. Because my sister had health challenges, I had pressure to keep the legacy of the Cole name going. That created a wonderful bond, but it also created a pressure. When my dad passed away I wanted to keep that security nearby, and have him close to me: I arranged to have him buried about 15 minutes away. He liked the sunshine of America: he liked getting out of England – he found the mentality to be: “You can’t do that”. My father would always say: “Well, I’m doing it anyway.”

As I proceeded with my career, he really became interested in films. He decided he wanted to tell me how to produce films. He would say I should host a talk show and so on. He was proud: it was a creative job, dealing with celebrity and a bit more glamorous than property – or at least it seems that way until you’re in this world. He would say to me quietly under his breath: “You know, I’m proud of you, right?” When he gave compliments, you knew they were valuable – more so than with people who shower you with affection and praise.

When it came to the parties, I’ve been to the Oscar’s – and they’re boring compared to what my father could produce. He planned things but never wanted to be the man of the moment when they would happen – his kick was to stand in the corner as people took the journey through the party.

When it came to work, he never had to behave in a certain way: he was the meeting. Everyone had to pause while he did his things. But the theatrics encouraged people to want to do business with him; he wasn’t conventional. And he loved everyone: the team, the staff, the doorman. If you were part of his group, you were part of his group. It created company morale. He didn’t waste his life in any way. When he died he was 90 years’ old. His mind was strong, that mind could have gone on to 105 in the office. But his body gave up on him which makes the loss of my dad harder to stomach.